Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

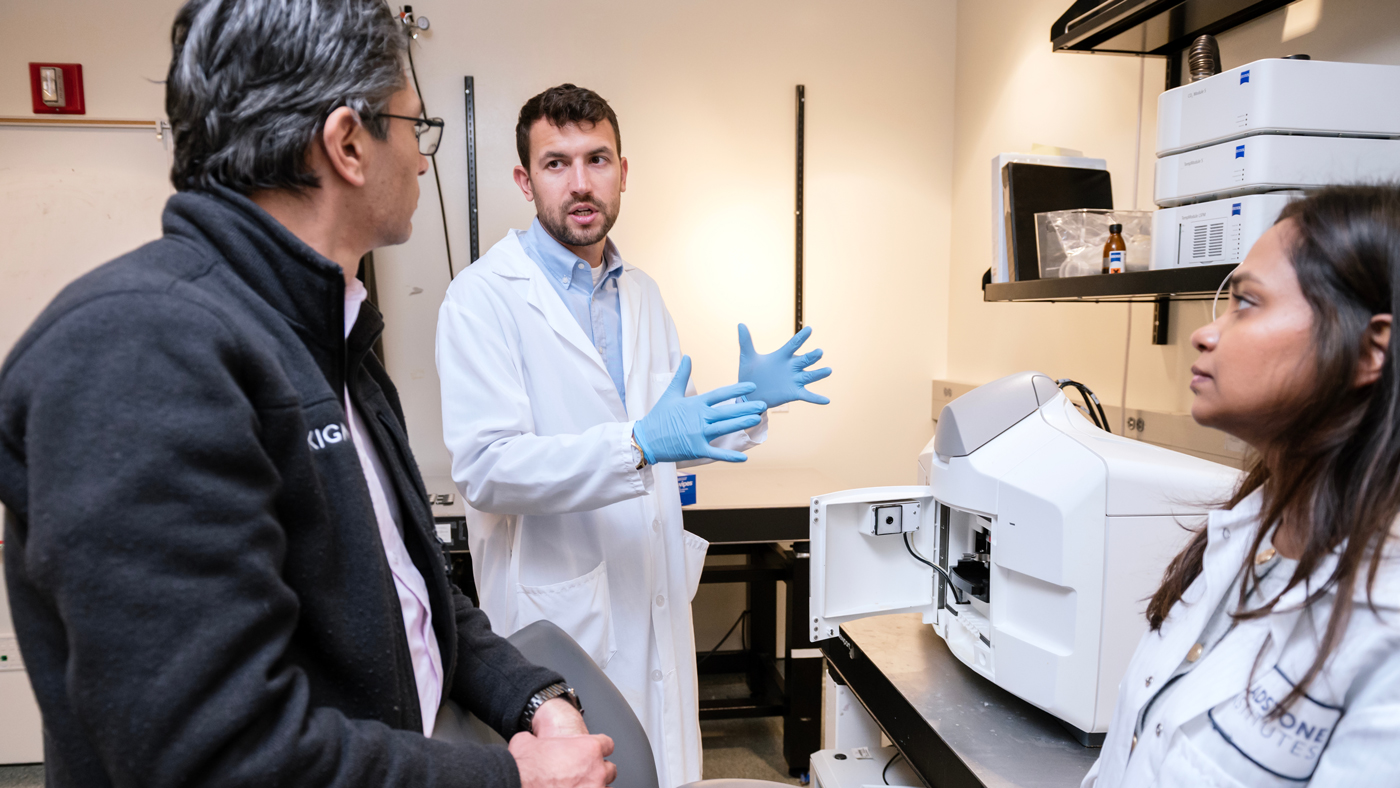

A team of scientists at Gladstone—including (from front to back) Benoit Bruneau, Jon Muncie-Vasic, Irfan Kathiriya, and Kavitha Rao—identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

Every year, nearly 40,000 U.S. babies—or about one in 100—are born with a hole in the wall between their heart’s chambers. For many of them, it can mean a lifetime of surgeries, medications, and careful monitoring.

These congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect, yet scientists have struggled to understand exactly how this critical wall of muscle, called the interventricular septum, forms during development and why it so often goes wrong.

Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco (UCSF) have discovered that a boundary between two populations of heart cells, established very early in development, acts as a crucial guide for proper heart formation. When this boundary is disrupted, cells mix inappropriately, leading to holes in the interventricular septum and other defects, according to a new study featured on the cover of the January issue of Nature Cardiovascular Research.

“We’ve uncovered a completely new mechanism for how the heart patterns itself during development,” says Benoit Bruneau, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and co-senior author of the new study. “Our study offers brand-new insight into the incredible degree of finesse required to assemble an organ like the heart.”

A group of scientists uncovered a new mechanism that explains how holes form in developing hearts, which they hope will eventually lead to new therapies for congenital heart defects. Seen here is Kavitha Rao, one of the researchers who worked on the study.

To date, scientists have identified hundreds of genes involved in heart development, but understanding exactly how each one contributes is challenging. But nearly half of all heart defects still have no known genetic cause.

“By further studying the pathways that we’ve identified here, we hope to eventually pinpoint some of those causes and identify new potential therapies,” says Irfan Kathiriya, MD, PhD, professor in the Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care at UCSF and co-senior author of the new study.

A Gene That Causes Heart Defects

One gene in particular has puzzled researchers for decades: TBX5. Mutations in this gene cause Holt-Oram Syndrome, a condition that includes holes in the interventricular septum—but no one understood why or how.

“I’ve been studying this gene for over 25 years, trying to understand how it causes heart defects,” says Bruneau, who is also William H. Younger Chair in Cardiovascular Research at Gladstone and a professor of pediatrics at UCSF. “My own daughter was born with this type of defect, so understanding these mechanisms is deeply personal to me.”

From left to right: Irfan Kathiriya, Kavitha Rao, Benoit Bruneau, and Jon Muncie-Vasic.

To solve this mystery, Bruneau teamed up with Kathiriya. They tracked cells in which the gene TBX5 was active during heart development in mice.

They expected cells with TBX5 turned on—usually found on the heart’s left side—to be separate from cells expressing another gene, MEF2C, found on the right side. Instead, they found a thin stripe of cells with both genes turned on, located at the future site of the interventricular septum, between the heart’s left and right ventricles.

“We were really surprised to see this and it made us think of a concept in developmental biology called a compartment boundary,” says Bruneau.

Maintaining Boundaries

A compartment boundary, he explains, isn’t a physical wall, but rather a population of cells with special properties that actively prevent neighboring cell populations from mixing. Few such boundaries have been discovered in mammals.

The researchers watched the doubly-marked cells in more detail over the course of development. They found that the stripe of cells appears before the heart even forms and that it maintains its shape and position as the organ develops. When they destroyed the boundary cells early in development, something striking happened.

“We saw an incredibly disorganized septum, and cells that are normally kept separate were mixing together,” says Kathiriya, who is also a visiting scientist at Gladstone. “It confirmed that these cells aren’t just sitting there; they’re actively maintaining the separation between the left and right sides of the heart.”

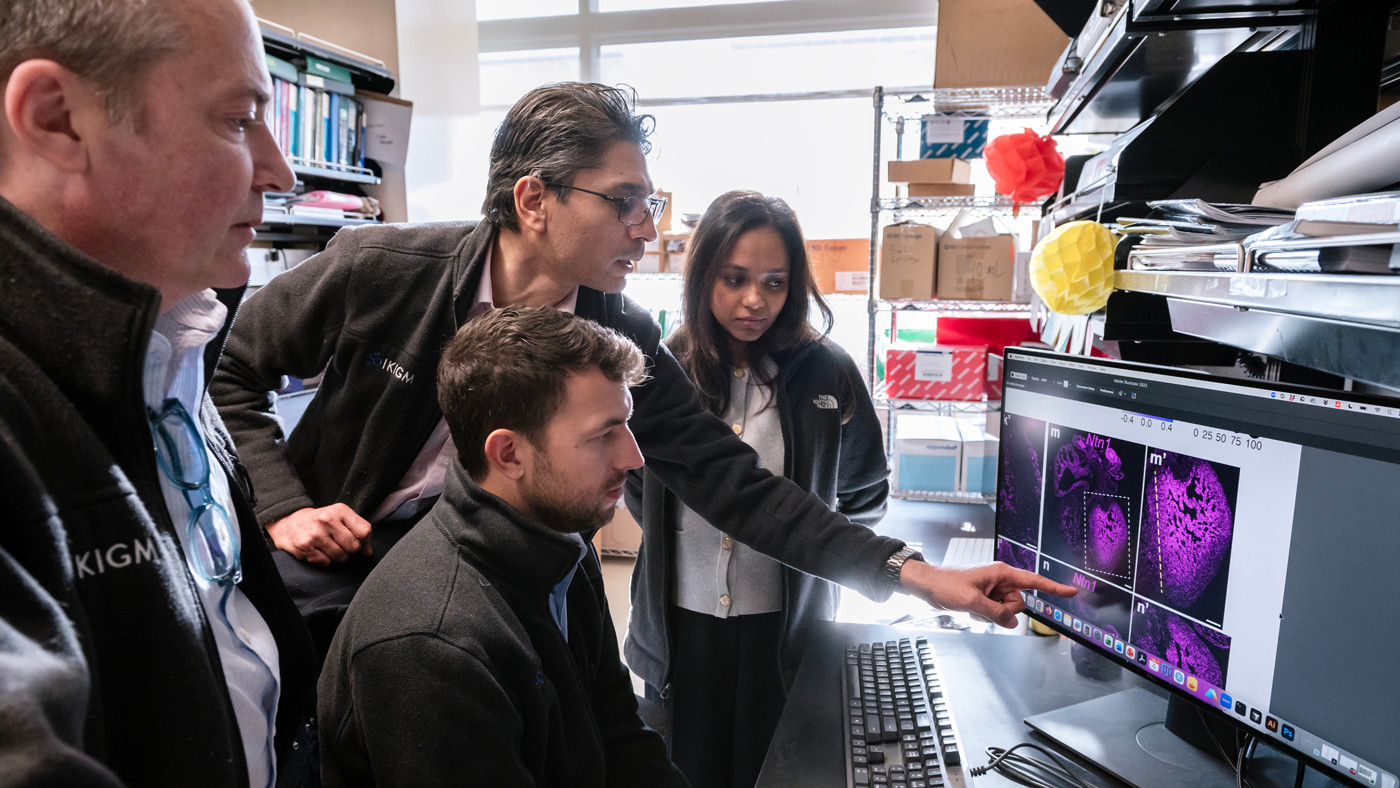

Kathiriya (left) and his colleagues, including Jon Muncie-Vasic (center) and Kavitha Rao (right), identified the gene responsible for maintaining the boundary that separates the two sides of the heart. When that boundary is formed incorrectly during development, it can lead to congenital heart defects.

Next, the team reduced levels of the TBX5 gene in developing mouse hearts, mimicking what happens in Holt-Oram Syndrome. The compartment boundary was disrupted—cells were in the wrong position, lost their organized structure, and the cells usually found on the left and right sides of the heart were mixed.

“Instead of being arranged like a Roman phalanx with shields all aligned, now the soldiers were disoriented, facing the wrong way,” Bruneau explains. “They’d lost their commander.”

The experiments confirmed that TBX5 is responsible for maintaining the boundary compartment separating the two sides of the heart.

Guidance Molecules Point the Way

TBX5 itself is a transcription factor—a type of protein that controls hundreds of other genes—making it difficult to target with drugs. So, the scientists analyzed which other genes were turned on and off in the newly identified boundary compartment cells.

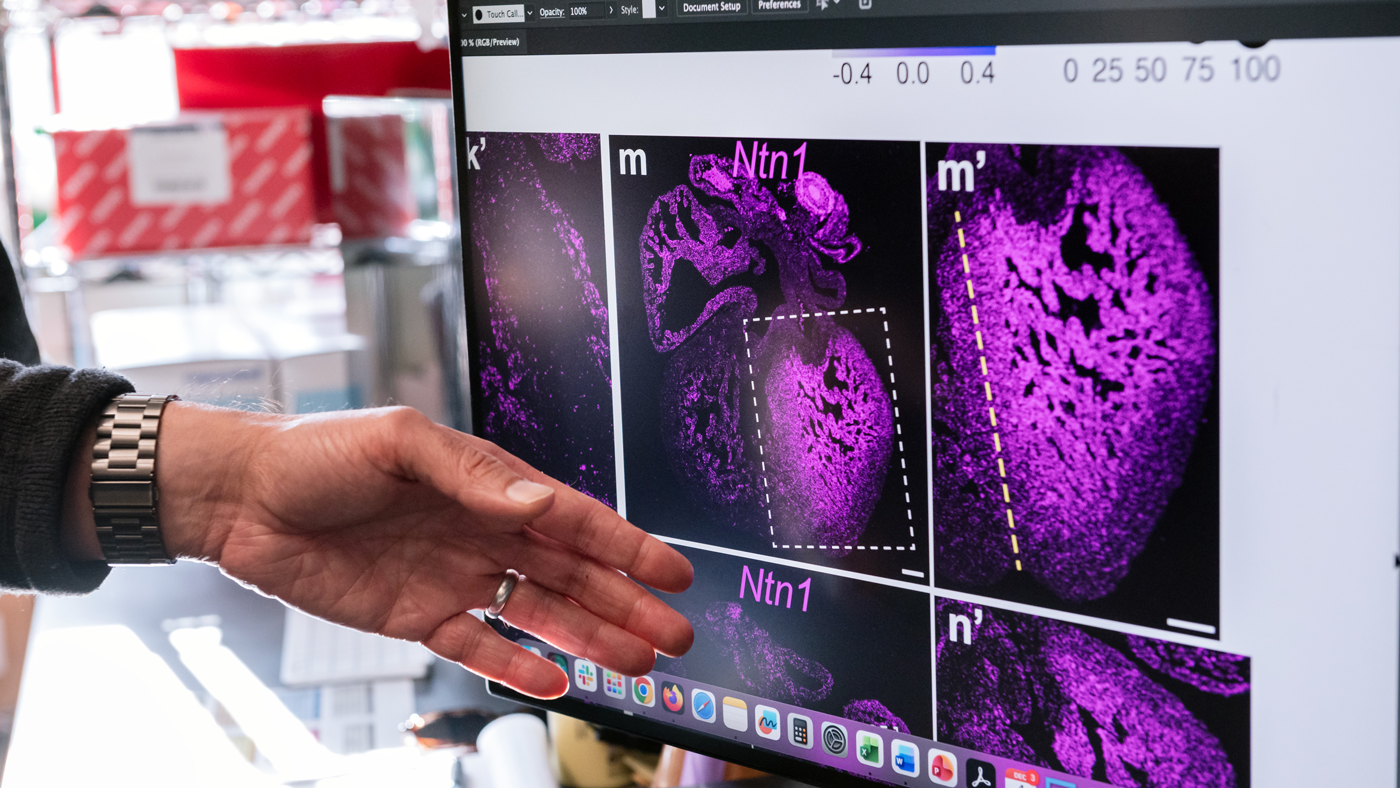

They discovered that TBX5 controls the levels of two other molecules, SLIT2 and Netrin-1, that were already well known for their roles in brain development, where they help neurons find their correct positions. But neither protein had been implicated in the heart before.

“In the brain, these molecules guide cells to the right place,” Kathiriya says. “We found they’re doing something remarkably similar in the heart.”

The study's findings could point toward new drugs to treat or prevent certain types of heart defects. The image on the monitor shows where Netrin-1 is active in a developing heart.

Mice lacking either of these molecules developed disrupted compartment boundaries and holes in their interventricular septum. Moreover, when the researchers adjusted levels of Netrin-1 in mice with TBX5 mutations, they partially prevented the heart defects. The finding could point toward new drugs for preventing or treating Holt-Oram Syndrome or other heart defects caused by a malformed boundary compartment.

“Unlike transcription factors like TBX5, signaling molecules like SLIT2 and Netrin-1 are targets we can potentially manipulate with drugs,” Kathiriya says. “These pathways are already being targeted in cancer and other diseases.”

The researchers plan to continue studying how these molecules work in the developing heart, hoping to identify additional genetic causes of birth defects and therapeutic targets.

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About the Study

The paper, “A disrupted compartment boundary underlies abnormal cardiac patterning and congenital heart defects,” was featured on the cover of the journal Nature Cardiovascular Research in January 2026.

The authors are Irfan S. Kathiriya, Martin Dominguez, Kavitha Rao, Jonathon M. Muncie-Vasic, W. Patrick Devine, Kevin Hu, Swetansu Hota, Bayardo Garay, Diego Quintero, Piyush Goyal, Reuben Thomas, Tatyana Sukonnik, Dario Miguel-Perez, Sarah Winchester, Emily Brower, and Benoit Bruneau of Gladstone; Megan Matthews of UCSF; and André Forjaz, Pei-Hsun Wu, Denis Wirtz, and Ashley Kiemen of Johns Hopkins University.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, The Children’s Heart Foundation, Additional Ventures Innovation Fund, Society for Pediatric Anesthesia, Hellman Family Fund, a UCSF REAC Grant, a UCSF Pediatric Heart Center Catalyst Award, UCSF Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care Research Support, and the Younger Family Fund.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Gladstone NOW: The Campaign

Join Us On The Journey

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

Developed by Gladstone scientists, HIV-seq could uncover new opportunities for treating HIV.

News Release Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabGladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab