Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Rudolf Jaenisch, winner of the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, was the first to demonstrate the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells to treat disease. That's only one of his impressive scientific achievements. Photo: Michael Short/Gladstone Institutes.

Growing up in Germany, Rudolf Jaenisch, MD, seemed destined to become a physician. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all practiced medicine, and biology interested him, so he followed in their footsteps and went to medical school. But his heart wasn’t in it; he was far more intrigued by the lab than the clinic.

“I liked science, I liked asking questions and learning how I could use different tools to find the answers,” Jaenisch says. He decided to forgo a career in medicine and, instead, see where his curiosity might take him.

It took him—and his field—very far.

Over the next several decades, he would pioneer major advancements in epigenetics and stem cell biology, revealing pivotal insights into gene regulation, cellular reprogramming, and the potential of regenerative medicine. And now, these impressive scientific achievements have earned him the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, awarded by Gladstone Institutes and Cell Press.

Established in 2015 by the late Hiro and Betty Ogawa, and now supported by their sons, Marcus and Andrew Ogawa, the prize honors researchers who lead trailblazing work in regenerative medicine using reprogrammed cells.

Jaenisch (center) was presented with the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize by Deepak Srivastava (left) and Shinya Yamanaka (right). He was selected for this prize for pioneering major advancements in epigenetics and stem cell biology. Photo: Michael Short/Gladstone Institutes.

The award also recognizes Gladstone Senior Investigator and Nobel Prize winner Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, and his groundbreaking discovery of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells—adult cells that have been reprogrammed to a “blank slate,” enabling scientists to coax them into becoming any type of cell in the body.

Jaenisch was one of the first scientists to harness the exciting promise of Yamanaka’s discovery, demonstrating the possibility of using iPS cells to treat disease and advancing the methods by which iPS cells can be created and applied.

Today, Jaenisch is a founding member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Rudolf’s natural curiosity and willingness to take creative risks with new methods fundamentally helped shape the field we now call regenerative medicine,” says Deepak Srivastava, MD, president of Gladstone and chair of the prize’s selection committee. “To this day, his contributions underpin countless discoveries that continue to move the field forward.”

Jaenisch received the award, along with an unrestricted prize of $150,000 USD, during a ceremony held at Gladstone in San Francisco on Dec. 1.

Compelled by Curiosity

Jaenisch enjoyed the first part of his medical training at the University of Munich in Germany.

“In the beginning, it was very interesting to learn about physiology, chemistry, biochemistry,” Jaenisch says. “But then came the clinical semesters, which meant competing for space in very crowded rooms. I got quite frustrated, and that helped me realize I did not want to be a physician.”

Instead, after completing his medical degree in 1967, he took a postdoctoral position at the Max Planck Institute in Munich. There, in the lab of virologist P. H. Hofschneider, PhD, he studied bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria. That experience solidified his decision to stick with science instead of clinical work.

“Everyone I knew who did science went to America,” Jaenisch says. So, he wrote an inquiry letter to the virologist Arnold Levine, PhD, at Princeton University in New Jersey. To his surprise, Levine promptly sent back an acceptance letter for a postdoctoral position in his own lab, as well as an application for Jaenisch to apply for a National Institutes of Health fellowship.

Over the course of his career, Jaenisch has had a profound impact on the field of regenerative medicine, having influenced multiple foundational concepts and tools. Photo: Michael Short/Gladstone Institutes.

Jaenisch was selected for the fellowship and started at Princeton in 1970, where he dove into research on SV40, a virus that causes tumors. He became fascinated by the question of why SV40 caused skin tumors in mice, but not brain, liver, or kidney tumors. Did it only infect skin cells, or could it also infect other cells but not transform them into cancer?

“Then I read probably the most important paper of my entire career,” Jaenisch says.

It was a manuscript by renowned embryologist Beatrice Mintz, PhD, that reported new findings about the genetics of mouse pigmentation, using a novel method for combining mouse embryos from parent mice with known traits to create what are known as composite embryos.

“I thought her method for making mouse embryos was the greatest thing ever, and that a similar approach could help answer my question,” Jaenisch says. “I thought if I could put SV40 DNA into an early mouse embryo, I could ensure that every cell would be infected and finally understand how SV40 operates.”

He reached out to Mintz, who was initially skeptical but then invited him to conduct the experiment in her lab at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. There, he received intensive training from Mintz on working with mouse embryos.

Jaenisch successfully used Mintz’s methods to create mice that should carry SV40 in every cell. But no standard tools yet existed to confirm if they did. All he knew was that the mice did not develop any tumors.

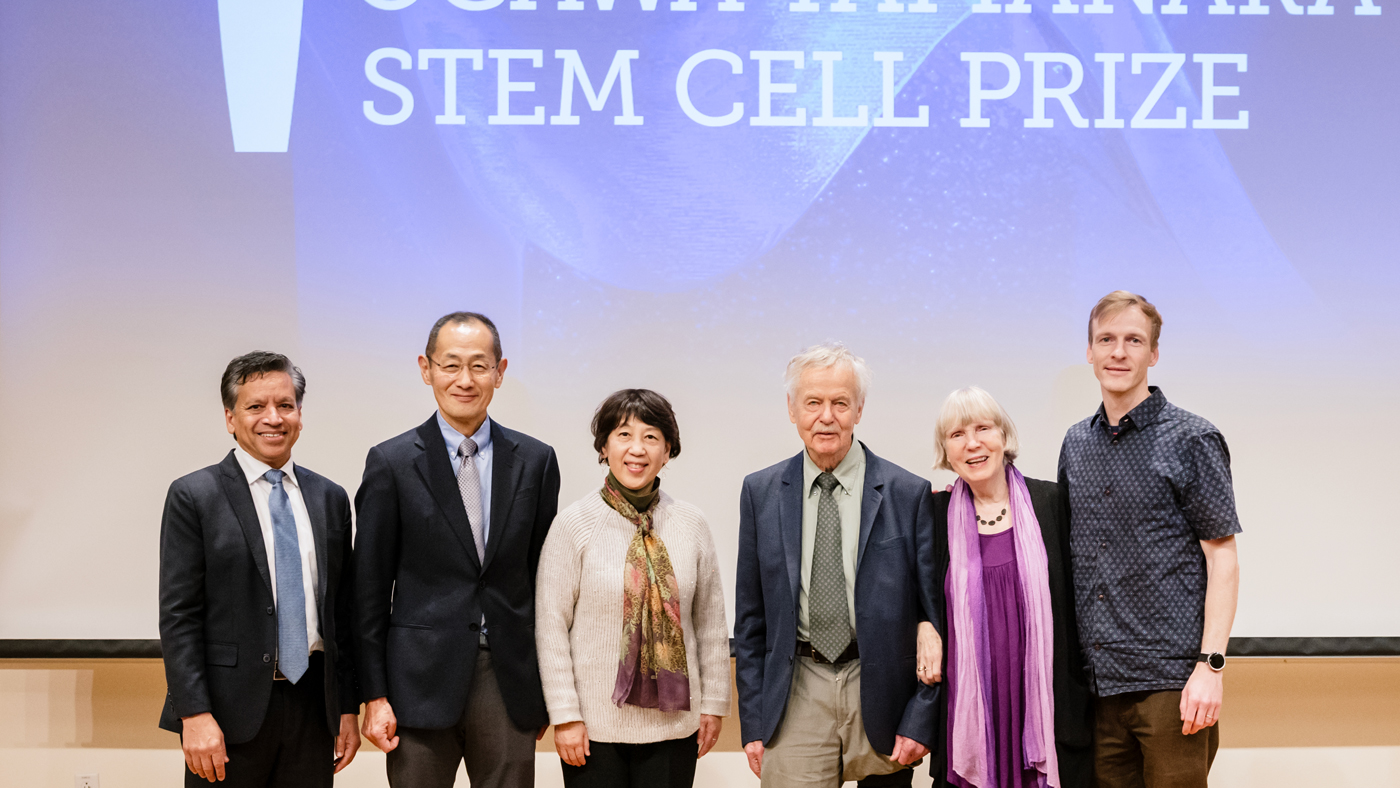

Jaenisch posing on stage at the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize ceremony held at Gladstone on December 1, 2025. Left to right: Deepak Srivastava, Shinya Yamanaka and his wife Chika Yamanaka, Rudolf Jaenisch and his wife, Alexa Fleckenstein, with their son, Johan Jaenisch. Photo: Michael Short/Gladstone Institutes.

Then, he accepted an offer to start his own lab at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Soon after, Stanford University geneticist Paul Berg, PhD, suggested to Jaenisch that he use a heat-based technique called “nick translation” to examine the DNA of the tumor-free mice. To his surprise, the mice did indeed carry SV40 DNA throughout their bodies; in their brains, kidneys, and livers.

The term did not yet exist, but these mice were the first-ever “transgenic” animals—organisms with DNA from another species that has been artificially, and deliberately, incorporated into their genome. Less than one year later, working closely with colleagues at the Salk Institute, Jaenisch confirmed that mice with the SV40 DNA incorporated as embryos could pass it along to their future offspring.

“I cannot overstate the significance of this work,” Srivastava says. “It set the stage for the creation of genetically engineered animal models of human disease, which are used by scientists around the world and continue to drive biomedical discovery today.”

Embryos and Epigenetics

In 1977, Jaenisch returned to Germany to start a new position at the Heinrich Pette Institute in Hamburg. There, he would lead key advancements in the understanding of embryonic development and epigenetics—how genes are controlled without changing the DNA sequence.

At his new lab, he and his colleagues developed a keen interest in creating transgenic mice using different viruses. In some cases, the viral DNA would integrate into the mouse genome in the middle of a gene, mutating it and disrupting its expression. This method, dubbed “insertional mutagenesis,” enabled them to identify certain mouse genes, such as the gene encoding the protein collagen, that are important for healthy embryonic development.

In an ambitious series of related experiments, the team made the major discovery that, in mouse embryos, gene expression is controlled by adding small molecular components known as methyl groups to DNA, without changing the DNA sequence itself—a process called DNA methylation.

In fact, DNA methylation turned out to explain the earlier mystery of why tumors appeared in adult mice newly infected with SV40, but not in transgenic mice with SV40 DNA inserted into their genome as embryos. In embryos, SV40 DNA immediately gets silenced through methylation, preventing tumors, but the same process does not occur in adult mice.

“It is really a wonderful surprise to be recognized in this way so late in my career. Being selected by my colleagues who are at the top of the field themselves is a huge honor and very important to me.”

After seven years in Hamburg, Jaenisch received an invitation from Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore, PhD, to be a founding scientist at Whitehead Institute. So, in 1984, he returned to the U.S. Around that same time, a tool known as homologous recombination had been invented, enabling scientists to target and inactivate specific genes in mouse embryos in order to study their function.

“As soon as I learned about it, I wanted to use this tool at Whitehead,” Jaenisch says. “We used homologous recombination to answer questions about many, many mouse genes, but certainly one of the most interesting ones was DNA methyltransferase.”

When Jaenisch’s team inactivated DNA methyltransferase—which is required for DNA methylation—the mutant mouse embryos all died very early, showing for the first time that DNA methylation is necessary for survival. They also discovered that DNA methylation can play a major role in cancer, further underscoring the importance of epigenetics in biomedical research.

At the Forefront of Discovery

Jaenisch continued to embrace new technologies that he believed could help answer his questions.

“In the late 90s, two really exciting things happened: Dolly, the famous cloned sheep, was announced, and a year later, the first cloned mouse,” Jaenisch says. “I immediately thought that cloned mice could be very valuable for studying development and disease.”

Over the next few years, Jaenisch and his team successfully cloned their own mice and published innovative experiments demonstrating that cloning could be used therapeutically in mice to correct genetic defects.

Then, in 2006, Yamanaka announced his discovery of a way to reprogram adult cells to create iPS cells. At first, many people dismissed the method, feeling it was too simple to work. But Jaenisch had faith in Yamanaka.

“I already knew and respected him, and I could tell he had conducted this very courageous experiment very carefully,” Jaenisch says.

The following year, Jaenisch’s lab was one of three groups to independently demonstrate that Yamanaka’s iPS cells were identical to embryonic stem cells, confirming his success.

“Nobody could doubt the method anymore, and it led to an explosion of research,” Jaenisch says.

Jaenisch shared remarks at the ceremony for the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, which he received for revealing pivotal insights into gene regulation, cellular reprogramming, and the potential of regenerative medicine. Photo: Brittany Hosea-Small/Gladstone Institutes.

For the next decade, Jaenisch played a pioneering role in refining and advancing the methods used by scientists around the world to create and study iPS cells. He was also the first to demonstrate the potential of iPS cells to treat disease.

In a groundbreaking experiment, he corrected the gene that causes sickle cell anemia in iPS cells derived from the skin of mice with the disease. After coaxing the corrected cells into becoming blood cells, he transplanted the cells into the mice, effectively curing them. He achieved similar success in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease.

The next pivotal moment for Jaenisch’s research came in 2012, with the introduction of the gene-editing tool CRISPR, which was co-discovered by Gladstone Senior Investigator Jennifer Doudna, PhD. Jaenisch and his team quickly figured out how to harness CRISPR to conduct experiments in mouse embryos far more efficiently, reducing some experimental timelines from a few years to a few weeks.

Since then, they have used CRISPR to gain new insights into the mechanisms underlying such conditions as Rett syndrome and fragile X syndrome—genetic disorders that cause a variety of developmental problems.

“The invention of CRISPR was another incredible watershed moment,” Jaenisch says. “We hope our work with CRISPR could lead to better treatments for human disease.”

A Foundational Legacy

Jaenisch’s impact on regenerative medicine has been profound and wide-ranging, with multiple foundational concepts and tools in the field bearing his influence. He is a co-author on more than 500 research papers, was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2003, and was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Barack Obama in 2010. He has also mentored many generations of scientists who further advanced the field.

Now, Jaenisch’s curiosity has led him back to where his research began: viruses.

“After the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020, I became really interested in why infected people often continue to test positive for viral RNA for many months, long after the virus is no longer detectable,” Jaenisch says.

His team has now found evidence that small portions of the viral genome may get integrated into the genome of infected cells. They have also developed an assay to detect such integration.

“I would like to finish out my career by solving this problem,” Jaenisch says.

The Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize was originally established by the late Hiro and Betty Ogawa, and is now supported by their sons, Andrew and Marcus Ogawa. It also recognizes Shinya Yamanaka's Nobel-Prize winning discovery of iPS cells. Left to right: Andrew Ogawa, Valentina Ogawa, Mako Ogawa, Chika Yamanaka, Shinya Yamanaka, Athena Ogawa, Lisa Ogawa, Leonidas Ogawa, and Marcus Ogawa standing for a photo at the ceremony for the 2025 award. Photo: Brittany Hosea-Small/Gladstone Institutes.

Reflecting on being named the 2025 recipient of the Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, he says he is deeply honored.

“It is really a wonderful surprise to be recognized in this way so late in my career,” Jaenisch says. “Being selected by my colleagues who are at the top of the field themselves is a huge honor and very important to me.”

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabSix Gladstone Scientists Named Among World’s Most Highly Cited Researchers

Six Gladstone Scientists Named Among World’s Most Highly Cited Researchers

The featured scientists include global leaders in gene editing, data science, and immunology.

Awards News Release Corces Lab Doudna Lab Marson Lab Pollard Lab Ye LabBringing Modern Science to Vitamin Biology: Isha Jain Wins NIH Transformative Research Award

Bringing Modern Science to Vitamin Biology: Isha Jain Wins NIH Transformative Research Award

Leveraging modern scientific tools and techniques, Jain intends to transform our understanding of the critical roles that vitamins play in health and disease.

Awards News Release Cardiovascular Disease Jain Lab Metabolism