Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

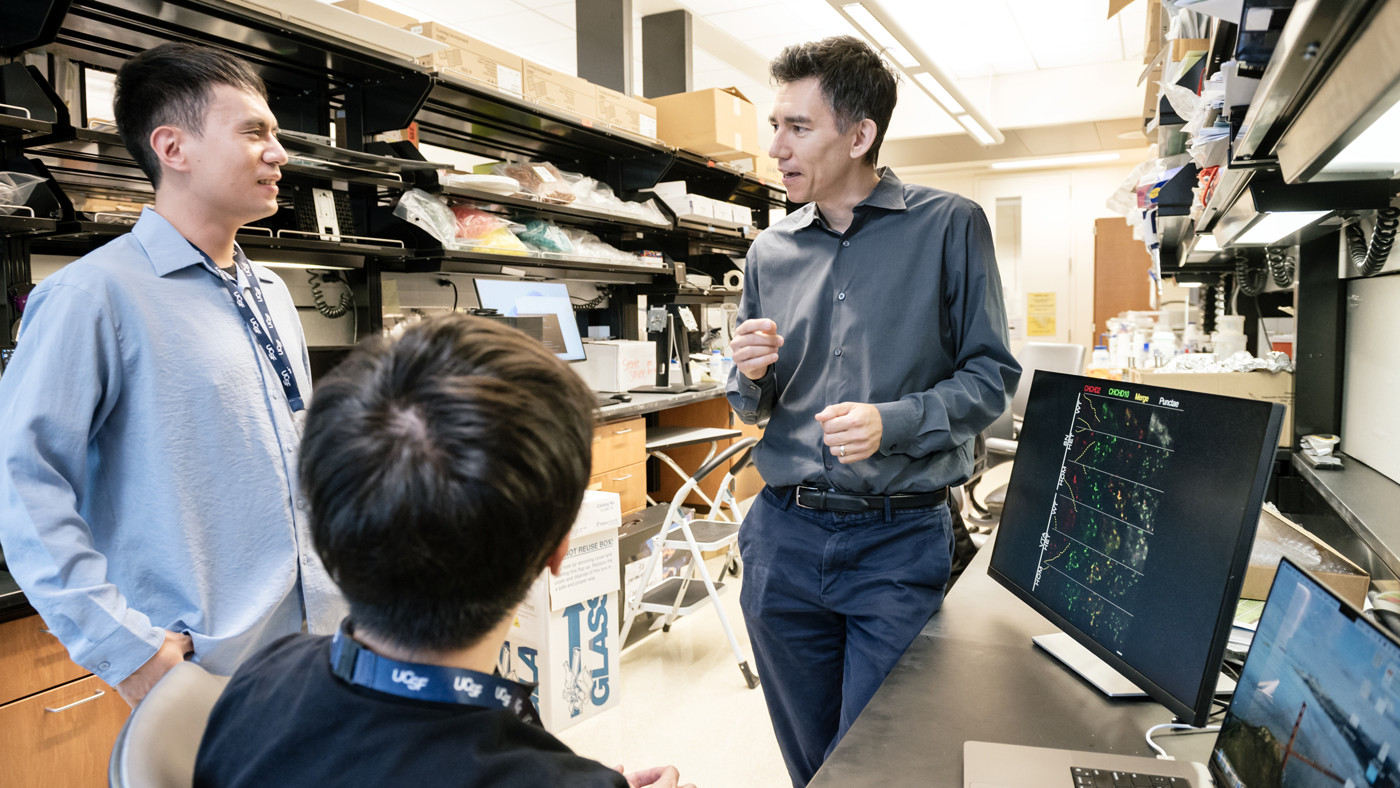

Gladstone Investigator Ken Nakamura (right) led a study that strengthens the links between energy breakdown in cells and the onset of Parkinson’s, potentially illuminating new paths for treatment. Here, Nakamura discusses the findings with Szu-Chi Liao (left) and Kohei Kano (middle), who are co-first authors of the study.

For decades, scientists have known that mitochondria, which produce energy inside our cells, malfunction in Parkinson’s disease. But a critical question remained: do the failing mitochondria cause Parkinson’s, or do they become damaged when brain cells die during the course of disease?

Many studies have sought to answer this question over the years. Yet, progress has been slow—in large part due to the limitations of animal models used to research this highly complex disease.

Now, a team of scientists from Gladstone Institutes has achieved a new level of clarity through discoveries demonstrating that dysfunctional mitochondria can initiate the onset of Parkinson’s.

The study, which appears in Science Advances, centers on a unique mouse model that exhibits symptoms of a rare, inherited form of Parkinson’s that is otherwise indistinguishable from the most common form, which develops later in life and accounts for about 90 percent of cases.

“This mouse model provides some of the most compelling evidence to date for how mitochondrial dysfunction can cause typical late-onset Parkinson’s disease,” says Gladstone Investigator Ken Nakamura, MD, PhD, who led the study. “I hope that ultimately, understanding this link will point to new drug targets to prevent or treat all forms of the disease.”

The mouse model used in the study carries a mutation in a mitochondrial protein known as CHCHD2, which causes a rare, inherited form of Parkinson’s. Because that variant of the disease mirrors the more common form—which is known as “sporadic” Parkinson’s—the researchers hypothesize their insights carry over to a large proportion of those cases.

Szu-Chi Liao (left) and Kohei Kano were part of a team that demonstrated how dysfunctional mitochondria can initiate the onset of Parkinson’s. The study appears in Science Advances.

Mimicking Human Disease

Parkinson’s, the second-most-common neurodegenerative disorder, affects more than 1 million people in the U.S., with most cases diagnosed after the age of 60. Over time, the brain loses its ability to produce the neurotransmitter dopamine, which helps coordinate movement. This process leads to the movement-related symptoms such as tremor, stiffness and gait problems.

However, many forms of Parkinson’s exist—and the most common sporadic form has many subtypes and underlying mechanisms driven by an array of different genetic and environmental factors.

The heterogeneity of the disease has presented challenges for researchers, and mice carrying some mitochondrial mutations that are linked to Parkinson’s disease in humans fail to develop the key features of the sporadic disease, says Nakamura, who conducts his research at the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease.

Using their new mouse model, the scientists were able to delineate a cascade of steps by which mitochondrial dysfunction may trigger the core cellular changes seen in people with rare or more common forms of Parkinson’s.

“We were able to watch, step by step, how mitochondria start to fail and how this process eventually leads to the accumulation of alpha-synuclein—the protein that builds up in pathological alterations in the brain called Lewy bodies in nearly all Parkinson’s patients,” says Kohei Kano, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Nakamura’s lab and a co-first author of the study.

A Perfect Storm

The researchers showed that the mutated CHCHD2 protein accumulates in mitochondria, causing them to become swollen and distorted. Over time, cells with these dysfunctional mitochondria stop using their normal energy-production pathways, shifting to less-efficient means of burning sugar.

As the mitochondrial metabolism shifts, oxidative stress increases within cells due to a buildup of unstable molecules known as reactive oxygen species. The reason for this appears to be that the CHCHD2 mutation interferes with proteins that normally clean up the destructive molecules.

“A notable finding was that alpha-synuclein doesn’t accumulate until after levels of reactive oxygen species rise,” says co-first author Szu-Chi Liao, PhD, a former member of the Nakamura lab who is now at UC San Francisco. “This order of events is consistent with our hypothesis that oxidative stress is causing the alpha-synuclein to aggregate.”

Ken Nakamura (right) and his team hope their findings will point to new drug targets to prevent or treat all forms of the disease.

Broader Lessons for Parkinson’s

To confirm their findings in humans, Nakamura collaborated with scientists at the University of Sydney in Australia to examine post-mortem brain tissue from people with sporadic Parkinson’s. The Sydney team, led by Glenda Halliday, PhD, found that the CHCHD2 mitochondrial protein accumulated in early-stage aggregates of alpha-synuclein within vulnerable dopamine-producing neurons in the human patients.

“This work is a blueprint for how a mitochondrial protein can be disrupted and actually cause Parkinson’s disease,” Nakamura says. “But there could be other triggers that set off this same sequence of events involving mitochondrial damage, energy problems, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and finally, abnormal accumulation of additional proteins.”

The scientists are now planning additional studies to understand how CHCHD2 influences oxidative stress and whether it may contribute to the development of sporadic Parkinson’s. They also aim to investigate if drugs that block reactive oxygen species and boost cellular energy could stop the chain of events that lead to disease.

For Media

Kelly Quigley

Director, Science Communications and Media Relations

415.734.2690

Email

About the Study

The paper “CHCHD2 Mutant Mice Link Mitochondrial Deficits to PD Pathophysiology” was published in the journal Science Advances on November 14, 2025. In addition to Ken Nakamura, Kohei Kano, and Szu-Chi Liao, authors are: Mai Nguyen, Jonathan Meng, Jeffrey Simms, and Yoshitaka Sei of Gladstone; Sadhna Phanse, Mohamed Taha Moutaoufik, Kirsten Broderick, Tatiana Saccon, Hiroyuki Aoki, and Mohan Babu of University of Regina, a co-corresponding author of the paper; Elyssa Margolis and Eric Huang of UC San Francisco; YuHong Fu, Zac Chatterton, Felicia Xaveria Suteja, and Glenda Halliday of University of Sydney; and Kevin McAvoy and Giovanni Manfredi of Weill Cornell Medicine. (Moutaoufik is now at Mohammed VI Polytechnic University and Huang is now at Washington University.)

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG065428, RF1 AG064170, RR18928), Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP1481 020529) through the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the UCSF Bakar Aging Research Institute, the UCSF Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-154318, PJT-186258), the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Barry & Marie Lipman Parkinson’s Disease Breakthrough Initiative, the Joan and David Traitel Family Trust, Betty Brown’s Family, the Dr. and Mrs. C.Y. Soong Fellowship, the Government Scholarship to Study Abroad by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan, a Berkelhammer Award for Excellence in Neuroscience, Parkinson Canada, and an Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award at UCSF (K12GM081266).

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Featured Experts

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

Developed by Gladstone scientists, HIV-seq could uncover new opportunities for treating HIV.

News Release Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabGladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab