Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Gladstone's Alex Marson, along with collaborators at Arc Institute and UC San Francisco, developed a way to create more effective T cell therapies that can potentially treat cancer, autoimmune diseases, and other conditions.

A growing number of cancer treatments known as CAR-T cell therapies genetically modify a patient’s own immune cells to target and destroy cancer throughout their body.

These therapies have shown great success against certain blood cancers such as leukemias and lymphomas, but tend to fail when applied to solid tumors that comprise the vast majority of cancer cases.

That’s because T cells—the immune cells at the core of CAR-T therapies—can become suppressed or exhausted when faced with solid tumors. Over the years, scientists have attempted to give those cells stronger cancer-fighting power by altering many of their genes, but doing so has potential to damage the cells’ DNA or even destroy the cells.

Now, a breakthrough from researchers at Arc Institute, Gladstone Institutes, and UC San Francisco (UCSF) may overcome these and other limitations of today’s CAR-T cell therapies.

Rather than adding more genetic modifications to the therapeutic T cells, the scientists found a way to make "epigenetic" changes, which modify the cells’ behavior without altering their underlying DNA sequence. Detailed in Nature Biotechnology, the epigenetic editing method created enhanced CAR-T therapies, while also overcoming key manufacturing and scalability issues.

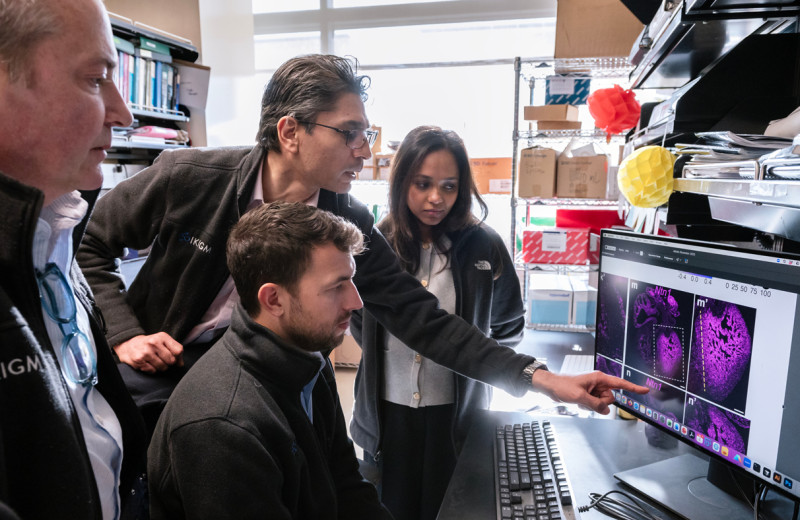

Marson and his collaborators developed a new platform to reprogram CAR-T cells so they can better destroy cancer cells.

“Our new platform offers broad hopes for developing distinct programs to treat not only cancer, but a wide range of different diseases,” says Alex Marson, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone-UCSF Institute of Genomic Immunology and co-senior author of the study.

On and Off Switches

While genetic changes permanently alter the DNA code, epigenetic changes leave those sequences intact; what’s changed are instructions about which parts of the code are active or inactive. As part of the new platform, the team used technologies called “CRISPRoff” and “CRISPRon” to instruct cells to turn off certain genes or re-activate genes that would otherwise be silenced. And unlike traditional CRISPR approaches that require cutting the DNA helix, which can harm or kill T cells, these epigenetic editors can modify up to five genes simultaneously while maintaining high cell survival rates.

Scientists used genetic engineering to program T cells to search for cancer cells, then combined it with so-called “epigenetic engineering” to program the strength of their anti-cancer functions.

“The T cells essentially memorize our programming instructions,” says co-senior author Luke Gilbert, PhD, an Arc Institute core investigator and an associate professor at UC San Francisco (UCSF). “We deliver the epigenetic editors for just a couple of days, but the gene silencing effects remain stable through dozens of cell divisions and multiple rounds of immune activation.”

Innovation in Action

To demonstrate the platform’s potential, the researchers created enhanced CAR-T cells by first inserting cancer-targeting receptors, and then simultaneously using CRISPRoff to silence the gene RASA2, which normally acts as a brake on T cells’ ability to destroy cancer cells.

The dual-engineered cells maintained their cancer-killing ability through repeated challenges in laboratory tests, while CAR-T cells where RASA2 was not silenced became exhausted. In mouse models of leukemia, the enhanced CAR-T cells provided significantly better tumor control and improved survival compared to standard CAR-T approaches.

“Instead of just adding targeting capabilities, we can systematically reprogram how these cells function in a scalable manner to create more effective therapeutic products,” says first author Laine Goudy, a PhD student in the Marson and Gilbert labs. “The data in this paper could support moving directly into clinical trials for certain applications.”

“Our new platform offers broad hopes for developing distinct programs to treat not only cancer, but a wide range of different diseases.”

Notably, CRISPRoff works with cell manufacturing protocols already used to produce FDA-approved CAR-T treatments, requiring only the conversion of research-grade reagents to clinical-grade versions. The research team is considering next steps for testing the technology in humans.

Beyond cancer, the approach opens new possibilities for treating autoimmune diseases, creating new transplant medicines, and addressing other areas of medicine in which reprogrammed T cells could provide benefit to patients.

“When we started, we weren’t sure this would be successful in T cells, and it took years of methodical optimization to overcome some fundamental challenges, but it’s been so gratifying to see that the core technology is extremely robust,” Gilbert says. “CAR-T therapies are an incredible success story, but in the context of solid tumors we believe our approach could boost the next generation of CAR-T approaches to benefit patients.”

In addition to Marson and Gilbert, co-senior authors of the paper are Brian Shy, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the UCSF Department of Laboratory Medicine and director of the UCSF Investigational Cell Therapy Program, and Justin Eyquem, PhD, an affiliate of the Gladstone-UCSF Institute for Genomic Immunology and associate professor in the UCSF Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

For Media

Kelly Quigley

Director, Science Communications and Media Relations

415.734.2690

Email

About the Study

The study, "Integrated Epigenetic and Genetic Programming of Primary Human T Cells,” was published in Nature Biotechnology on October 21, 2025. Authors are Laine Goudy, Alvin Ha, Ashir A. Borah, Jennifer M. Umhoefer, Lauren Chow, Carinna Tran, Aidan Winters, Alexis Talbot, Rosmely Hernandez, Zhongmei Li, Sanjana Subramanya, Abolfazl Arab, Nupura Kale, Jae Hyun J. Lee, Joseph J. Muldoon, Chang Liu, Ralf Schmidt, Philip Santangelo, Julia Carnevale, Justin Eyquem, Brian R. Shy, Alex Marson, and Luke A. Gilbert.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, the Lloyd J. Old STAR award from the Cancer Research Institute, the Simons Foundation, the CRISPR Cures for Cancer Initiative, the UCSF CRISPR Cures for Cancer Initiative, the UCSF Living Therapeutics Initiative, the Cancer Research Institute Irvington postdoctoral fellowship, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists, the Lydia Preisler Shorenstein Donor Advised Fund, the Grand Multiple Myeloma Translational Initiative, the Baszucki research funding for lymphoma, and Arc Institute. The researchers have filed patent applications related to CRISPRoff technology.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau LabGene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Gene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Scientists at Gladstone show the new method could treat the majority of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Conklin Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingGenomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Genomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Findings of the new study in Nature could streamline scientific discovery and accelerate drug development.

News Release Research (Publication) Marson Lab Genomics Genomic Immunology