Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Karin Pelka starts a new lab at Gladstone to study the innate immune system and find new ways to fight cancer and other diseases.

For the immune system, which protects us from bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens, communication is of utmost importance. The components of the system—antibodies, T cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and many others—use a complex communication structure to recognize threats and coordinate the responses that protect us.

Karin Pelka (she/her), PhD, is studying the complex communication networks used by the immune system, working toward better utilizing its innate branch to fight cancer and other diseases. She now joins Gladstone Institutes as an assistant investigator, with a long-term goal of understanding how innate immune mechanisms shape anti-tumor immunity.

“Our immune system is really powerful because it’s very adaptable; it can learn from and adapt to various situations,” she says. “We want to find new ways of using different weapons of the immune system to tackle disease. For now, I’m focused on cancer, but this is really a concept that broadly applies to other diseases.”

A graduate of the University of Bonn with a PhD in innate immunity, Pelka joins the Gladstone-UCSF Institute of Genomic Immunology after 5 years as a postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. She is now also an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at UC San Francisco.

“We need a deeper understanding of how the cells in the human immune system communicate and work together to develop powerful new treatments for a range of diseases,” says Alex Marson, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone-UCSF Institute of Genomic Immunology. “Karin’s expertise in harnessing the power of the innate immune system, her ability to leverage the latest genomic and gene-editing technologies, and her interest in working as part of an interdisciplinary team will help us make dramatic progress on our mission.”

Targeting the Innate Immune System

The human immune system has two major branches: an adaptive system that learns to detect and destroy threats in a highly specific way, by targeting one specific viral protein, for example, and a less specialized, but broader innate system. Until now, researchers have primarily looked to the adaptive system as a means to fight disease, but Pelka believes that should change.

“The innate system is really important, both to put up the first line of defense and to recruit the more specialized adaptive system to a site of infection or injury,” she explains. “So, by targeting the innate immune system and manipulating its communication networks, we could have a greater impact on disease than by focusing on the adaptive system alone. We could also help address situations where patients cannot raise an adaptive immune response, or cannot do so fast enough.”

Pelka’s goal is to better understand how to target the innate immune system. In her work so far, she has developed important insights into how the different genes and communication pathways of immune and non-immune cells work together to generate a powerful response to disease, particularly to cancer.

This research became possible only with the recent development of technologies that allow the study of human tissues, and the individual cells within them, in great detail. Previously, researchers were limited to the information they could tease out of mouse models or cell lines in dishes.

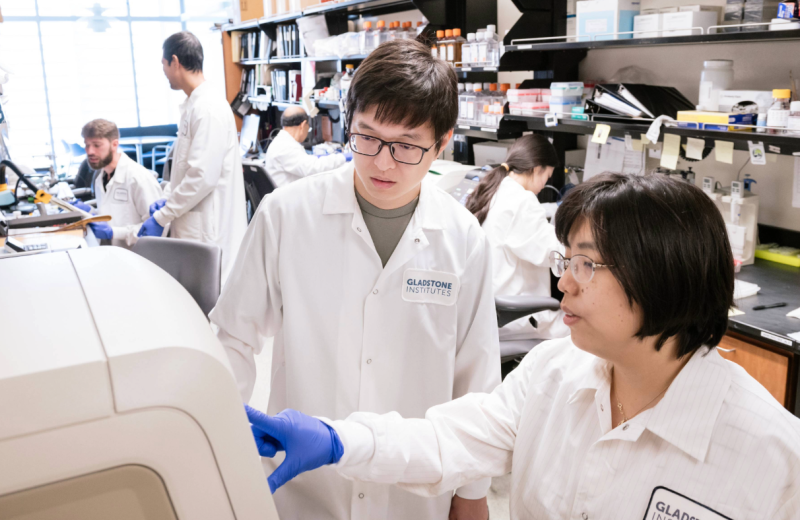

Scientists in Pelka's lab use the latest technologies to better understand the role of the innate immune system in malignant tumors.

“In my previous work, my colleagues and I took tumor tissues from patients, and then used single-cell RNA sequencing to understand all of the individual cell types and gene programs that make up these tumors,” Pelka says. “By analyzing a large cohort of patients, we were able to understand how these different cell types work together as functional modules.”

While new technology-based tools are moving into labs, the number of clinical trials on the impact of different immunotherapy regimens and combination treatments is expanding as well. This provides Pelka with the opportunity to study how therapies might change the interactions between malignant tumor cells and immune cells, and help her identify what the immune system is doing.

“I try to observe and profile what is going on in human tissues, and take those findings back to the laboratory bench,” says Pelka. “There, I can use my experimental background to test my hypotheses in simple model systems in order to understand how we can manipulate the immunological processes.”

For this step, she taps into genome-editing tools that have made it possible to easily manipulate the genes of human cells.

“Using tools like CRISPR to perturb cells in scalable ways has really enabled us to discover novel pathways and mechanisms more quickly to understand what is happening in humans,” she adds.

Inspired by Nature’s Creativity

Pelka’s work also has a personal component.

Her father was diagnosed with cancer when she was 9 years old, and the years since have been a roller coaster. Luckily, medicine and an increasingly better understanding of his underlying immune deficiency disorder have saved his life.

“It’s quite powerful to see the speed at which developments are being made, so being diagnosed with cancer now is not the same as it was when I was a child,” says Pelka. “You know that patients are waiting for these treatments to improve. The importance of making those advances is on my mind a lot.”

Fascinated with nature's creativity, Karin Pelka knew she wanted to work in immunology from a young age.

Curiosity about how nature works led Pelka to her current career path. After high school, she enrolled in a one-year interdisciplinary study program with courses ranging from arts and philosophy to biochemistry and math. When she first read about how neutrophils—immune cells that are the first line of defense when infection strikes—expel their own sticky DNA as a fishing net to capture invading bacteria, her mind was made up.

“I was fascinated by how creative nature is, and the ways that it tries to deal with threats,” she says. “So I decided I really wanted to work in immunology.”

Like the immune system networks she studies, Pelka thrives in interdisciplinary environments where specialists from different backgrounds—from immunology to computational modeling—work together and learn from each other. She is excited about the collaborative environment at Gladstone and looks forward to working with her new colleagues.

“I love the energy at Gladstone and the very collaborative, interdisciplinary spirit,” she says. “It’s a group of extremely talented and motivated people from very different backgrounds, working together in a concentrated space toward a unified mission. That was a big, big draw for me.”

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

About Karin Pelka

Karin Pelka, PhD, is an assistant investigator at Gladstone Institutes. She is also an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at UC San Francisco.

Pelka earned a PhD in innate immunity from the University of Bonn in Germany, where she discovered a key regulatory mechanism that controls the detection of infection- or danger-associated nucleic acids by sensors of the innate immune system. She also contributed to several studies elucidating the role of innate immune sensors in autoimmune diseases such as lupus and in the Western Diet-mediated epigenetic reprogramming of the innate immune system.

As a postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Pelka shifted her interest to cancer immunology and systems biology. She led a cross-disciplinary, multi-institutional, single cell RNA-sequencing and spatial profiling effort on human colorectal cancer. Pelka discovered that these seemingly heterogeneous tumors contained several spatially organized multicellular interaction networks between malignant cells and immune cells.

She is a member of the American Association for Cancer Research, the German Society for Immunology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Immunologie), and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Want to Join the Team?

Our people are our most important asset. We offer a wide array of career opportunities both in our administrative offices and in our labs.

Explore CareersOne Person’s Final Gift to Science Gets Us Closer to an HIV Cure

One Person’s Final Gift to Science Gets Us Closer to an HIV Cure

A new documentary follows Jim Dunn’s end-of-life decision to donate his tissues to HIV research.

Institutional News HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabBeyond Viruses: Expanding the Fight Against Infectious Diseases

Beyond Viruses: Expanding the Fight Against Infectious Diseases

The newly renamed Gladstone Infectious Disease Institute broadens its mission to address global health threats ranging from antibiotic resistance to infections that cause chronic diseases.

Institutional News News Release Cancer COVID-19 Hepatitis C HIV/AIDS Zika Virus Infectious DiseaseFueling Discovery at the Frontiers of Neuroscience: The NOMIS-Gladstone Fellowship Program

Fueling Discovery at the Frontiers of Neuroscience: The NOMIS-Gladstone Fellowship Program

The NOMIS-Gladstone Fellowship Program empowers early-career scientists to push the boundaries of neuroscience and unlock the brain’s deepest mysteries.

Institutional News Neurological Disease Mucke Lab NOMIS