Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

At Gladstone, our scientists aren’t simply using artificial intelligence in their work—they are creating some of the world’s most advanced AI models in biomedical research. Their platforms promise to revolutionize how science is done and lead to new treatments for the most devastating diseases.

Gladstone is launching a series to share the many ways our scientists are using—and developing—AI tools for biomedical research. Each article or video will uncover a fascinating application of this technology and how it’s shaping our health, with this first article giving you a glimpse of the topics to be covered. Sign up for our newsletter to have these stories delivered right to your inbox.

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is all around: it can draft emails, control your home thermostat, generate videos, and even drive cars.

Scientists, too, are building AI models to better understand how human bodies work and what goes wrong in disease. This technology promises to have a monumental impact on health outcomes for patients across the globe. Yet, the use of AI in science doesn’t get as much public attention, and therefore remains a bit of a mystery for the average person.

“AI is a transformative force in biomedical research. It’s empowering scientists, allowing us to go faster and make more insightful discoveries than we ever could through traditional methods.”

—Deepak Srivastava, MD

At Gladstone Institutes, a leader in this fast-moving field, researchers have been developing new AI platforms for decades. These AI tools are paving the way to new treatments and medicines for some of the harshest diseases, from Alzheimer’s to cancer to HIV.

“AI is a transformative force in biomedical research,” says Gladstone President Deepak Srivastava, MD. “It’s empowering scientists, allowing us to go faster and make more insightful discoveries than we ever could through traditional methods. At Gladstone, we’ve been investing in this area for many years, well before the ‘ChatGPT moment’ captured the world.”

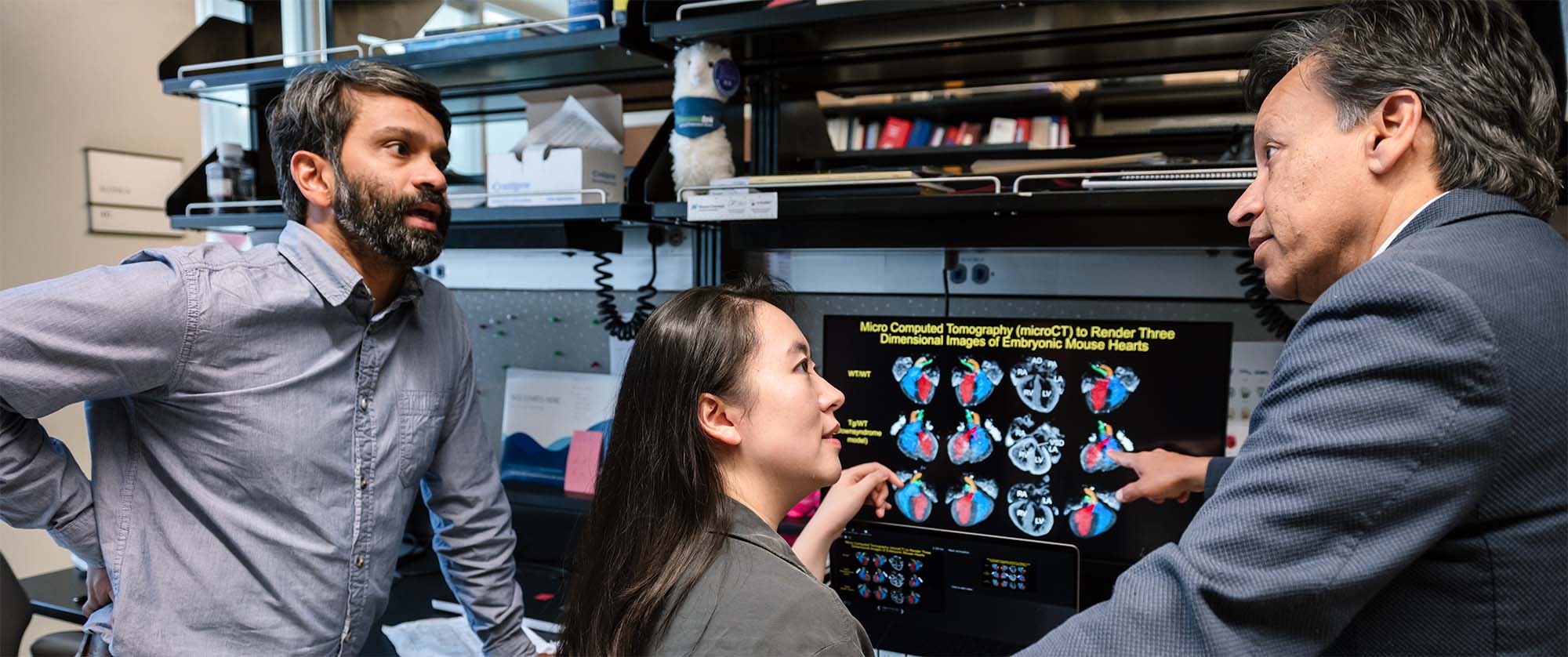

Scientists at Gladstone are using—and more importantly, developing—AI tools in their research, paving the way to new treatments and medicines for some of the harshest diseases, from Alzheimer’s to cancer to HIV. Seen here are Sanjeev Ranade (left), Feiya Li (center), and Deepak Srivastava (right).

At its core, AI is a set of tools that scientists can use to identify complex patterns in data that are too difficult for humans to find, and to predict cause-and-effect relationships.

“AI is necessary in biomedicine because the problems are really hard,” says Katie Pollard, PhD, Director of the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology. “The diseases we tackle are so difficult that we, as humans, can barely fathom their complexity, let alone solve them without computers.”

Deciphering the Complexity of the Human Body

In the early 2000s, it cost approximately $1 billion to decode the first human genome, which consists of all the DNA inside a cell’s nucleus. Today, you can have your genome sequenced for about $300, making it a relatively common occurrence in the clinic.

If you consider that each genome contains 3 billion base pairs—the basic building blocks of DNA—you can quickly get a sense of how much information is generated from a single person, let alone millions of people.

This is where the problem lies.

Only a small number of genetic changes can be enough to explain what causes disease. But how do you interpret data from millions of genomes and pick out the meaningful differences amid a sea of unimportant ones?

And scientists are not only dealing with data from sequenced genomes. Most modern experimental techniques generate massive amounts of complex data that researchers can’t analyze effectively using traditional methods.

“AI is a crucial tool—without it, we would just be awash in all this information and not know what to make of it,” Srivastava says.

At Gladstone, researchers are teaming up to tackle this problem.

Computational scientists are developing unique AI platforms to help identify what change in a gene—or what combination of changes across many genes—can cause a particular disease. They train models that make predictions, which biologists then verify in the lab. This leads to new insights that not only retrain the AI to make it better, but ultimately lead to knowledge that can be turned into potential therapies.

Computational scientists (like Katie Pollard, right, seen here talking to Zhirui Hu, left) are developing unique AI platforms to predict what genetic changes can cause a particular disease, with the ultimate goal of identifying new therapies.

What, Actually, Is AI?

Artificial intelligence, a term that’s been around since the 1950s, is essentially any effort to have a machine mimic human intelligence. Over the past decades, this field has expanded dramatically. Every month, new AI tools and applications emerge, disrupting industries and transforming the way we live our lives.

In biomedical research, the most common form of AI used by scientists falls within a category called machine learning, in which computers learn from data without being programmed with a set of predetermined rules.

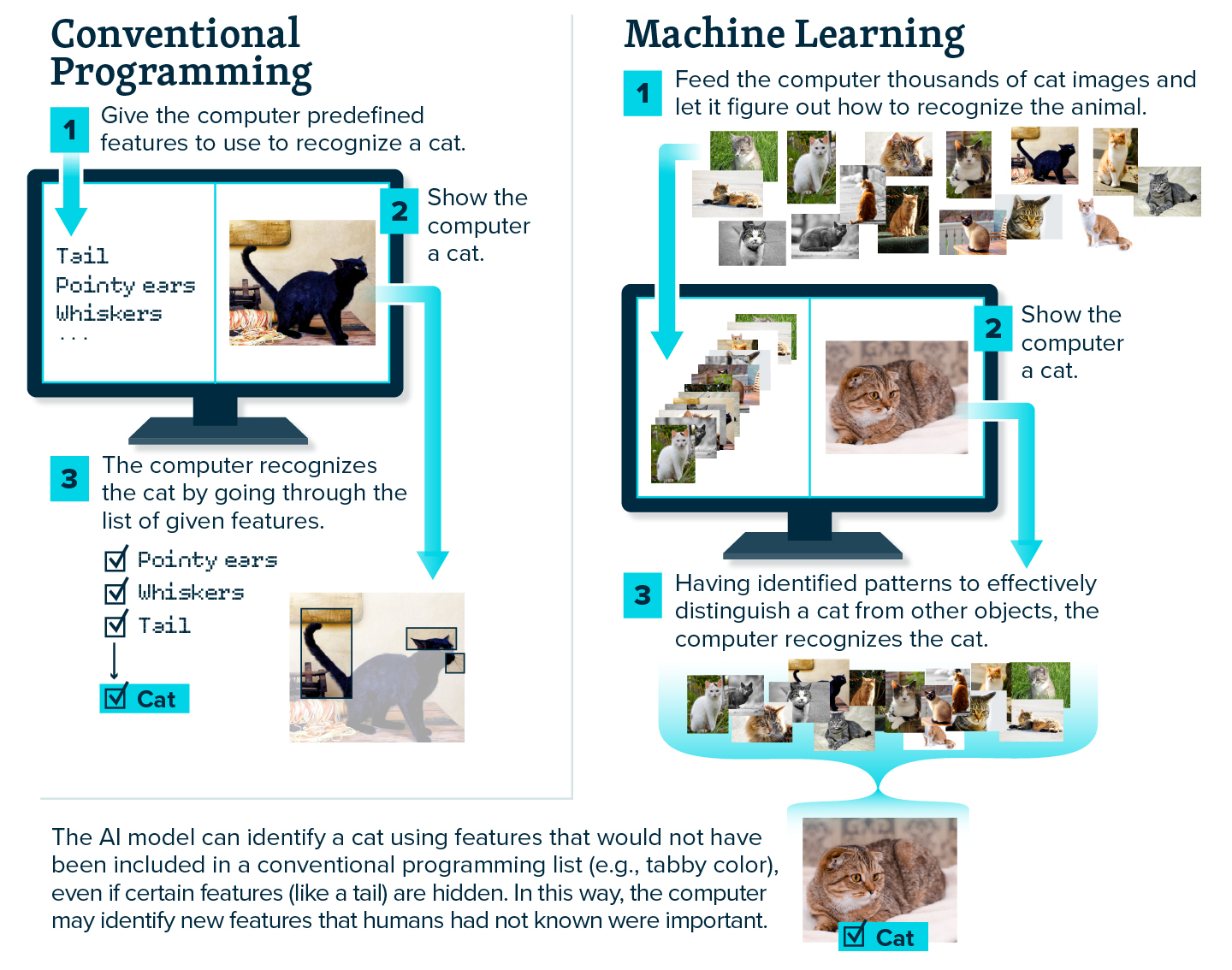

If you think of conventional programming, a person would write a code with specific instructions, like a step-by-step recipe, to teach the computer how to perform a series of operations. In contrast, machine learning would be like giving the computer tons of cakes of varying quality—letting it know which ones are good—and having it figure out the recipe on its own, perhaps even coming up with a better recipe than what was available for it to train on. The AI formulates its own instructions by seeing examples and figuring out patterns, without being told what to do.

So, if you wanted to teach a machine to recognize cats in photos, the conventional approach might involve giving it a detailed list of cat features (pointy ears, whiskers, tail), whereas with machine learning, you would show it thousands of photos of cats. The machine learning model would then learn to recognize the animal on its own from patterns in the examples, by homing in on the minimal number of features required to distinguish a cat from other objects.

A subset of machine learning, called deep learning, has revolutionized the field of AI in the past few years and has become a powerful tool in science.

Deep learning uses artificial neural networks, which consist of nodes—inspired by the interconnected neurons in the human brain—that process information and perform simple mathematical operations. The networks are considered “deep” when they use multiple layers of nodes that can send information back and forth, between and across the layers. The deeper the network, the more complex the operations it can execute. Most foundation models, like Chat GPT, are based on deep learning.

New Predictions, New Hypotheses

One of AI’s unique strengths is its ability to recognize patterns across large datasets, and then use what it learns to anticipate future outcomes. Even in highly complex systems that are not fully understood—like the human body—AI can uncover subtle relationships and make informed predictions.

In biology, that means AI can help researchers understand what happens when cells are sick, find possible new therapeutics targets, and predict how cells will respond to treatments.

“AI is a set of tools to find patterns in data—really, that’s it. Once you have those patterns, though, you can do a million things. You can visualize the data, you can come up with hypotheses, or you can predict what’s going to happen next.”

—Barbara Engelhardt, PhD

“AI is a set of tools to find patterns in data—really, that’s it,” says Gladstone Investigator Barbara Engelhardt, PhD. “Once you have those patterns, though, you can do a million things. You can visualize the data, you can come up with hypotheses, or you can predict what’s going to happen next.”

In fact, Srivastava and Pollard recently leveraged a machine learning model to uncover a key gene that leads to heart defects in babies born with Down Syndrome. The Pollard Lab’s algorithm sifted through the vast amount of data generated by the experiments in Srivastava’s lab, and predicted the gene that was the culprit.

“Even though the data we collected in the lab was not easy to interpret, the AI helped us get the most information out of the experiments as possible,” says Pollard. “And it turns out the causal gene we identified was not on anyone’s radar.”

Their findings could become the basis for novel treatments that prevent heart malformations in people with Down syndrome and related heart defects.

Barbara Engelhardt (pointing at the screen) is one of many computational scientists at Gladstone using AI to find patterns in data, and leveraging this information to generate new hypotheses or predict what’s happening in the human body. (Also seen in the photo is graduate student Ally Nicolella, right.)

Prioritizing the Most Promising Research Avenues

Pollard and Srivastava’s work is one of many examples of how AI can generate new, non-obvious hypotheses for scientists to investigate. Another example is Geneformer, the first foundation model in the world to look at—and predict—gene activity within individual cells.

Created by a Gladstone scientist, Geneformer is what is known as a “transformer,” similar to ChatGPT but for predicting on the computer the impact of changes made to activity of genes. This AI model can be applied to identify what change in a gene is likely causing disease, and what can make the cell healthy again.

Without AI, finding one gene that causes disease—from among the 20,000 genes in the human genome—is as daunting as looking for a needle in a haystack. But AI doesn’t just find the needle; it prioritizes which needles are most likely to become successful therapies, saving millions of dollars in failed lab experiments and years of research during which patients would otherwise suffer.

“AI allows us to prioritize the astronomical number of options and focus on the most promising ones for us to test in the lab.”

—Christina Theodoris, MD, PhD

“AI allows us to prioritize the astronomical number of options and focus on the most promising ones for us to test in the lab,” says Gladstone Investigator Christina Theodoris, MD, PhD, who developed Geneformer in 2021. “This makes us much more efficient in our work and can lead us to develop treatments faster.”

Already, Theodoris has used Geneformer to point to potential treatment targets for cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that makes it harder for the heart to pump blood.

Her team used the AI model to predict which genetic changes can make diseased heart muscle cells resemble healthy ones. And when the researchers tested this unexpected prediction in the lab, they successfully restored the diseased cells’ ability to beat.

Discoveries such as this one can lead to new therapies that address the root cause of a disease, rather than just managing its symptoms. And the power of Geneformer is not restricted to heart cells or cardiomyopathy—it can tackle numerous other types of cells and diseases.

Christina Theodoris (left) created the world's first AI model, called Geneformer, that can look at and predict gene activity within individual cells. This model can identify what change in a gene is likely causing disease, and researchers can then validate the prediction in the lab. (Seen here, on the right, is David Wen, graduate student in Theodoris’s lab.)

Like many other Gladstone scientists who design novel technologies, Theodoris has made her AI model open-source, so it’s readily available to any other scientist wishing to use it—and thousands across the world are already doing so.

“We’re always excited to hear of a new academic lab or pharmaceutical company using Geneformer to predict therapeutic targets for their disease of interest,” Theodoris says. “What’s most important to us is for the model to be used broadly so it can accelerate the discovery of new treatments that can benefit patients.”

Where AI Models Meet Biotechnology

Close collaboration between the scientists who develop AI models and the researchers working in wet labs—where they conduct experiments on living cells and physical biological samples—is necessary. Not only for validating AI predictions, but also for generating the most useful data to train AI models.

“Our vision is to have the AI person and the experimental person working together from the start,” Engelhardt says. “That way, you can design cutting-edge experiments because you know there’s AI to support those experiments, and you can design cool AI because you’ll have the experimental data to feed those models. That’s leading to a real acceleration of ideas in biology right now.”

When these experts combine their ultra-specialized skillsets, they can truly push the limits of what can be accomplished in science. This is why Gladstone scientists are developing computational techniques and wet lab technologies side by side.

For instance, Pollard has joined forces with two of her colleagues, Seth Shipman, PhD, and Vijay Ramani, PhD, to test the predictions of her AI models, and continue to improve them. Shipman invented a technique to make thousands of DNA edits simultaneously in a single dish by using a bacterial immune system, called a retron. And Ramani designed a novel method to read out single DNA molecules and measure the effect of each edit on the cell and its function.

Together, these labs can now tackle fundamental questions in biology that could never be addressed before, such as what precise genetic change actually causes a given disease.

Katie Pollard and other Gladstone scientists who develop AI models are closely collaborating with researchers who conduct experiments on living cells, both to validate AI predictions in the lab and to generate the most useful data to train AI models. (On the right is Sean Whalen, principal staff research scientist in the Pollard Lab.)

These new approaches intersect with two other paradigm-shifting technologies invented by Gladstone investigators.

The first is induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell technology, discovered by Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, which enables scientists to use a blood sample from a patient carrying a disease and turn the blood cells into any other cell type they want to study. The second is CRISPR genome editing, co-invented by Jennifer Doudna, PhD, which researchers can leverage to precisely rewrite DNA and see what happens to the cell when they change or remove a gene.

Both scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize for these transformative discoveries and work with disease experts at Gladstone to develop new therapeutic solutions.

“Our discoveries are really only made possible because all these technologies are converging in one place, where we work alongside the world’s experts in specific disease areas.”

—Katie Pollard, PhD

“Our discoveries are really only made possible because all these technologies are converging in one place, where we work alongside the world’s experts in specific disease areas,” Pollard says.

Srivastava agrees this is the recipe for success.

“For the first time in history, we have access to amazing technologies in the lab that allow us to uncover deeper insights than ever before,” Srivastava says. “When we combine these tools with AI, we can finally get to the root cause of disease and contemplate not only treatments, but prevention and cures.”

Transforming the Role of a Scientist

In another Gladstone lab, AI is not only making predictions, but validating them too. In fact, a platform dubbed the “thinking microscope” can essentially design and perform its own experiments, and do it faster and cheaper than traditional methods.

The robotic microscope can induce a disease process, say for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, directly in human brain cells in the dish, and follow the cells for days or weeks at a time. Then, using a type of AI called reinforcement learning, the microscope learns from its observations and determines on its own what it should test next.

The thinking microscope—the first of its kind in the world—has attracted collaborations with major AI entities, including OpenAI, Google’s DeepMind, and Microsoft Research.

It also begs the question: if AI can do it all, where do human scientists enter the picture?

“It’s true that AI can accomplish some tasks that are superhuman—but you can’t completely remove humans from the equation.”

—Steven Finkbeiner, MD, PhD

“It’s true that AI can accomplish some tasks that are superhuman—but you can’t completely remove humans from the equation,” says Steven Finkbeiner, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Systems and Therapeutics at Gladstone and inventor of the thinking microscope. “It’s up to us to choose the problems we want AI to solve.”

Indeed, it’s important to remember that AI is not perfect. One of its weaknesses is known as hallucinations, which is when AI confidently delivers an incorrect answer to a problem. You can find such examples across the internet, such as a chatbot answering “two” when asked how many rocks a person should eat in a day.

And given that it can be difficult to understand how an AI model arrives at a prediction, a scientist’s rigor may be more crucial than ever.

Steven Finkbeiner (left) developed an AI-driven "thinking microscope" that can design and perform its own experiments. (On the right, scientist Shijie Wang is loading a plate of cells onto this microscope.)

“One advantage we have in science is that we can test in the lab many predictions made by AI,” Finkbeiner says. “That helps us build trust in our models over time, and allows us to train a better AI.”

So perhaps, the role of a scientist is simply evolving, or even becoming amplified. But it’s clear that humans should remain in the driver’s seat—at least when it comes to research.

At Gladstone, researchers are the ones with the disease expertise, the context of how the pieces fit together, and the critical ability to translate their work into medicines. When you add AI to their toolbelt, they simply get better at their jobs, and faster than ever before.

For years, conventional science has been limited to slow, linear approaches. Now, with AI, scientists are armed with an unrivaled tool for tackling the most complex problems.

“AI is going to fundamentally reshape how we study biology,” Srivastava says. “It’s going to accelerate science across the world and enable us to finally find the cures we’ve been searching for.”

Science in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Science in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

In this video, Gladstone scientists share how they used stem cells, gene editing, and AI to identify a gene driving heart defects in Down syndrome—and how reducing its levels in mice restored normal heart development, offering hope for future treatments

Gladstone Experts Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Pollard Lab Srivastava Lab AI Big Data CRISPR/Gene Editing Human Genetics Stem Cells/iPSCsMeet Gladstone: Shijie Wang

Meet Gladstone: Shijie Wang

Shijie Wang, a postdoctoral scholar in Steve Finkbeiner’s lab, uses artificial intelligence, robotics, and stem cell technologies to uncover how brain cells die in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Profile Neurological Disease Finkbeiner Lab AI Robotic MicroscopyScientists Pinpoint a Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Scientists Pinpoint a Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

After decades of mystery, Gladstone researchers identify a gene that can derail heart formation—and show that fixing it prevents the problem in mice.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Pollard Lab Srivastava Lab AI CRISPR/Gene Editing Stem Cells/iPSCs