Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

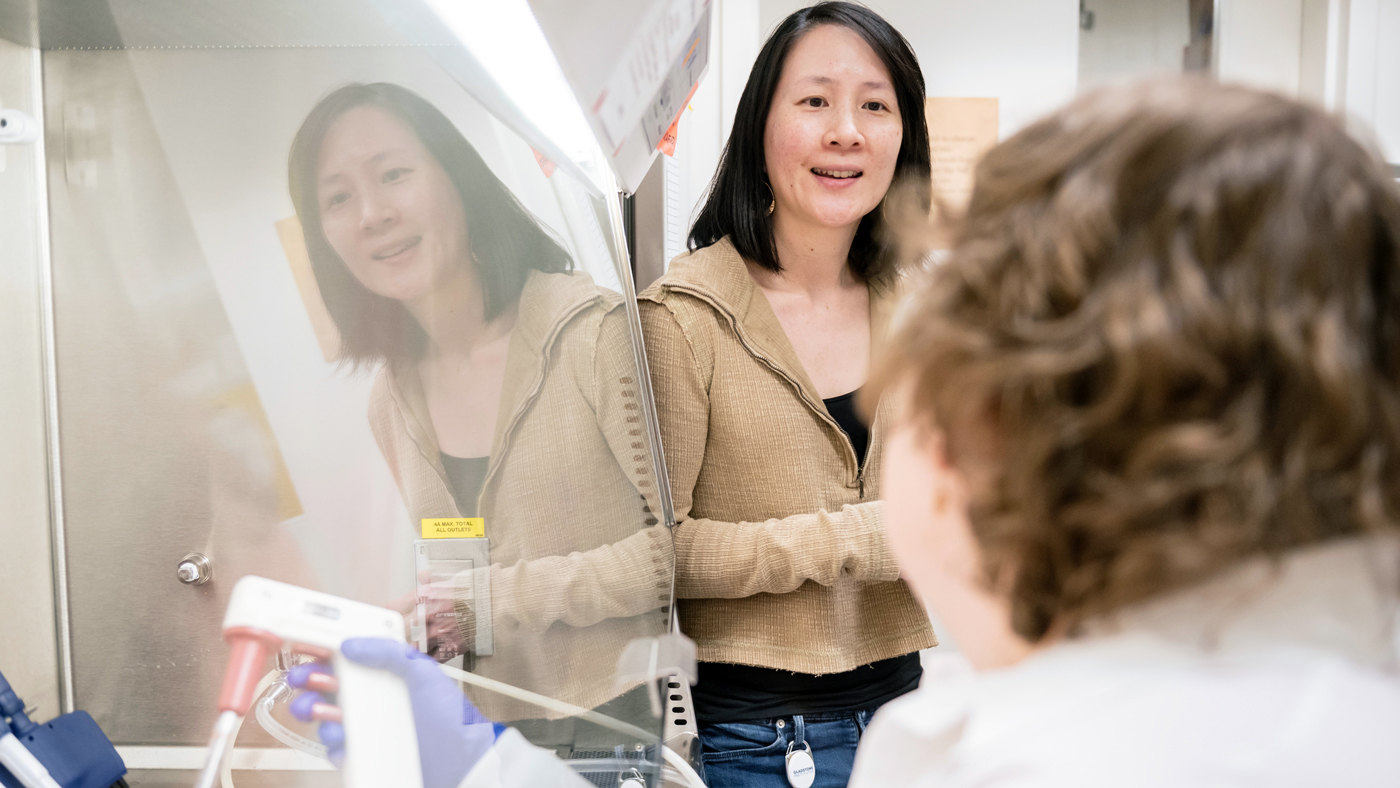

Ashley George (left) and Nadia Roan (right) helped create a new tool to understand the immune system’s inner workings when it is confronted with a virus.

In a study that vastly expands our understanding of how the immune system interacts with viruses, scientists from Gladstone Institutes have developed a detailed map of the body’s natural defenses against one of the most vexing viral threats: HIV.

Their findings, which appear in the journal Cell Reports, paint a comprehensive picture of the levels of 19 different viral sensors and receptors—across all kinds of immune cells, including those susceptible to HIV infection—that can respond to HIV.

And although the team focused on HIV for the study, they discovered fundamental insights into how different immune cells can sense and restrict pathogens in unique ways. These findings can have implications for understanding the immune response to diverse viruses and microbes, and even autoimmunity, says Gladstone Investigator Nadia Roan, PhD, senior author of the new paper.

Roan (left) and her team developed a tool that reveals how individual immune cells sense and respond to different pathogens.

“We developed a tool that allowed us to simultaneously map out—at the single cell level—the levels of a myriad of different viral sensors and receptors, which reveals how different immune cell types divvy up the jobs of sensing different types of microbial products, including those derived from invading viruses,” Roan says.

Here, first author Ashley George, PhD, of the Roan Lab, shares important takeaways from the study.

What was the big question you initially set out to answer with this research?

The whole project started with our desire to more fully understand the many ways individual immune cells are sensing and responding to disease-causing viruses, with a focus on HIV.

Surprisingly, there’s very little data about how these factors are distributed between different cell types across the human body—and part of the reason for that is there aren’t great tools to capture those data. For this study, we had to create an entirely new tool, which we call VISOR-CyTOF.

What did the tool enable you to see?

Among some of our key discoveries, we were able to learn which immune cells are better equipped to fight HIV, which are more vulnerable, and how the virus might be able to hide in some cells.

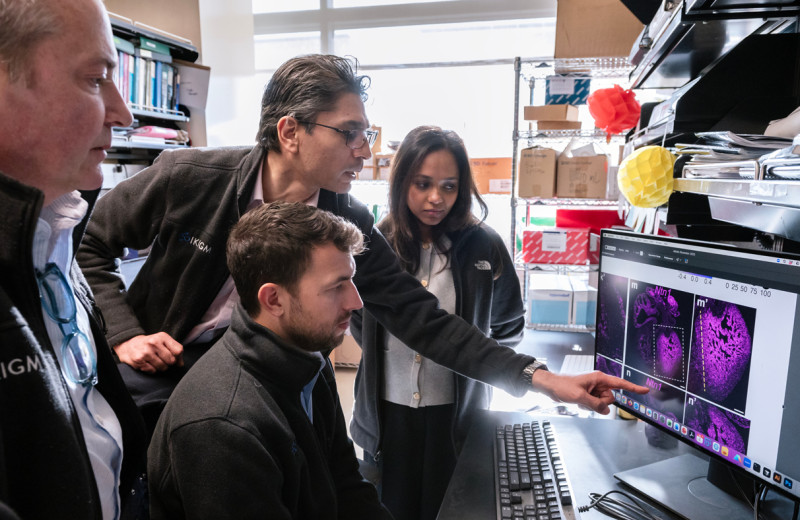

Using the new tool she helped create, George was able to learn which immune cells are better equipped to fight HIV, and which are more vulnerable. The tool could also be used to study other viruses and autoimmune diseases.

We also saw how some immune cells harbor far more virus detectors than others. For example, myeloid cells have a very high level—which is logical because these immune cells are known to initiate immune responses and are uncommon targets for HIV during early infection. In contrast, B cells, which are important later in the immune response, expressed a far lower number.

We also studied how cells behave in different parts of the body. Cells in mucosal organs, like the gut and lungs, tended to express higher levels. This intuitively makes sense because these organs are more likely to be exposed to viruses from the outside world and they have their own microbiomes, which likely plays a role.

One thing that makes this study so unique is that you examined cells from real people rather than cell lines. What extra value did that bring?

We were fortunate to work with the Last Gift program at UC San Diego, through which end-of-life individuals with HIV donate tissues post-mortem to advance discovery. For researchers, access to such tissue is extremely rare. It allowed us to really look deeply at different immune cells and organ systems throughout the body, with findings that are far more relevant than if we were looking at cells from animals or at cell lines.

We also used cells from a blood bank and exposed those healthy cells to HIV to see how they respond. These studies, where we could control the amount of viral replication and specifically identify HIV-infected cells, nicely complemented our Last Gift analyses.

Through this work, your team made many important discoveries for HIV. But how can the findings be applied more broadly?

The ways that immune cells detect and block HIV are common across many types of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and influenza, and can be studied further with VISOR-CyTOF. The technology we developed can also be easily adapted to other pathogens or cells of interest.

Our findings may also be valuable in the area of autoimmune diseases, where the immune system attacks healthy tissue. Sometimes in these conditions, viral sensors go awry and can’t distinguish between self and non-self. We could use our technology to identify exactly what mechanisms are misfiring; that level of detail can be valuable for developing targeted therapies.

Featured Experts

Gladstone NOW: The Campaign

Join Us On The Journey

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau LabGene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Gene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Scientists at Gladstone show the new method could treat the majority of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Conklin Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingGenomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Genomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Findings of the new study in Nature could streamline scientific discovery and accelerate drug development.

News Release Research (Publication) Marson Lab Genomics Genomic Immunology