Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

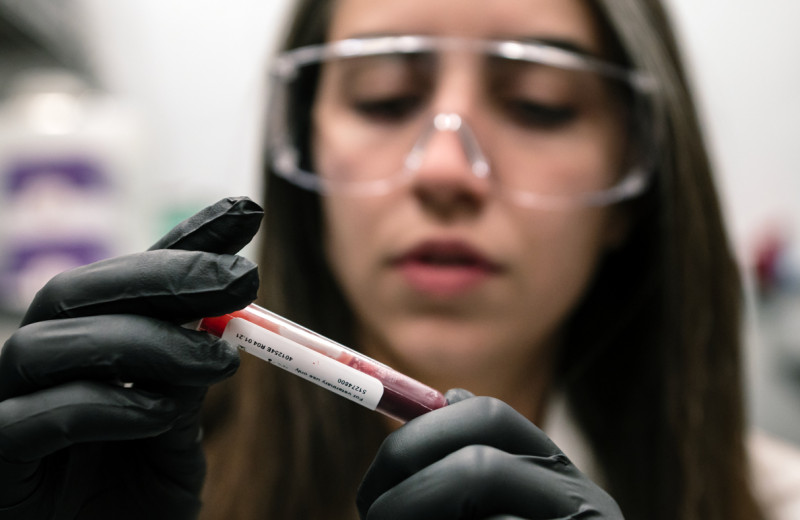

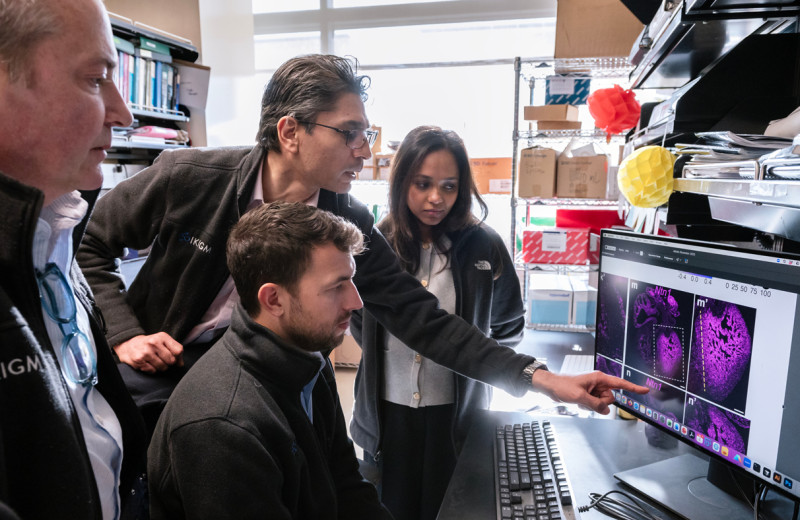

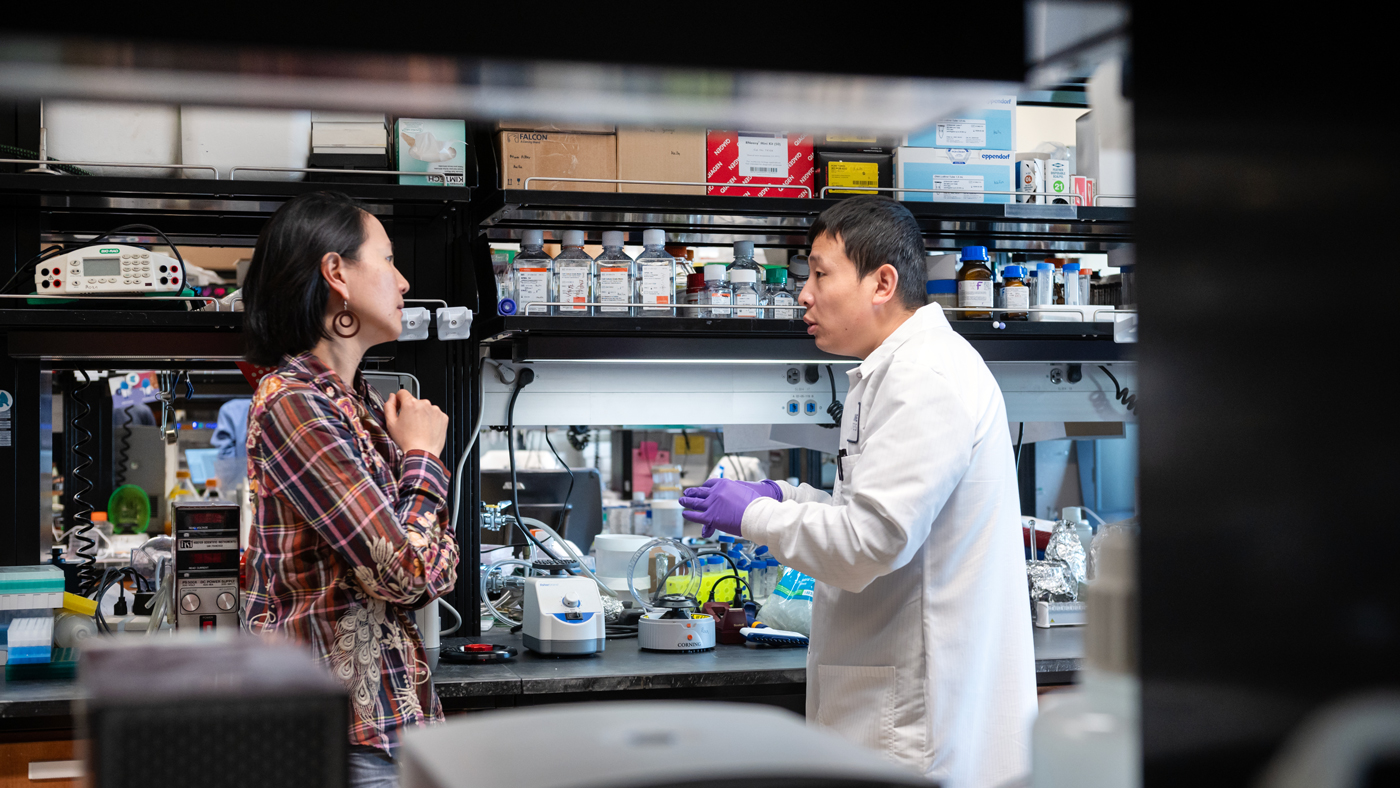

A team of scientists—including Kailin Yin (left) and Nadia Roan (right)—found that pregnant and lactating women have strong immune defenses to COVID-19, and identified key benefits that could guide future vaccine design.

Pregnancy is fundamental to our very existence. Yet, surprisingly, not much is known about how a pregnant woman’s immune system responds to a virus or vaccine—or how it might differ from when they’re not pregnant.

And even less is known about a mother’s immunity during lactation.

In a new study published in the journal JCI Insight, scientists at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco (UCSF) shed light on these mysteries. They uncovered new information about how pregnancy and breastfeeding shape immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection.

“This research could eventually lead to the design of better vaccines, not just for pregnant and lactating individuals, but for everyone.”

The research not only demonstrates that COVID-19 vaccines elicit just as strong of an immune response in pregnancy, but points to unique immunological benefits of being vaccinated while pregnant. Additionally, the team found that lactating women responded a bit differently to COVID-19 infection or vaccination, in a way that likely benefits infants.

“Our findings help us better understand immunity during pregnancy and lactation, both in the context of COVID-19 and more broadly,” says Nadia Roan, PhD, a senior investigator and virus expert at Gladstone who helped lead the study. “This research could eventually lead to the design of better vaccines, not just for pregnant and lactating individuals, but for everyone.”

A Unique Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic presented the scientists with a unique opportunity. For the first time, they could analyze the immune response of a large number of people to a virus in a relatively controlled way.

“The timing was key: we had a brand-new virus that everyone was being exposed to for the first time, at essentially the same time,” Roan explains.

For the study, Roan and her colleagues compared three groups of individuals: pregnant, breastfeeding, and women who were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. The team looked specifically at immune responses involving T cells—important soldiers in the body’s defense force—and the production of antibodies, which act like shields to fight off invading viruses.

Findings from the new study shed light on what happens immunologically during pregnancy and lactation, and will help inform future vaccine strategies for COVID-19 and other viruses. Seen here are Nadia Roan (left) and Kailin Yin (right), the study's first author.

In the three groups of study participants, researchers focused on immune responses after individuals completed a three-dose series of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, like the ones from Pfizer or Moderna. Some people enrolled in the study also experienced a so-called “breakthrough infection,” which means they tested positive for COVID-19 after receiving a full vaccine series.

Overall, the scientists found that the total amount of T cells and antibodies produced by the body to fight off the virus was similar across individuals, showing that vaccines trigger a robust immune response in all three groups.

“It’s reassuring to confirm that pregnant women don’t mount a weaker response than others, especially because we know they’re a vulnerable group when it comes to infectious diseases,” says Stephanie Gaw, MD, PhD, an obstetrician-gynecologist at UCSF specializing in high-risk pregnancies, who helped lead the study.

Longer-Lived Immunity

But the scientists also found some key differences.

To explore the nuances of each group’s immune response, the team used a method called CyTOF, which can analyze individual cells in a blood or tissue sample and provide details on the role they play in immunity and how they might differ from one sample to another.

While the total number of T cells recognizing SARS-CoV-2 was similar, the researchers found the cells behaved and looked differently for each group.

For instance, women who were vaccinated during pregnancy seemed to produce more “stem-like” T cells—a type of T cell thought to be long-lasting and capable of generating more immune cells when needed.

“This suggests that, for pregnant women, vaccine-elicited T cells may persist for longer and offer more durable protection over time,” Gaw says. “If we can better understand how to elicit these same cells in non-pregnant individuals, we could potentially improve future vaccines by making their effects last longer.”

Lactation Stimulates Mucosal Immunity

In women who were vaccinated while breastfeeding, the researchers showed that T cells circulating in the blood overall showed signs of being less activated, or less ready to fight, than blood T cells from the other groups.

While they didn’t directly study T cells in breast milk, the scientists believe—based on prior studies—that activated T cells in breastfeeding women may be moving out of the blood and going to the mammary glands.

“We know that maternal T cells, particularly those important for fighting off infections, get transferred to the infant through the milk,” says Mary Prahl, MD, a clinician-scientist and expert in maternal-child immunology at UCSF who helped lead the study. “This could be the body’s way of offering protective immunity to the nursing infant through breast milk.”

Breastfeeding women who had experienced a breakthrough infection also showed a significant increase in mucosal antibodies, a type of antibody found in the lining of the nose, throat, gut, or milk ducts.

This increase might be another way of passing on protection to the baby, since mucosal antibodies are one of the most important antibodies transferred to the infant in breast milk.

“Until now, we didn’t really know if breastfeeding women would have the same immune response as those who are neither pregnant nor lactating. Now we know they’re different.”

“If we can better understand how to boost this specific kind of antibody, we may eventually be able to design better mucosal vaccines,” Roan says. “This would reduce the need for regular vaccine boosters—like the ones we get for flu or COVID—by extending our mucosal immunity and preventing infection through the nose and throat.”

The study also underscores the importance of research focused on women’s health, which is often understudied.

“Together, our findings confirm that lactation is a unique immunological state,” Prahl says. “Until now, we didn’t really know if breastfeeding women would have the same immune response as those who are neither pregnant nor lactating. Now we know they’re different.”

Pregnancy Increases Vulnerability to Infection

Among pregnant women with breakthrough infections, the researchers found a general decrease in specific types of activated T cells in the blood, which could make pregnant women more vulnerable to infections than other groups.

This decrease, they suggest, might explain the increased risk of severe COVID-19 seen in pregnancy.

“We’re just at the beginning,” Roan says. “Our study sets the stage for understanding what happens immunologically during human pregnancy and lactation. The knowledge we gain will help inform future vaccine strategies, particularly those tailored to protect pregnant and breastfeeding women.”

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About the Study

The paper, “Pregnancy and lactation induce distinct immune responses to COVID-19 booster vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection,” was published in the journal JCI Insight on July 22, 2025.

The authors are Kailin Yin, Xiaoyu Luo, Jason Neidleman, and Nadia Roan of Gladstone; and Lin Li, Arianna G. Cassidy, Yarden Golan, Nida Ozarslan, Christine Y. Lin, Unurzul Jigmeddagva, Mikias Ilala, Megan A. Chidboy, Mary Prahl, and Stephanie L. Gaw of UCSF.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P50HD112034, R01HD111582, R01HD112339, K08AI141728, K24AI188458, and K23AI127886), the Marino Family Foundation, the Van Auken Private Foundation, David Henke, Pamela and Edward Taft, the Krzyzewski Family, and The James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Featured Experts

Gladstone NOW: The Campaign

Join Us On The Journey

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabRed Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

Red Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

New study shows red blood cells act as hidden glucose sponges in low-oxygen conditions, explaining why people living at high altitude have lower diabetes rates and pointing toward new treatments.

News Release Research (Publication) Diabetes Jain LabDisrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau Lab