Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

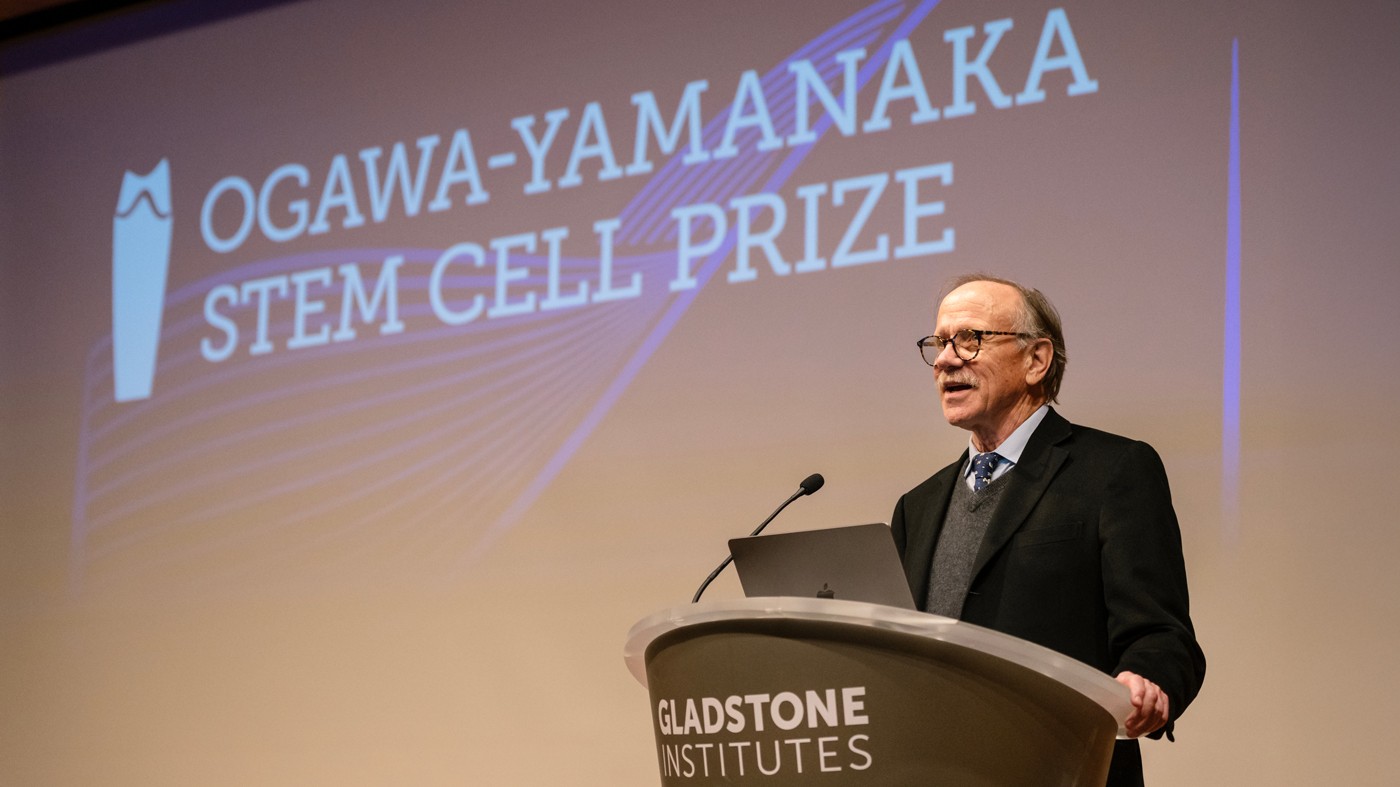

Rusty Gage, recipient of the 2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, made landmark discoveries that fundamentally shifted the field of neuroscience.

In 1998, neuroscientist Rusty Gage, PhD, redefined how we think about the brain. At the time, scientific dogma held that once a person’s brain finishes developing, it possesses all the neurons it will ever have. And while some of the cells might grow new connections over time, their number will only ever drop.

But Gage and his team upended that notion with their report that the human hippocampus—the part of the brain where memories form—continues to add new neurons throughout adulthood.

“It was a big surprise,” says Gage, a professor in the Laboratory of Genetics at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, where he also serves as the Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease. “The adult brain is far more adaptable than we thought it was.”

That discovery was just the first of several Gage-led projects that would fundamentally shift the field of neuroscience. Notably, he and his lab members pioneered novel methods for reprogramming human cells in order to study age-related neurological disorders, setting the stage for better treatments.

“The adult brain is far more adaptable than we thought it was.”

Now, his combined contributions have earned Gage the 2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, awarded by Gladstone Institutes and Cell Press.

“Gage is one of those rare figures who has truly altered the trajectory of his field,” says Deepak Srivastava, MD, president of Gladstone and chair of the prize’s selection committee. “His lifelong curiosity and his gifts as a leader and mentor continue to guide us toward promising new treatments for people with Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other neurological conditions.”

The Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize was established in 2015 by a philanthropic gift from Hiro and Betty Ogawa, and is now supported by their sons, Marcus and Andrew Ogawa. It celebrates scientists who advance the field of translational regenerative medicine, in particular through the use of cellular reprogramming.

As the winner of the 2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, Gage was honored during a reception held by Gladstone in December 2024. Left to right: Deepak Srivastava, Chika Yamanaka, Shinya Yamanaka, Marcus Ogawa, Athena Ogawa, Rusty Gage, and Mary Lynn Gage.

The prize also honors Gladstone Investigator and Nobel Prize winner Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, who himself changed the landscape of regenerative medicine with his technique for reprogramming adult skin cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which can then be grown into nearly any other type of human cell.

On December 3, Gladstone hosted a ceremony to present Gage with the award, alongside an unrestricted prize of $150,000.

“I have so much admiration for Shinya, Hiro, and the past prize winners as friends and colleagues,” says Gage, who was president of the Salk Institute from 2018 to 2024. “So to now be a recipient myself is quite an honor.”

Captivated by Science

For the past 40 years, Gage has called San Diego, California, home. His childhood, however, was far less stationary.

“My dad was a Navy pilot, so we moved around to lots of different places; Hawaii, San Francisco, Virginia, outside of Chicago—all before I was 8,” Gage says. “Then we lived in Naples, Italy, for a few years before my dad retired from the Navy and we moved to Frankfurt, Germany.”

Gage returned to Italy to attend a boarding high school in Rome. There, he developed an interest in philosophy and considered becoming a playwright.

“But my older sister, who became a very successful research psychologist, kept telling me, ‘No, no, you’ve got to be a scientist,’ sending me books and articles, and being a real champion for me to do science,” he says.

One of the authors she introduced him to was Isaac Asimov, a biochemist who wrote many nonfiction science books in addition to his iconic fiction. “His nonfiction just captivated me and made science come alive,” Gage says. “That was an important early influence.”

Gage, seen here presenting his research during the Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize ceremony, made important discoveries that redefined how we think about the human brain and developed new methods for reprogramming human cells to study neurological disorders.

By the time he started college in 1968 at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Gage was hooked on science. There, he worked in a brain research laboratory, and after graduating, he earned a PhD in neuroscience from Johns Hopkins University. He then took a position at Texas Christian University, followed by another at Lund University in Sweden to work with neuroscientist Anders Björklund, MD, PhD.

In 1985, Gage left Sweden to join the faculty of the University of California, San Diego. He was recruited in 1995 to co-lead a new laboratory at the nearby Salk Institute, which was then led by president Francis Crick, PhD, famous for his role in determining the molecular structure of DNA.

“Francis told me that I was recruited not because of any particular discovery I’d made, but because of my overall scientific approach, and that if I wanted to switch to, say, plant science, I was welcome to,” Gage says. “I’m fortunate to have landed in such a rich environment of curiosity-driven science without any barriers.”

The Brain’s Unexpected Flexibility

Three years after joining the Salk Institute, Gage made headlines with his revelation that stem cells in the adult human brain can give rise to new neurons. In subsequent years, his team worked out many of the molecular mechanisms underlying the process, as well as its ramifications for learning and memory.

“These new neurons appear to help us integrate new information and distinguish between closely related experiences and memories,” Gage says. “We’ve also found that, as we get older, our ability to grow new neurons declines, but we can mitigate that decline through physical activity, diet, and learning and experiencing new things.”

“Across the field, people are using so many creative approaches to reconstruct elements of the human brain in all its complexity, enabling us to look at all the interacting effects of experimental therapies.”

Later, while studying adult neurogenesis (the growth of new neurons), Gage and his team made another radical discovery.

They showed that, when one cell divides into two cells during neurogenesis, small pieces of DNA called mobile elements can jump from one location to another in the genome. That means that two adjacent neurons in the brain can hold two sets of genetic material that are even more distinct than previously thought possible.

“Our evidence also now suggests that dysregulation of the mobile-element jumping process might contribute to brain disorders like bipolar disease, schizophrenia, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease,” Gage says.

Today, Gage’s lab is applying a suite of advanced techniques, including live imaging of individual neurons, to explore neurogenesis in the context of the aging brain. This work could lead to new approaches for treating age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative conditions that were once believed to be irreversible, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The Cellular Reprogramming Revolution

In addition to studying stem cells in the brain, Gage has also long studied stem cells in a dish, as he models and investigates various neurological diseases in the lab. During his first decade at the Salk Institute, the best option was to use embryo-derived lines of stem cells, which can be coaxed into becoming most types of cells in the human body, including neurons.

However, while such an approach can reveal exciting insights into disease, the scientific and therapeutic potential of embryonic stem cells is limited because they cannot exactly match the genetic profile of an individual patient.

That is why, in 2006, the field transformed when Yamanaka announced his method for reprogramming adult skin cells into iPS cells, which retain the patient’s genome and can grow into other types of cells.

“Many people around the world were trying to figure out how to do this, and we were too,” Gage says. “But what set Yamanaka’s approach apart was how reproducible, how reliable, it was. And once it was in everybody’s hands, the floodgates were open; it revolutionized disease modeling.”

Gage (left) was presented with the 2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize by Deepak Srivastava (right), president of Gladstone and chair of the prize’s selection committee.

Gage was at the forefront of this new era of regenerative science. In one landmark project, published in 2011, he and his colleagues grew neurons from iPS cells generated from skin cells that had been donated by people with schizophrenia. They found that, in early developmental stages, these neurons already showed signs of dysfunction, suggesting novel possibilities for the early detection and treatment of schizophrenia.

In a 2015 study, his team applied lithium to neurons generated from the skin cells of people with bipolar disorder. Lithium is a mainstay treatment that eases symptoms for some bipolar patients but not for others. The researchers found that they could predict whether a given patient would benefit from it based on how the neurons grown from their skin cells reacted to lithium in the lab.

“It was incredible to see real people’s clinical features reproduced in a dish,” Gage says. “Across diseases, these kinds of experiments can be translated into tests that could inform individual treatment decisions.”

Importantly, alongside his work with iPS cells, Gage innovated on Yamanaka’s approach by developing methods for directly producing specific types of neurons from a person’s skin cells, bypassing the iPS stage and retaining molecular signs of the person’s age. With these novel advancements, his team developed some of the first “disease-in-a-dish” models for studying such age-related conditions as Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Today, Gage’s lab continues to explore the growth of new neurons in the context of the aging brain—work that could lead to new ways of treating neurodegenerative conditions that were once believed to be irreversible, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Gage’s lab has also pioneered methods for using iPS cells to grow patient-specific brain organoids—tiny, three-dimensional, brain-like structures that mimic some of the features of the human brain. Brain organoids can be used in the lab to test treatments for neurological disorders, and they hold future potential for transplantation to treat a person’s damaged brain.

“We were finding that when brain organoids get above about 3 millimeters in diameter, they begin to die because they lack blood vessels to deliver nutrients to their core,” Gage says. “Then, I recalled a technique I helped develop in Sweden in the 1980s for grafting cells into a certain area of the mouse brain that is very rich in blood vessels.”

Inspired by that earlier work, he figured out how to transplant human iPS-based brain organoids into the vessel-rich part of the mouse brain. There, the organoids stay healthy for longer time periods. They also show signs of increased complexity, hinting that they may more closely mimic human brain functions and could therefore be better models for studying the human brain.

An Open Field for Discovery

With more than 900 publications under his belt and a reputation for being a dedicated mentor, Gage is one of the most influential figures in neuroscience. He credits much of his success to the many students and staff members who have shared his lab bench, many of whom went on to shape the field in their own right—including the inaugural recipient of the Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, Masayo Takahashi, MD, PhD.

“I am fortunate to have had such high-quality researchers come through my lab and contribute to discoveries that otherwise would not have been possible,” Gage says. “My receiving this prize really reflects on all of their incredible work.”

“We’re in this very exciting middle game where there really are no rules, and it’s just an open field to do whatever imaginative thing you can get done.”

In addition to his academic positions, Gage has served as president of the Society for Neuroscience and the International Society for Stem Cell Research, as co-director of the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind, and on the scientific advisory boards of several disease foundations. Following a five-year term as president of the Salk Institute, he has embraced returning to full-time work in his lab.

Today, his lab continues to generate discovery after discovery, harnessing and advancing the latest techniques for understanding the brain.

“Right now, I’m particularly excited about the potential for organoids to better represent tissues of interest,” Gage says. “Across the field, people are using so many creative approaches to reconstruct elements of the human brain in all its complexity, enabling us to look at all the interacting effects of experimental therapies.”

He adds, “We’re in this very exciting middle game where there really are no rules, and it’s just an open field to do whatever imaginative thing you can get done.”

A Sculptor of Modern Regenerative Medicine

A Sculptor of Modern Regenerative Medicine

Among his myriad accomplishments, Rudolf Jaenisch—winner of the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize—was the first to demonstrate the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells to treat disease.

Awards Ogawa Stem Cell Prize Profile Regenerative Medicine Stem Cells/iPSCsSix Gladstone Scientists Named Among World’s Most Highly Cited Researchers

Six Gladstone Scientists Named Among World’s Most Highly Cited Researchers

The featured scientists include global leaders in gene editing, data science, and immunology.

Awards News Release Corces Lab Doudna Lab Marson Lab Pollard Lab Ye LabBringing Modern Science to Vitamin Biology: Isha Jain Wins NIH Transformative Research Award

Bringing Modern Science to Vitamin Biology: Isha Jain Wins NIH Transformative Research Award

Leveraging modern scientific tools and techniques, Jain intends to transform our understanding of the critical roles that vitamins play in health and disease.

Awards News Release Cardiovascular Disease Jain Lab Metabolism