Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Gladstone Senior Investigator Dr. Todd McDevitt discovered the first-ever way to regrow bone tissue using the protein signals produced by stem cells. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow]

Scientists have discovered a way to regrow bone tissue using the protein signals produced by stem cells. This technology could help treat victims who have experienced major trauma to a limb, like soldiers wounded in combat or casualties of a natural disaster. The new method improves on older therapies by providing a sustainable source for fresh tissue and reducing the risk of tumor formation that can arise with stem cell transplants.

The new study, published in Scientific Reports, is is the first to extract the necessary bone-producing growth factors from stem cells and to show that these proteins are sufficient to create new bone. The stem cell-based approach was as effective as the current standard treatment in terms of the amount of bone created.

“This proof-of-principle work establishes a novel bone formation therapy that exploits the regenerative potential of stem cells,” says senior author Todd McDevitt, PhD, a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institutes. “With this technique, we can produce new tissue that is completely stem cell-derived and that performs similarly with the gold standard in the field.”

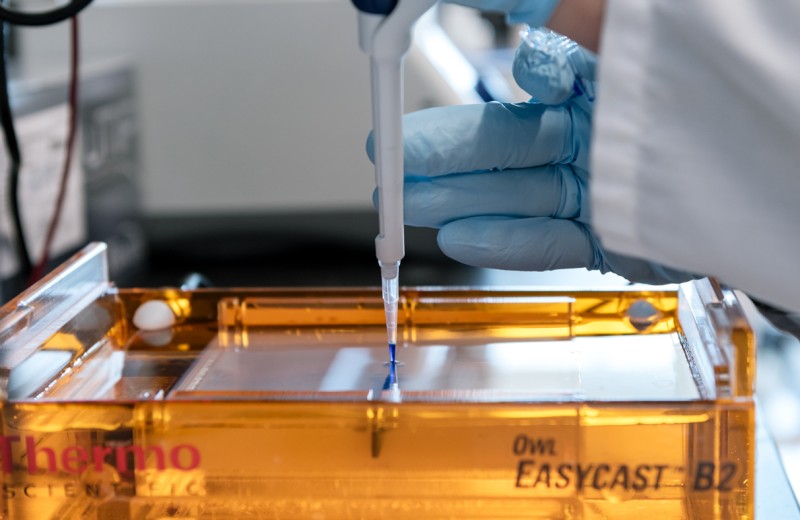

Instead of using stem cells themselves, the scientists extracted the proteins that the cells secrete—such as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)—in order to harness their regenerative power. To do so, the researchers first treated stem cells with a chemical that helped coax them into early bone cells. Next, they mined the essential factors produced by the cells that send the signal to regenerate new tissue. Finally, the researchers delivered these proteins into mouse muscle tissue to facilitate new bone growth.

The current standard method involves grinding up old bones in order to extract the proteins and growth factors needed to stimulate new bone growth—a substance dubbed demineralized bone matrix (DBM). However, this approach has significant restrictions as it relies on bones taken from cadavers, which can be highly variable in terms of tissue quality and how much of the necessary signals they still produce. Moreover, as is the problem in organ donation, cadaver tissue is not always available.

“These limitations motivate the need for more consistent and reproducible source material for tissue regeneration,” says Dr. McDevitt, who conducted the research while he was a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “As a renewable resource that is both scalable and consistent in manufacturing, pluripotent stem cells are an ideal solution.”

Mini-Livers on a Chip

Mini-Livers on a Chip

A new platform designed by Gladstone scientists for studying how the immune system responds to hepatitis C virus could speed the hunt for a vaccine

News Release Research (Publication) Hepatitis C Infectious Disease McDevitt Lab Ott Lab OrganoidsIt Takes Guts to Make a Heart

It Takes Guts to Make a Heart

Gladstone scientists create novel organoids that open new doors for understanding crosstalk between tissues during human development

News Release Research (Publication) Cardiovascular Disease McDevitt Lab OrganoidsHow Do Developing Spinal Cords Choose “Heads” or “Tails”?

How Do Developing Spinal Cords Choose “Heads” or “Tails”?

A new human organoid developed by Gladstone scientists mimics one of the key steps in early embryonic development

News Release Research (Publication) Cardiovascular Disease McDevitt Lab CRISPR/Gene Editing Stem Cells/iPSCs