Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

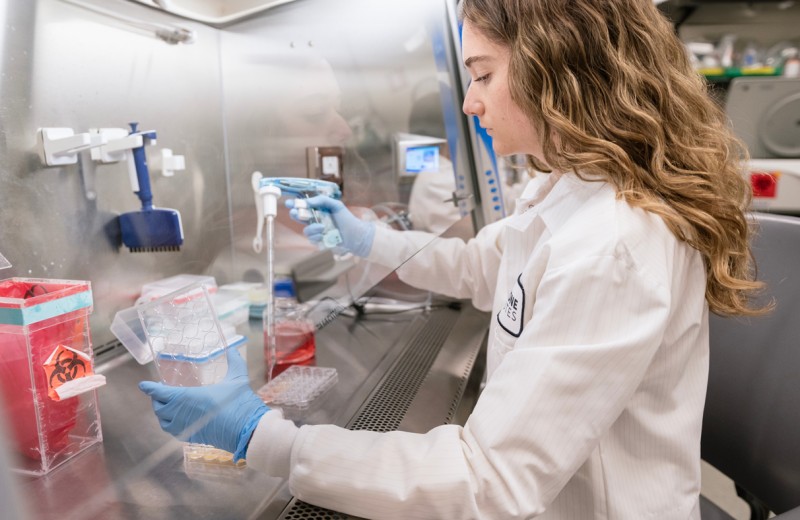

Drs. Kumar, Krogan, Ott, and Verschueren are studying the interactions between viruses and cells to illuminate common weak points in human biology and identify new targets for treatments. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow]

Back-to-back studies from researchers at the Gladstone Institutes have exposed new battle tactics employed by two deadly viruses: hepatitis C (HCV) and the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Published in the January 22 issue of Molecular Cell, the investigators created full protein interaction maps—interactomes—of where the viruses come into contact with the host proteins during the course of infection. Through these protein interactions, the scientists not only gained insight into the viruses, they also uncovered a common set of host proteins that are targeted by various infections. Their results suggest that these proteins and the cellular processes they govern are the most crucial—in effect, the collective Achilles heel—for both the human body and its viral invaders.

“Viruses are fantastic tools for shedding new light on human biology,” says Nevan Krogan, PhD, a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institutes and a corresponding author on both papers. “Viruses are relatively simple organisms—often they only have about 10-20 genes—but they wreak havoc on our system by targeting key proteins and essential functional pathways in every major biological process. This gives us great insight into what the critical mechanisms are that are being hijacked during infection, and it helps us to develop new strategies for preventing or stemming disease.”

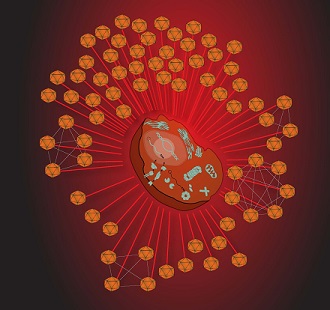

A network of viral invaders about to attack a human host cell. [Image: Mike Shales]

In the first study, Dr. Krogan, who is also a professor of cellular and molecular pharmacology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and director of the UCSF branch of QB3, partnered with Gladstone senior investigator Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, to map the interaction between the proteins in HCV and those in the human liver cells that HCV infects. This resulted in over 5,000 virus-host protein-to-protein interactions, which the investigators narrowed down to 139 key connections that are necessary for HCV infection, involving all 10 HCV proteins and 133 proteins in the host liver cells.

Although patients have benefited from numerous advancements in the treatment of HCV, how the virus damages the liver remains unknown. The HCV interactome map, led by first authors Holly Ramage, PhD, and G. Renuka Kumar, PhD, may help on this front.

“There’s a lot we still don’t know about HCV, like how it infects the cell, what processes it disrupts, and why it’s so harmful to the body,” explains Dr. Ott, who is also a professor of medicine at UCSF. “The protein interactome offers us an unbiased and global view of how the virus is affecting the infected cells, and this can help us to start answering a lot of the important questions. Ultimately, this information may direct us to new leads for preventative treatments for associated liver pathologies, like fibrosis and cancer.”

By removing the interacting host proteins from the cell one at a time, the researchers were able to determine what their functional contribution was in the infection process: whether the host proteins were hijacked by the virus and used to spread infection, or whether they were part of a defense mechanism against the virus. This revealed a new critical host mechanism that HCV inactivates and usurps to support its own survival and replication.

The second study, a collaboration between Dr. Krogan and Britt Glaunsinger, PhD, at UC Berkeley, resulted in the largest host-virus protein interactome ever created using the herpesvirus KSHV. This resulted in a staggering 50,000 virus-host protein interactions, approximately 500 of which appeared to be involved in viral infection.

KSHV causes Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer that commonly occurs in patients with AIDS, so the researchers were especially interested in where the interaction points for KSHV overlapped with those for either HIV or cancer. The researchers discovered that latent proteins in KSHV—those that are associated with the virus’s active state—manipulate the same genes that are mutated in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Additionally, a significant overlap surfaced between host proteins that interacted with both KSHV and HIV. The intersection between the two viruses suggests that these host-protein interaction points are especially important and therefore may be ideal targets for new, more generalized therapeutics to stop infection.

“Designing a treatment that targets some of these cellular mechanisms may offer a silver bullet to fight disease—not just for KSHV or HCV, but for any number of viral infections,” says Dr. Krogan. “By identifying the most important cellular components that viruses hijack and re-wires, we can more intelligently design drugs that target the virus’s weak points and where it interacts with the host.”

Could This Molecule Be ‘Checkmate’ for Coronaviruses?

Could This Molecule Be ‘Checkmate’ for Coronaviruses?

Scientists develop powerful drug candidates that could head off future coronavirus pandemics.

News Release Research (Publication) COVID-19 Infectious Disease Krogan Lab Ott LabUnderstanding How the Immune System Switches Between Rest and Action

Understanding How the Immune System Switches Between Rest and Action

Scientists at Gladstone and UCSF discover how one protein controls the behavior of immune cells, with potential applications for treating cancer and autoimmune conditions.

News Release Research (Publication) Autoimmune Diseases Cancer Genomic Immunology Krogan Lab Marson Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingFive Gladstone Scientists Ranked Among Most Highly Cited Researchers in the World

Five Gladstone Scientists Ranked Among Most Highly Cited Researchers in the World

The featured scientists include global leaders in gene editing, systems biology, AI, and immunology.

Awards News Release Doudna Lab Krogan Lab Marson Lab Pollard Lab Ye Lab