Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Scientists have shown that cloth masks filter out 60 to 85 percent of the incoming viral particles.

When COVID-19 started spreading around the globe earlier this year, we knew very little about it. As scientists furiously study this viral infection and develop potential treatments and vaccines, we continue to learn new facts every day that inform public health guidelines and decision-making, such as when to shelter-in-place and when to safely reopen communities.

With so much new data made available so quickly, it’s easy to lose track or become confused, not knowing what information to trust. It’s also easy to lose an argument with an acquaintance who claims masks are useless.

So, let’s clarify a few common misconceptions currently circulating through news outlets and social media.

1. At the beginning of this crisis, we were told not to wear masks. What has changed?

Initial directives from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that it was not helpful to wear a mask. These instructions were based on the previous outbreaks of SARS and MERS, for which face masks offered little protection because people infected with these viruses were not shedding virus before they became ill.

However, scientists soon discovered that COVID-19 is different because individuals can be infectious, yet show no signs of being sick. In fact, between 40 to 45 percent of people infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are asymptomatic. During the period of infection, these individuals are feeling well but actively shedding virus and potentially passing it to others. This long period of unrecognized asymptomatic infection causes the disease to quickly spread through families, workplaces, and communities.

Recently, researchers also confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 can not only spread through respiratory droplets, but also through tiny aerosols, which are 10 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. Aerosols can also travel farther than 6 feet in distance, so they can reach people even when they are keeping appropriate physical distancing.

We now know that covering your nose and mouth with a cloth or surgical mask is very effective in preventing the spread of the virus by capturing both respiratory droplets and aerosols. Take a recent case study of two hair stylists in Missouri who interacted with 139 clients before realizing they had COVID-19. Because they and their clients all wore face masks, none of the 139 clients became sick, despite both stylists being actively infected.

“Wearing a mask is now recognized to offer two forms of protection,” explains Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology. “The mask prevents you from infecting others in case you are asymptomatically infected. And it also protects you by reducing your chances of becoming infected.”

While not as effective as N95 masks worn by health care workers in close contact with patients, scientists have shown that cloth masks filter out 60 to 85 percent of the incoming viral particles. And, because the amount of virus you are infected with often determines the seriousness of your infection, masking can make it more likely that if you become infected, you will have an asymptomatic or mild form of COVID-19.

2. I’m a young and healthy adult, so the public health guidelines don’t apply to me, right?

Much of the focus at the outset of this pandemic was on raising awareness among high-risk individuals—mainly those over the age of 65—to prevent them from becoming infected. This led some younger generations to take a more cavalier approach to the virus.

But the coronavirus does not discriminate based on age. Even if you’re a young and healthy adult, you can become infected and suffer very serious symptoms.

“We’re seeing an increasing number of younger people getting infected and being hospitalized for serious illness,” says virologist Warner Greene, MD, PhD, a senior investigator at Gladstone Institutes. “Many are on ventilators in the intensive care unit.”

Some people find masks obtrusive. Others may even think a mask makes them look weak. But not liking masks does not make them invincible.

As the average age of new cases in some parts of the country is becoming lower by 10 to 15 years, it’s crucial for young people to realize that face masks can protect them as much as anyone.

They should remember that masking will also protect their friends and loved ones who might be at high risk of becoming infected. By following public health guidelines, they can help free up hospital beds and ventilators that are needed to prevent COVID-19 related deaths.

3. Will a vaccine be effective if coronavirus antibodies don’t stay in our body for a long time?

Recent reports have indicated that coronavirus antibodies disappear from the bloodstream a few months after infection. As a result, some people are worried this could mean that the human body cannot develop lasting immunity against the virus, and that vaccines might not be effective.

“We need to remember that vaccines don’t prevent the infection, they prevent the disease,” says Greene. “What’s important is not how long the antibodies last, but how well you can remobilize your immune system to face a Sars-CoV-2 infection and prevent it from progressing to a serious disease.”

Vaccines are developed to set up a memory response by coaxing the immune system to create and store long-lived memory B cells, which are then called upon if you become infected by the virus. These memory B cells may fade over time, but that would mean requiring booster vaccines at certain time intervals to stay protected.

The other important element of our immune response are the T cells that actually fight off the invading virus. The vaccines that are most likely to have the greatest effect are ones that combine the ability to induce both B and T cells to respond to the virus.

The vaccine effort currently underway is unprecedented in scope, with over 120 different vaccines being developed around the world, and over 10 already in clinical trials. At least two trials will likely be complete before the end of 2020.

“Let’s hope we’ll have the pleasant job of trying to decide which one is the best among multiple vaccines,” Greene says.

Support Our COVID-19 Research Efforts

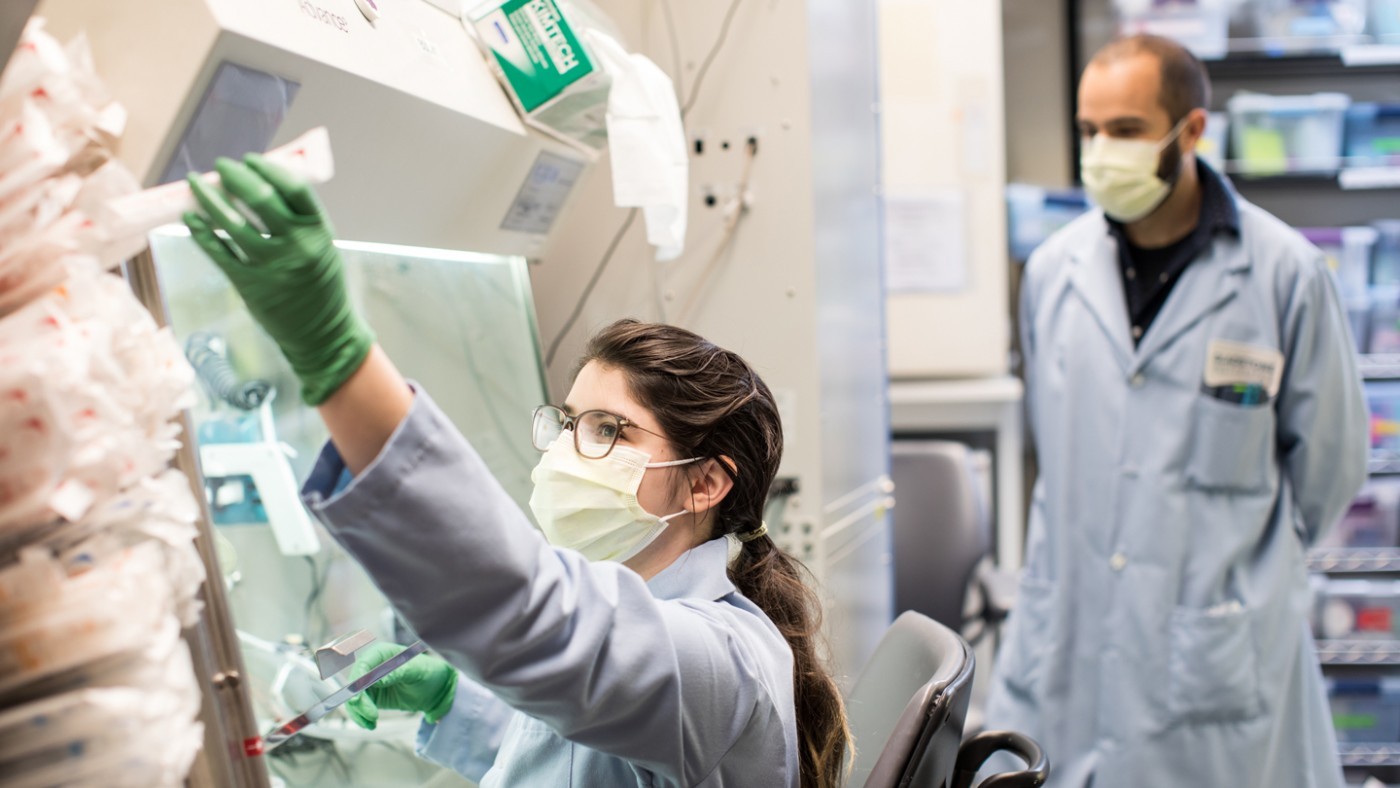

Gladstone scientists are moving quickly to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. Help us end this pandemic.

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

From fundamental insights to translational advances, here’s how Gladstone researchers moved science forward in 2025.

Gladstone Experts Alzheimer’s Disease Autoimmune Diseases COVID-19 Neurological Disease Genomic Immunology Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Infectious Disease Conklin LabScience in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Science in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

In this video, Gladstone scientists share how they used stem cells, gene editing, and AI to identify a gene driving heart defects in Down syndrome—and how reducing its levels in mice restored normal heart development, offering hope for future treatments

Gladstone Experts Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Pollard Lab Srivastava Lab AI Big Data CRISPR/Gene Editing Human Genetics Stem Cells/iPSCsScience in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

Science in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

In this video, Steve Finkbeiner and Jeremy Linsley showcase Gladstone’s groundbreaking “thinking microscope”—an AI-powered system that can design, conduct, and analyze experiments autonomously to uncover new insights into diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS.

Gladstone Experts ALS Alzheimer’s Disease Parkinson’s Disease Neurological Disease Finkbeiner Lab AI Big Data