Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

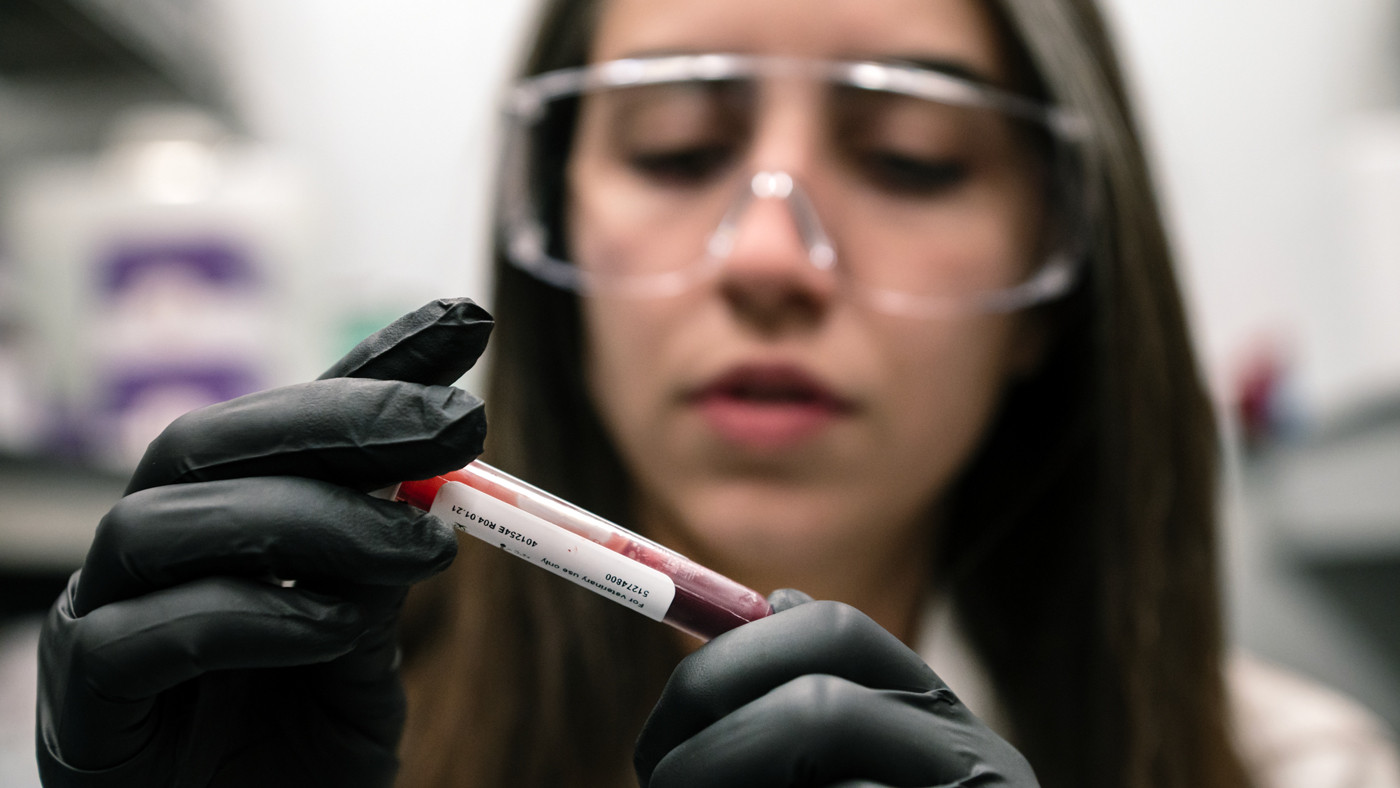

A team of scientists—including Yolanda Martí-Mateos, seen here—discovered that red blood cells act as hidden glucose sponges in low-oxygen conditions, explaining why people living at high altitude have lower diabetes rates and pointing toward new treatments.

Scientists have long known that people living at high altitudes, where oxygen levels are low, have lower rates of diabetes than people living closer to sea level. But the mechanism of this protection has remained a mystery.

Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes have explained the roots of the phenomenon, discovering that red blood cells act as glucose sponges in low-oxygen conditions like those found on the world’s highest mountaintops.

In a new study in the journal Cell Metabolism, the team showed how red blood cells can shift their metabolism to soak up sugar from the bloodstream. At high altitude, this adaptation fuels the cells’ ability to more efficiently deliver oxygen to tissues throughout the body, but it also has the beneficial side effect of lowering blood sugar levels.

The findings solve a longstanding puzzle in physiology, says Gladstone Investigator Isha Jain, PhD, the senior author of the study.

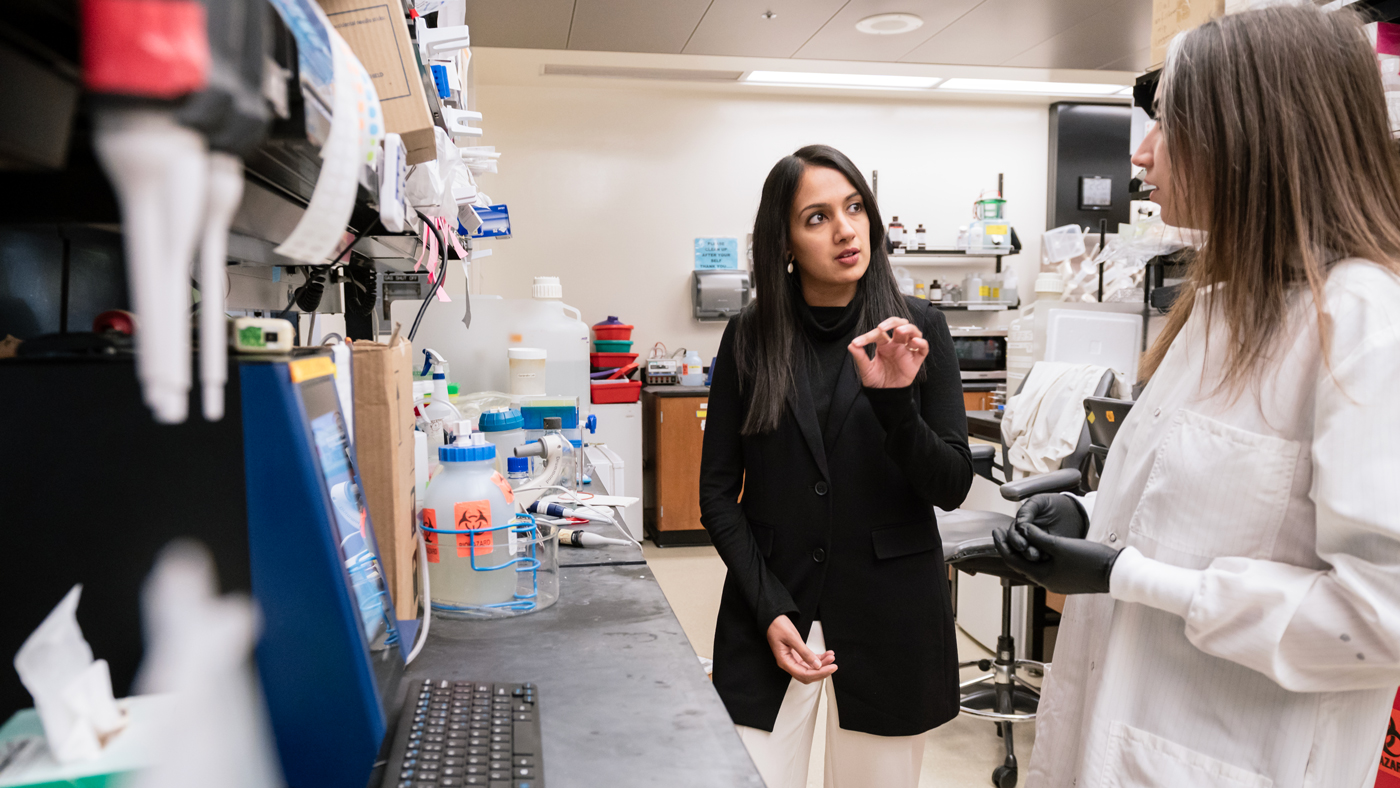

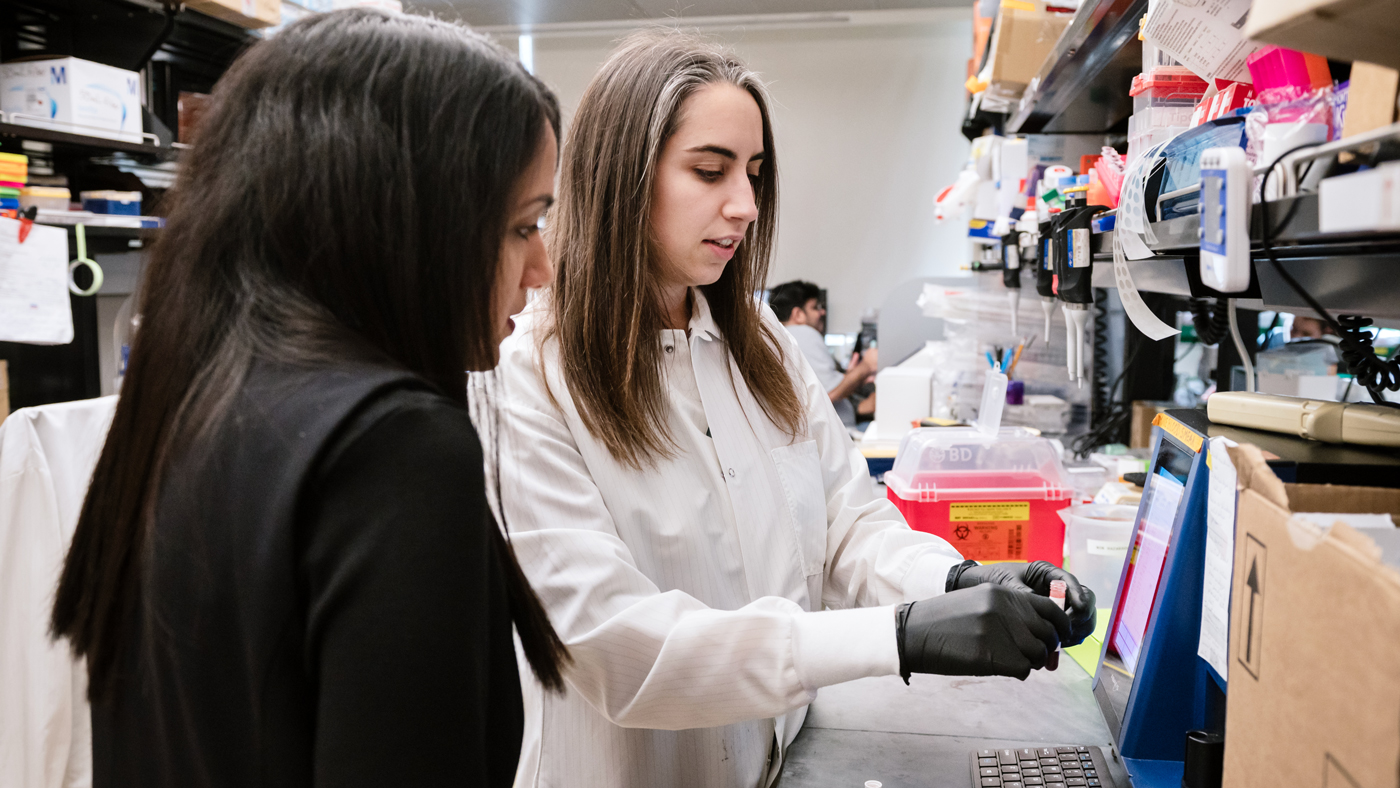

Isha Jain (left) and her colleagues, including Gladstone postdoc Yolanda Martí-Mateos (right), discovered that, at high altitude, red blood cells can shift their metabolism to soak up sugar from the bloodstream. Their findings open up entirely new ways to think about controlling blood sugar.

“Red blood cells represent a hidden compartment of glucose metabolism that has not been appreciated until now,” says Jain, who is also a core investigator at Arc Institute and a professor of biochemistry at UC San Francisco. “This discovery could open up entirely new ways to think about controlling blood sugar.”

The Hidden Glucose Sink

Jain has spent years probing how low blood-oxygen levels, called hypoxia, affect health and metabolism. During a previous study, her team noticed that mice breathing low-oxygen air had dramatically lower blood glucose levels than normal. That meant the animals were quickly using up glucose after they ate—a hallmark of lower diabetes risk. But when the researchers used imaging to track where the glucose was going, major organs couldn’t account for it.

“When we gave sugar to the mice in hypoxia, it disappeared from their bloodstream almost instantly,” says Yolanda Martí-Mateos, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Jain’s lab and first author of the new study. “We looked at muscle, brain, liver—all the usual suspects—but nothing in these organs could explain what was happening.”

Using another imaging technique, the team revealed that red blood cells were the missing “glucose sink”—a term used to describe anything that pulls in and uses a lot of glucose from the bloodstream. The cells, having long been considered metabolically simple, seemed like unlikely candidates.

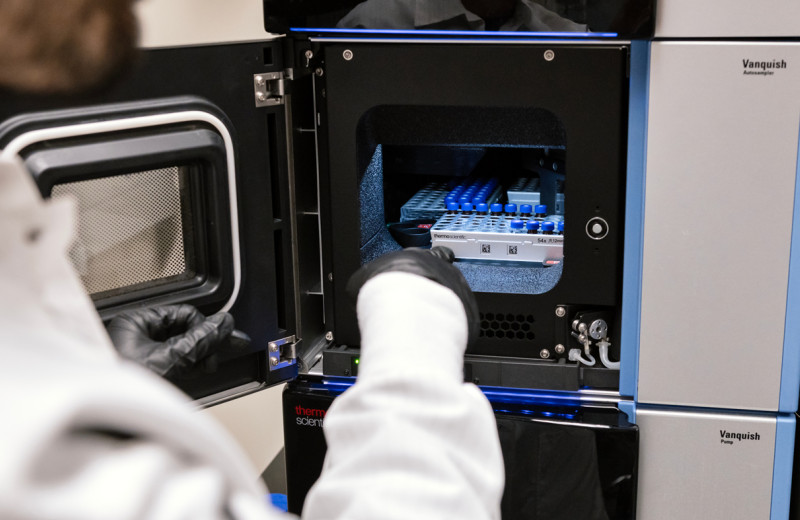

The researchers (including Martí-Mateos, seen here) found that in low-oxygen conditions, red blood cells take up more glucose than under normal oxygen, helping explain why people living at high altitude have lower rates of diabetes.

But further mouse experiments confirmed that red blood cells were indeed absorbing the glucose. In low-oxygen conditions, mice not only produced significantly more red blood cells, but each cell took up more glucose than red blood cells produced under normal oxygen.

To understand the molecular mechanisms of this observation, Jain’s team collaborated with Angelo D’Alessandro, PhD, of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and Allan Doctor, MD, from University of Maryland, who has long studied the function of red blood cells.

The researchers showed how, in low-oxygen conditions, glucose is used by red blood cells to produce a molecule that helps cells release oxygen to tissues—something that’s needed in excess when oxygen is scarce.

“What surprised me most was the magnitude of the effect,” D’Alessandro says. “Red blood cells are usually thought of as passive oxygen carriers. Yet, we found that they can account for a substantial fraction of whole-body glucose consumption, especially under hypoxia.”

A New Path to Diabetes Treatment

The scientists went on to show that the benefits of chronic hypoxia persisted for weeks to months after mice returned to normal oxygen levels.

They also tested HypoxyStat, a drug recently developed in Jain’s lab to mimic the effects of low-oxygen air. HypoxyStat is a pill that works by making hemoglobin in red blood cells grab onto oxygen more tightly, keeping it from reaching tissues. The drug completely reversed high blood sugar in mouse models of diabetes, working even better than existing medications.

“This is one of the first use of HypoxyStat beyond mitochondrial disease,” Jain says. “It opens the door to thinking about diabetes treatment in a fundamentally different way—by recruiting red blood cells as glucose sinks.”

Jain (left), Martí-Mateos (right), and the other scientists identified a drug that could reverse high blood sugar in diabetes, which worked better than existing medications when tested in mouse models.

The findings could extend beyond diabetes to exercise physiology or pathological hypoxia after traumatic injury, D’Alessandro notes, where trauma remains a leading cause of mortality in younger populations and shifts in red blood cell levels and metabolism may influence glucose availability and muscle performance.

“This is just the beginning,” Jain says. “There’s still so much to learn about how the whole body adapts to changes in oxygen, and how we could leverage these mechanisms to treat a range of conditions.”

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About the Study

The paper, “Red Blood Cells Serve as a Primary Glucose Sink to Improve Glucose Tolerance at Altitude,” was published by the journal Cell Metabolism on February 19, 2026. The authors are Yolanda Martí-Mateos, Ayush D. Midha, Will R. Flanigan, Tej Joshi, Helen Huynh, Brandon R. Desousa, Skyler Y. Blume, Alan H. Baik, and Isha Jain of Gladstone; Zohreh Safari, Stephen Rogers, and Allan Doctor of University of Maryland; and Shaun Bevers, Aaron V. Issaian, and Angelo D’Alessandro of University of Colorado Anschutz.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DP5 DP5OD026398, R01 HL161071, R01 HL173540, R01HL146442, R01HL149714, DP5OD026398), the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Dave and Renee Wentz, the Hillblom Foundation, and the W.M. Keck Foundation.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Featured Experts

Gladstone NOW: The Campaign

Join Us On The Journey

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

Developed by Gladstone scientists, HIV-seq could uncover new opportunities for treating HIV.

News Release Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabGladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab