Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

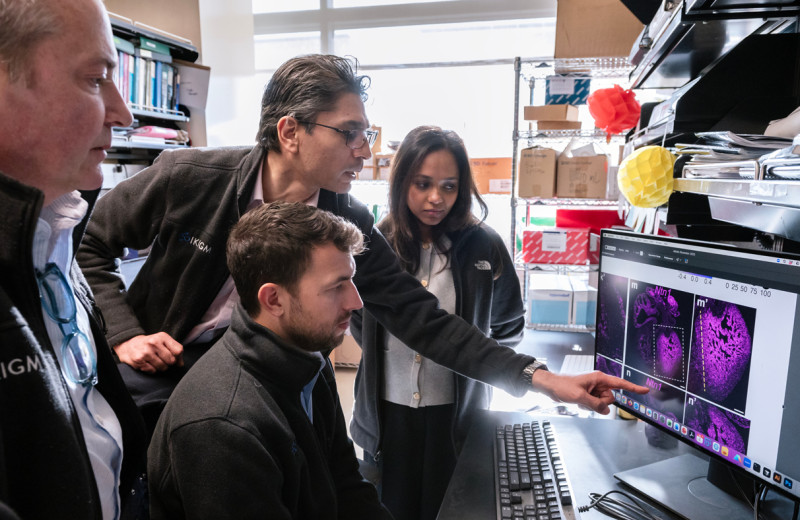

Gladstone's Melanie Ott, right, has been studying the process of HIV transcription for more than 30 years. Her lab, founded at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, ultimately seeks to cure individuals of HIV. Here, she collaborates with Julia Prigann, left, a postdoctoral scholar in the Ott Lab. Together with collaborators, they authored a commentary article in the journal Nature Microbiology.

In the decades since antiretroviral therapy became the standard of care for HIV, it has transformed quality of life for people living with the virus.

The life-saving therapy—a combination of many medicines—prevents development of AIDS, improves immune function, and markedly lowers the risk of transmitting the virus to others.

However, antiretroviral therapy is far from an HIV cure, says virologist Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, of Gladstone Institutes.

People who take the therapy still deal with chronic inflammation due to ongoing activation of the immune system, which can cause a host of other health problems—including higher rates of heart disease and certain cancers. And, if treatment is interrupted for even a short time, the virus bounces back.

The reason for this, Ott says, is that the drugs that make up today’s antiretroviral therapy don’t completely block all lingering HIV cells in the body from being active, nor do they eliminate these infected cells.

“Among the remaining infected cells, which together make up the HIV reservoir, some are still able to produce viral RNA and proteins,” says Ott, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology. “These problematic cells are responsible for rekindling infection and fueling chronic immune activation, even in the face of today’s best treatment regimen.”

In a commentary article now appearing in the journal Nature Microbiology, Ott and her collaborators make the case for prioritizing a new type of medicine that can be added to current antiretroviral therapy to silence the so-called “transcriptionally active” infected cells of the HIV reservoir.

Ott has been studying HIV transcription for more than 30 years. Her lab at Gladstone, founded at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, ultimately seeks to cure individuals of HIV.

Not Really Latent

Transcription is the critical first step of gene expression—the process by which DNA is able to transcribe into RNA to make proteins. Within the HIV reservoir, the transcription process produces new viral proteins, but without necessarily forming fully intact virus particles. This low-level viral activity is what’s believed to trigger the immune system, causing chronic inflammation.

So, while the HIV reservoir among those on therapy has traditionally been described as silent or latent, “evidence is accumulating that the viral reservoir might be leakier than initially thought,” Ott and her co-authors say in the article.

(“Leaky” refers to the fact that HIV isn’t fully contained in the reservoir as once thought.)

“Based on research across many institutions, we believe targeting transcription is a very important element missing from antiretroviral therapy,” says Julia Prigann, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Ott’s lab and first author of the commentary article. “Adding a drug that inhibits this process may potentially halt transcriptional activity, which would delay the virus from rebounding and reduce chronic inflammation.”

Over time, it may be possible to drive the virus into a state that scientists call deep latency, from which HIV is unlikely to reactivate.

Gladstone's Julia Prigann, left, and Melanie Ott, right, advocate for an additional type of medicine to be added to HIV antiretroviral therapy to address chronic inflammation and improve treatment outcomes for people living with the virus.

Considering All Possible Approaches

In the Nature Microbiology article, Ott and her team note that multiple drugs already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for non-HIV conditions have shown various levels of efficacy at blocking HIV transcription.

“More research is needed to understand the extent to which these drugs can block the ‘leakiness’ of HIV, and the mechanisms by which they do so,” says co-author Nadia Roan, PhD, a senior investigator at Gladstone. “But we are also pursuing complementary strategies, including ways to harness the immune system to eliminate these transcriptionally active HIV reservoir cells.”

Research programs targeting the HIV transcription process are ongoing at Gladstone and within the many laboratories of the HOPE Collaboratory, an NIH-supported Martin Delaney Collaboratory to “block-lock-stop” HIV transcription. Numerous HOPE researchers are co-authors of the commentary article.

“It’s time to close the loophole in current antiretroviral therapies—and targeting HIV transcription holds promise to do just that,” Ott says.

For Media

Kelly Quigley

Director, Science Communications and Media Relations

415.734.2690

Email

About the Study

The commentary article, “Silencing the transcriptionally active HIV reservoir to improve treatment outcomes,” appeared in the September 17, 2024, edition of Nature Microbiology. Authors include Julia Prigann, Rubens Tavora, Robert Furler O’Brien, Ursula Schulze-Gahmen, Daniela Boehm, Nadia Roan, Douglas Nixon, Lishomwa Ndhlovu, Susana Valente, and Melanie Ott.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau LabGene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Gene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Scientists at Gladstone show the new method could treat the majority of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Conklin Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingGenomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Genomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Findings of the new study in Nature could streamline scientific discovery and accelerate drug development.

News Release Research (Publication) Marson Lab Genomics Genomic Immunology