Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

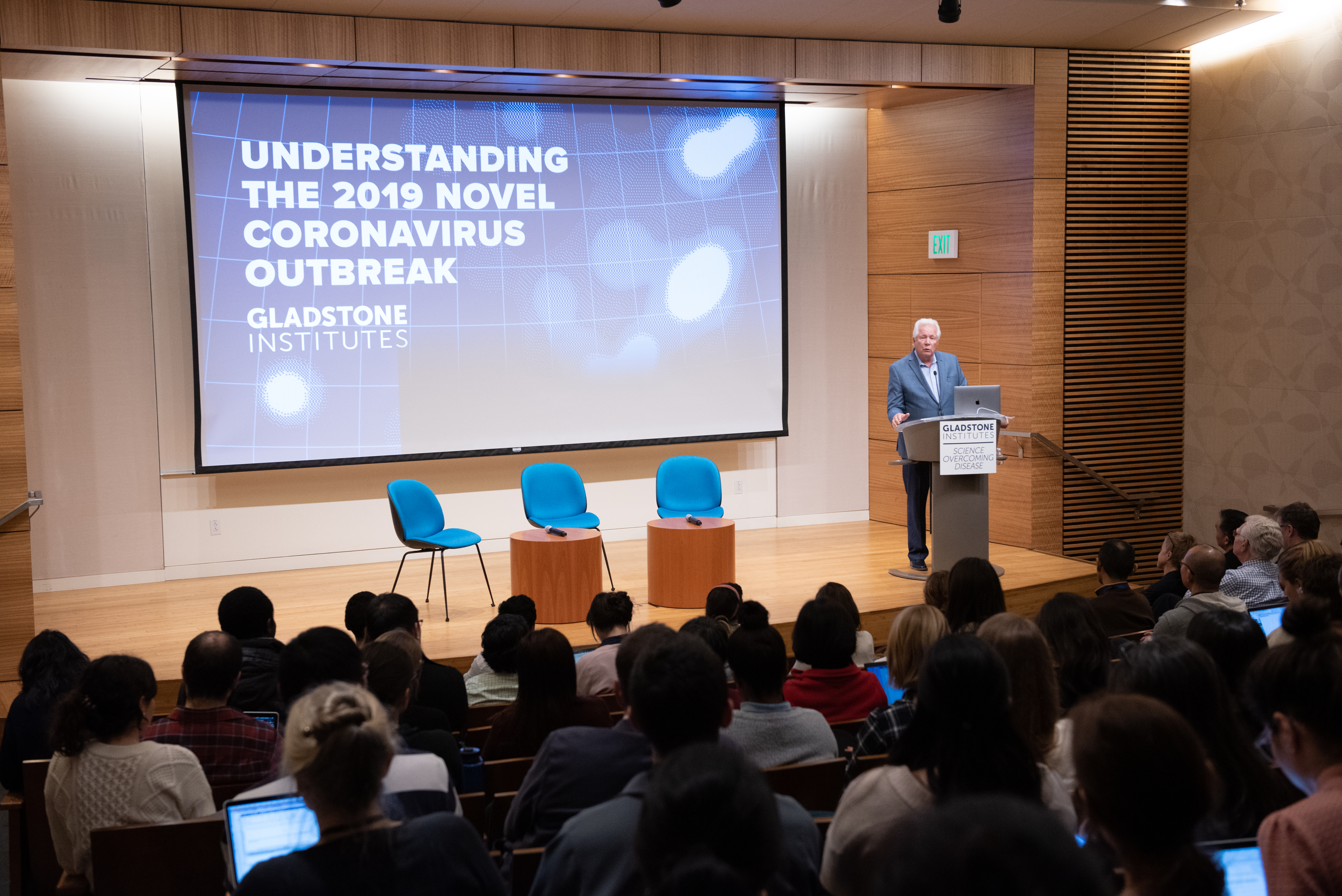

Gladstone hosted a public briefing on the coronavirus outbreak featuring (left to right) Melanie Ott, Charles Chiu, and Warner Greene.

The deadly new coronavirus that emerged in the Hubei province of China in December, 2019 has infected upwards of 45,000 people. As of February 11, 2020, the virus, now named COVID-19, has claimed slightly more that 1,100 lives in mainland China, and 27 countries are now reporting COVID-19 infections. On January 30, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global health emergency.

To stem the spread of the virus, China has imposed quarantines on an unprecedented scale.

But what is this new virus, how does it spread, how can we protect ourselves against infection, and what are the prospects for rapid and effective treatment?

Virologists at Gladstone have been following the outbreak of COVID-19. They are using their experience of other virus-borne illnesses and epidemics to answer some common questions about the coronavirus outbreak.

Warner C. Greene, MD, PhD, is the director of the Center for HIV Cure Research at Gladstone as well as a professor of medicine, microbiology and immunology at UC San Francisco. Greene’s research spans virology and immunology, with a focus on HIV and related viruses, and on HIV-AIDS pathology.

Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, is a senior investigator at Gladstone and professor of medicine at UC San Francisco. Her lab focuses on understanding the interactions between pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis viruses and the cells they infect.

How does the coronavirus spread?

Greene: Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that predominantly circulate in bats. They occasionally transfer from bats to other animals, and then to people. The virus responsible for the current outbreak, now called COVID-19, is thought to primarily spread from person to person through respiratory droplets, which are created when a person coughs or sneezes.

What should I do if I've been in contact with someone who shows symptoms?

Greene: First of all, let’s keep in mind that in the United States, a person showing respiratory symptoms most likely has a common cold. So far, there have only been 12 confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection in the United States. Flu infections are far more common and a far greater threat. Around 30,000–40,000 people die of the flu every year in the United States. Yet, we tend to be less concerned with the flu since we have a vaccine (it’s not too late to get your flu vaccine this season) and medications that can partially treat the infection.

Regardless, as for any upper respiratory illness, the best protection includes avoiding sick people’s coughs and sneezes, disinfecting potentially contaminated surfaces (door knobs, keyboards, etc.), and washing your hands frequently. If you suspect that you are ill, restrict activities outside your home to avoid spreading infection, cover your coughs and sneezes, and contact your doctor’s office prior to visiting.

Will the travel restrictions currently in place contain the outbreak?

Greene: Tremendous efforts are being taken to try to prevent major spread of this virus within and outside of China. Currently, no one can accurately predict this virus’s ultimate reach.

The spread of the deadly SARS virus, a close cousin of COVID-19 that killed some 700 people in 2002–2003, was actually stopped by public health containment measures (isolating the sick, trace contacts, and quarantine), not through drug treatment.

Will a face mask protect me from infection?

Greene: It’s important for medical professionals who work with infected patients to wear properly-fitted respirator masks (e.g. N95 respirators). Masks are also recommended for family members or other people in frequent contact with an infected person, and of course for the infected persons themselves.

However, the surgical masks you can buy at the drugstore do not provide effective protection from infection. A surgical mask is primarily used to protect patients and healthcare workers from people who may have a respiratory infection or to protect sterilized or disinfected medical devices and supplies like those in an operating room.

How did the virus spread from animals to humans?

Ott: We’re not sure yet. In general, it is thought that the virus passes from bats to an intermediate host, and then from that host to humans. The intermediate host for COVID-19 has not been definitively identified yet.

What are the symptoms of infection, and when should people seek medical advice?

Ott: The most common symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Most people will recover on their own by keeping their fever under control, using a room humidifier, staying well hydrated, and basically staying home to rest. If symptoms become worse or concerning, call your healthcare provider.

How quickly could researchers generate a vaccine?

Ott: The genetic sequence of COVID-19 is known, and scientists are already working on developing a vaccine. Vaccine development has sped up in recent years, and it’s possible that an effective vaccine could be generated in a matter of months. However, that vaccine would then have to go through clinical trials to ensure its safety, and then it would take several more months to manufacture enough doses of the vaccine to reach the most vulnerable populations. The entire process is likely to take more than a year.

What treatments are currently available for people who are infected?

Ott: We don’t have targeted treatments yet, but people who are infected may receive antiviral medications including Tamiflu® and drugs originally developed to fight HIV and Ebola.

Greene and Ott both recently spoke at a special public briefing on the coronavirus outbreak. Watch a live recording of the event.

Support Discovery Science

Your gift to Gladstone will allow our researchers to pursue high-quality science, focus on disease, and train the next generation of scientific thought leaders.

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

From fundamental insights to translational advances, here’s how Gladstone researchers moved science forward in 2025.

Gladstone Experts Alzheimer’s Disease Autoimmune Diseases COVID-19 Neurological Disease Genomic Immunology Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Infectious Disease Conklin LabScience in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Science in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

In this video, Gladstone scientists share how they used stem cells, gene editing, and AI to identify a gene driving heart defects in Down syndrome—and how reducing its levels in mice restored normal heart development, offering hope for future treatments

Gladstone Experts Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Pollard Lab Srivastava Lab AI Big Data CRISPR/Gene Editing Human Genetics Stem Cells/iPSCsScience in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

Science in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

In this video, Steve Finkbeiner and Jeremy Linsley showcase Gladstone’s groundbreaking “thinking microscope”—an AI-powered system that can design, conduct, and analyze experiments autonomously to uncover new insights into diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS.

Gladstone Experts ALS Alzheimer’s Disease Parkinson’s Disease Neurological Disease Finkbeiner Lab AI Big Data