Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Virologist Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, shares scientific insights into the virus that prompted California Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency in December.

Bird flu is increasingly making state and national headlines: The first U.S. person with a severe case of the virus died in early January, according to the Louisiana Department of Health. And just days later, the San Francisco Department of Public Health announced its first case—a child with the telltale signs of fever and pinkeye who tested positive for the H5N1, the type of influenza A that causes bird flu. The child has since recovered.

Both of these developments came shortly after California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency in late 2024 to strengthen California’s response to bird flu. The virus has spread in at least 16 states among dairy cattle following its first confirmed detection in Texas and Kansas in March 2024.

But what is the real threat to the average person? And what precautions, if any, should people be taking today as bird flu expands beyond its typical winged victims? Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology, shares insights into the developing situation.

It’s clearly unusual that people are now contracting bird flu. How is the virus normally spread, and how has it jumped to humans?

As its name suggests, avian influenza is quite common in birds and has been for some time. Initially called “fowl plague,” it has caused several outbreaks in the 19th and 20th centuries—it was only in the 1950s that scientists linked it to flu viruses.

In regards to the H5N1 subtype that’s circulating today, the CDC reports well over 100 million poultry affected and nearly 11,000 cases in wild birds. In nearly all of the probable human cases, of which there have been less than 100 so far, people have had direct exposure to infected animals in poultry farms or backyards—this contact is likely when the virus got into their eyes, nose, or mouth.

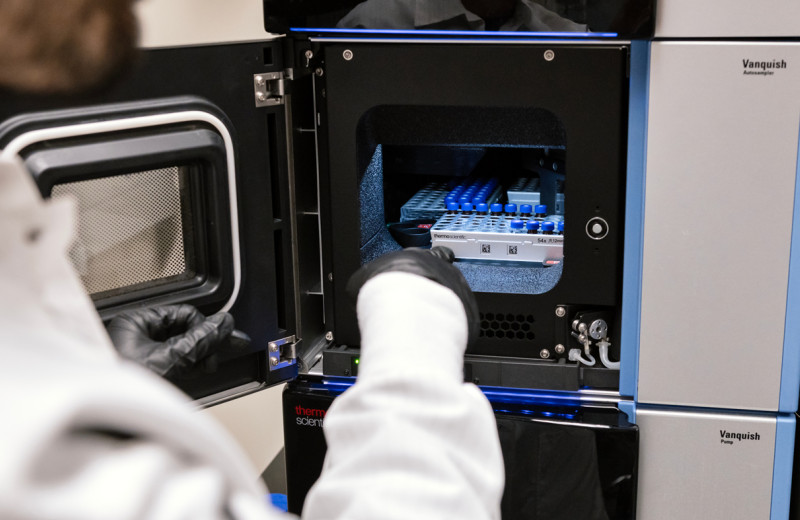

At this time, it’s still extremely rare for this virus to spread from person to person. At Gladstone, we’re watching the situation very closely, and we have the tools to be able to analyze the virus rapidly if needed.

The bird flu virus was first detected in dairy cattle in March 2024; as of mid-January 2025, outbreaks in cows have been reported in 16 states.

Are you concerned the virus could become an urgent public health issue in the near future?

This is already an urgent issue, as our food chain is reliant on the animals contracting and spreading the virus. Evidence has shown that the infection often spreads among cows, especially through milking machines, where the virus can persist after contact with contaminated milk.

However, unlike birds, cows show few symptoms. And while testing for bird flu is mandatory for raw milk, it’s only required for dairy cattle in special instances, such as when the animals are moved across state lines. So, we don’t really know how widespread the infection is among cows. We need to consider that dairy cattle may represent a huge incubation for the virus, allowing it to mutate in ways that could become more dangerous for people. Then we would have a huge problem.

What would have to happen for the virus to become more infectious in humans?

Influenza viruses, in general, are known to mutate quickly. That’s why we need seasonal flu vaccines; the virus is always changing, and some mutations can be more dangerous than others.

Bird flu is no different. In fact, a study published in December revealed that just a single mutation to the H5N1 virus circulating in cows could enhance its ability to attach to human cells, potentially increasing the risk of it passing efficiently from person to person. And other types of mutations could be just as problematic. For example, a change in the virus’s polymerase genes, which play a key role in viral replication, could increase viral production and make the disease more severe.

We’re playing with fire by letting the virus go largely uncontrolled in agricultural settings, because it’s possible new mutations will occur that will make this a very dangerous disease for humans.

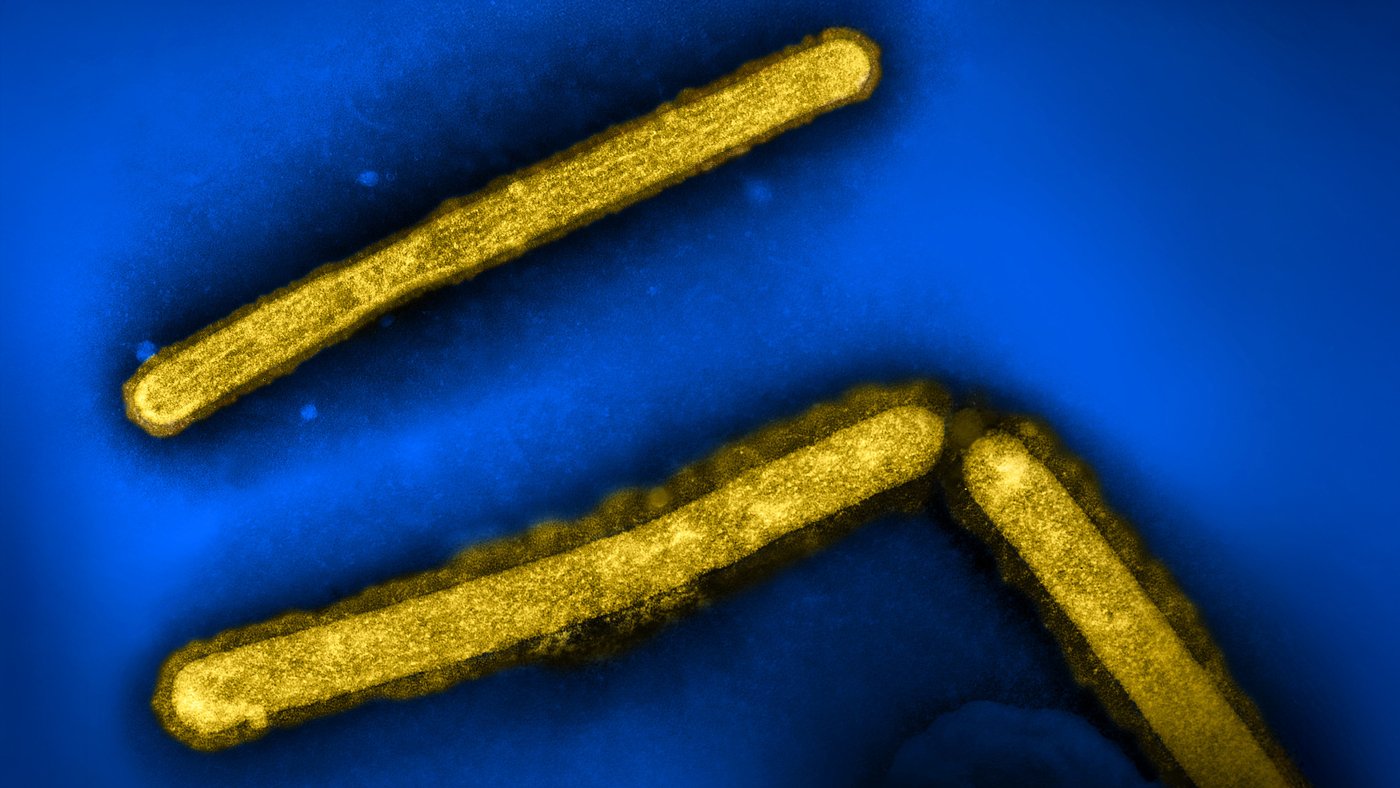

H5N1 bird flu particles, captured by the Centers for Disease Control using a transmission electron microscope. (Photo courtesy of CDC and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.)

For the average person, what types of precautions make sense today?

While there’s no immediate human threat, we should all be aware of common-sense safeguards.

First, remember that birds can travel far from where they were infected, and they may end up in your backyard or your favorite dog beach. The virus has already been detected in sea mammals in the U.S. and throughout the world. So, if you encounter a dead bird on the beach or at the park, be even more vigilant about not allowing your dog to make contact with it. Health officials also warn against consuming raw milk, which could contain the virus and lead to infection.

Finally, get your flu shot if you haven’t already. While current flu vaccines were not developed to protect against bird flu, they will protect against becoming coinfected with seasonal flu and bird flu. This is important, as coinfections may promote a genetic exchange between the two viruses that could possibly generate a more dangerous, human-adapted pathogen. Fortunately, the U.S. government has already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines for a worst-case scenario, so we wouldn’t be starting from zero if signs of a pandemic emerged. Stay informed and know the situation could change quickly.

"We’re playing with fire by letting the virus go largely uncontrolled in agricultural settings."

At Gladstone, what type of research are you doing today that could potentially help limit the impact of the bird flu?

Gladstone is equipped with high-security biocontainment laboratories and the expertise to study this virus. We’re currently developing biosafety protocols to safely import the virus into our facilities. We’re also working on rapid flu diagnostics, including for H5N1. And, we’re home to leading-edge vaccine technology, with new approaches being developed in the lab of Magnus Hoffmann, PhD, who's also working on a universal flu vaccine. Ever since Gladstone created its virology institute in 1991, we’ve had a history of responding rapidly to viral outbreaks with discoveries that can be applied to patient health.

For Media

Kelly Quigley

Director, Science Communications and Media Relations

415.734.2690

Email

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

Developed by Gladstone scientists, HIV-seq could uncover new opportunities for treating HIV.

News Release Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabGladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab