Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

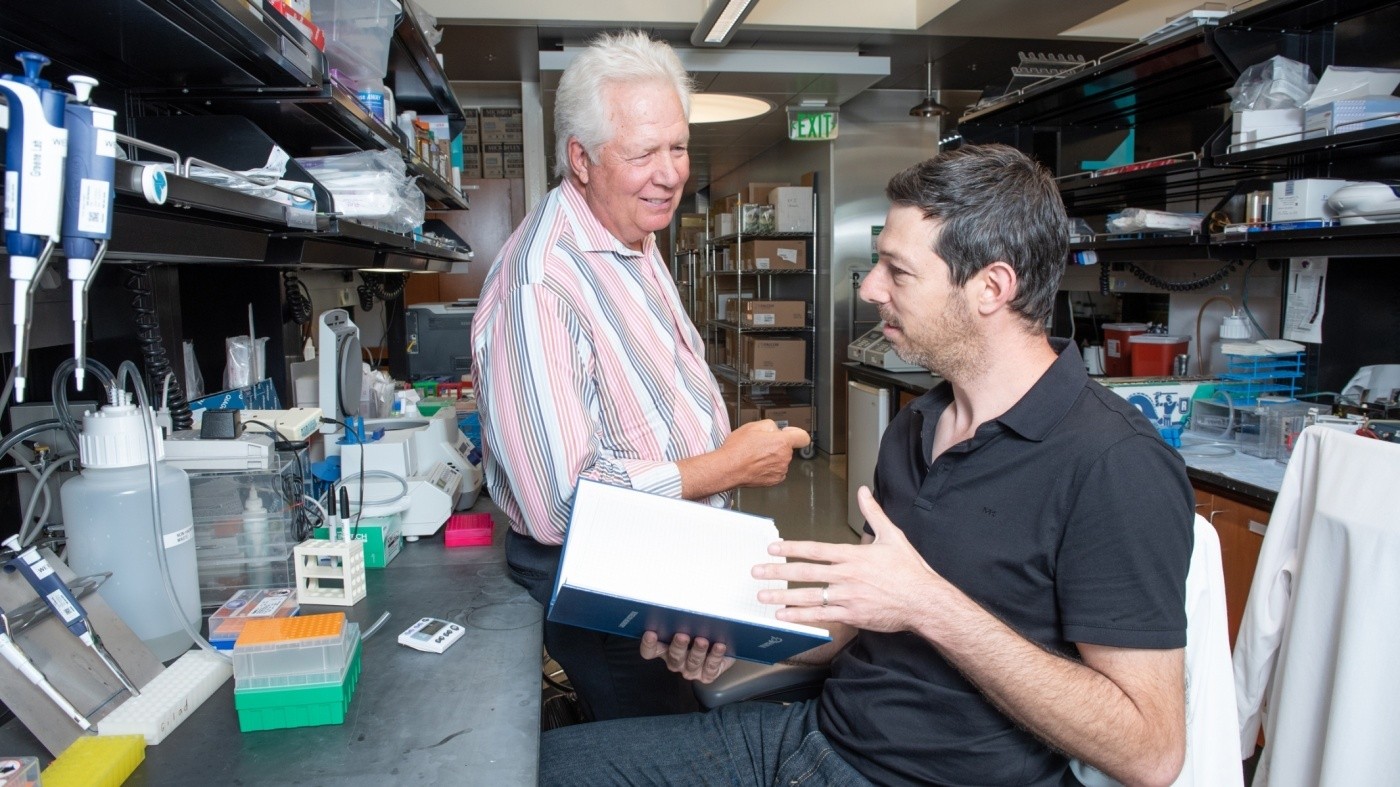

Gladstone researchers Warner Greene (left) and Eytan Herzig (right) collaborated with Xyphos Biosciences, Inc., to develop a novel immunotherapy for HIV.

A team of Gladstone scientists and their partners at Xyphos Biosciences, Inc. describe a new way of attacking cells infected by HIV in the October 31, 2019 issue of the journal Cell. The work showcases a novel version of CAR-T, the technology known for its recent successes in fighting blood cancers. With improvements lending it greater breadth of coverage and versatility, the new technology, called convertibleCAR, shows great promise in several therapeutic areas, particularly in the fight against HIV, as it could be used to shrink the reservoir of infected cells that persists in patients under antiretroviral therapy.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses HIV infection but does not eradicate the virus from its hosts. Some virus goes into hiding inside cells, forming what is termed the latent HIV reservoir. From this hideout, the virus is poised to restart a deadly infection as soon as the patient interrupts treatment, forcing patients to adhere to a life-long regimen of daily ART pills.

The latent reservoir is the main barrier to a cure for HIV/AIDS, and targeting it has been a long-standing goal for Warner C. Greene, MD, PhD, director of the Center for HIV Cure Research at Gladstone Institutes and senior author on the new study. The bigger the reservoir, the harder it is to control, and the faster the virus rebounds upon lapse in treatment.

“Our efforts are focused on shrinking the latent reservoir and engineering an immune response that can control the smaller reservoir, allowing discontinuation of anti-retroviral therapy. This ‘reduce-and-control strategy’ could lead to a sustained HIV remission or a functional cure,” said Greene, who is also the Nick and Sue Hellmann distinguished professor of translational medicine, and a professor of medicine, microbiology, and immunology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Conventional CAR-T technology involves engineering a form of immune cells, known as cytotoxic T cells, to express on their surface a stripped-down version of an antibody. This antibody portion allows the cytotoxic T cell to home in on its target cell––for example, a leukemic cell––and to attack and destroy it. But for each new pathogen or cancer cell, a new conventional CAR-T cell must be manufactured, with a new targeting antibody on its surface. That’s time-consuming and costly.

By contrast, the convertibleCAR technology makes it possible to combine the cytotoxic “killer” T cell with any number of antibodies. This feature is crucial for fighting a pathogen such as HIV, of which hundreds of different variants are known to exist.

“This flexible technology has the potential to revolutionize the CAR-T system by allowing a one-time delivery of convertibleCAR cells to the patient and giving the physician the ability to administer the antibody or cocktail of antibodies best suited to treat the patient’s disease, be it HIV/AIDS or a leukemia,” said Greene.

Such applications are promising, but are early in development.

“This study is a proof-of-concept experiment, where we show that it is possible to combine a promising kind of antibody against HIV, known as ‘broadly neutralizing antibodies’, with convertibleCAR cells to successfully attack the reservoir,” said Greene.

James Knighton, CEO and co-founder of Xyphos, where the convertibleCAR was invented, concurs. “The results generated through this project provide a remarkable validation for the technology and offer the potential to change the way disease is treated today.”

A Modular Weapon for a Shape-Shifting Foe

Conventional CAR-T cells have proven remarkably successful at inducing remission of blood cancers, such as lymphomas and childhood leukemia.

But as therapy against HIV infection, conventional CAR-T cells are not perfect.

“Some shortcomings of conventional CAR-T,” as Eytan Herzig, a scientist in Greene’s lab and the study’s first author, explained “are that they are engineered to target a single molecule on cancer cells, and that they cannot be controlled once injected into a patient’s body.”

HIV is a rapid shape-shifter known to evade every form of single-drug therapy. An infected person harbors a vast number of different forms. There would be no long-term success with a CAR-T cell carrying a single antibody as a weapon against HIV.

Xyphos scientists overcame many of these shortcomings by separating the targeting antibody from the cytotoxic killer cell.

“We engineered the convertibleCAR cell so the T cell would express on its surface a human receptor protein called NKG2D that had been minimally modified,” explained David W. Martin, MD, chief scientific officer of Xyphos. That modified NKG2D receptor can turn the T cell into a potent killer, but only when bound to its partner. Its partner is a protein called MIC-A, which Xyphos scientists trimmed down and modified so it would bind exclusively to the modified NKG2D receptor on the convertibleCAR cell. Xyphos scientists then fused it to the base of the targeting antibody, creating what they call a MicAbody®. As a result, the targeting MicAbody binds tightly and exclusively to the convertibleCAR cell.

“A MicAbody is an elegant solution, and much easier to create and produce en masse than a whole new CAR-T cell,” Martin continued. Instead of needing a different CAR cell for each target, scientists can administer a single convertibleCAR cell and combine it with the MicAbodies of their choosing.

In addition, the modified NKG2D-Mic combination provides a convenient means of delivering a kill switch if rogue CAR-T cells need to be eliminated, or a boost if the cells need to be activated after a long rest.

“Because it is modular, we believe convertibleCAR will be safer, more versatile, and amenable to external control than conventional CAR-T,” said Martin.

But would the technology work on something beyond blood cancers for which it was originally developed?

A Powerful Combination

In their ongoing efforts to tackle the latent HIV reservoir, Herzig and Greene had been testing anti-HIV antibodies called “broadly neutralizing antibodies” or bNAbs, in lab parlance.

“They are called broadly neutralizing antibodies because they don’t just neutralize one specific strain of virus; they neutralize a vast number of strains,” explained Herzig.

But bNAbs alone are not enough to kill HIV-infected cells. They need killer T cells, and the problem in HIV-infected patients is that their killer T cells are exhausted, or that the latent reservoir contains viruses that are resistant to these cells.

Herzig and Greene reasoned that by combining bNAbs and convertibleCAR cells, they might get the killing power they needed.

They collaborated with Xyphos scientists to create MicAbodies from bNAbs, and went about testing convertibleCAR cells combined with Mic-bNAbs in various lab assays.

Herzig tested these combinations on various types of CD4 T cells—the natural targets of HIV—infected in the lab with various HIV strains. In particular, he used a cell preparation derived from human tonsils; tonsil T cells are known to be a latent reservoir. He wanted to make sure that the convertibleCAR/Mic-bNAb combination would kill the T cell–types representative of the actual latent reservoir.

The results were remarkable: convertibleCAR cells combined with Mic-bNAbs specifically killed infected CD4 T cells, but not uninfected cells. They only killed infected cells when combined with Mic-bNAbs, and not when added alone or combined with MicAbodies not directed at HIV. They killed CD4 T cells infected in the lab with a variety of virus strains. And when combined with a Mic-bNAb and a MicAbody directed at cancer cells, convertibleCAR cells could efficiently kill both the cancer cells and the HIV-infected cells mixed in the same culture.

In other words, convertibleCAR was demonstrating exactly the versatility and specificity it had been designed to achieve.

Finally, Herzig and Greene tested whether the convertibleCAR/Mic-bNAb platform could attack the latent reservoir present in the blood of HIV-infected individuals on ART. To make these cells visible to the convertibleCAR cells, the cultures had to first be activated with compounds known as strong “latency-reversing agents”.

Within 48 hours of exposure, more than half of the activated, HIV-expressing cells had been wiped out.

“This platform has great promise,” concluded Greene.

The Outlook

But many obstacles remain before this technology can enter the clinic.

For one thing, since the latent reservoir is normally invisible to the immune system, it must first be activated to produce viral proteins that the bNAbs can see and target. The current cornucopia of compounds that can awaken reservoir cells, the latency reversing agents, includes chemicals that are effective but too toxic to be used in patients, or compounds that are safe but not very potent.

“But if we can activate 5 to 10 percent of the reservoir at a time and kill it with convertibleCAR armed with MicAbodies repeatedly and regularly, we could with time significantly reduce the reservoir,” said Herzig.

“Still, better reactivating agents are needed,” said Greene.

In addition, convertibleCAR cells produced in the lab might trigger unwanted immune responses in the host, unless they are derived from the patient’s own cells. That’s an expensive proposition. Xyphos is currently exploring universal donor cells, cells that are genetically modified to avoid attacking or being rejected by the patient’s cells, which could lead to a single convertibleCAR cell for all patients, all targets, and multiple diseases.

With these advances, the promise of convertibleCAR combined with bNAbs is undeniable.

“ConvertibleCAR technology could help propel progress to an HIV cure, especially now that great progress is being made in creating universal donor cells. These cells will eventually reduce the current high cost of this approach,” said Greene.

Moreover, “the possibility of multiplexing a single convertibleCAR cell with several MicAbodies makes this platform quite promising for tackling other conditions associated with multiple cell or pathogen variants—cancer in particular—and for avoiding the universal problem of drug resistance,” said Knighton.

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau LabGene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Gene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Scientists at Gladstone show the new method could treat the majority of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Conklin Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingGenomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Genomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Findings of the new study in Nature could streamline scientific discovery and accelerate drug development.

News Release Research (Publication) Marson Lab Genomics Genomic Immunology