Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

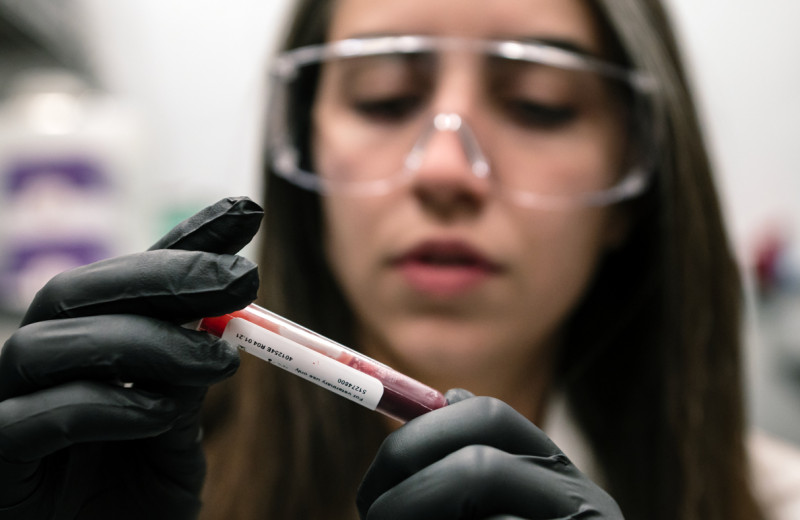

Scientists in the lab of Katerina Akassoglou, PhD, discovered that decreasing levels of p75 neurotrophin receptor prevented obesity and metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow, Gladstone Institutes]

Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have discovered an unusual regulator of body weight and the metabolic syndrome: a molecular mechanism more commonly associated with brain cells. Lowering levels of P75 neurotrophin receptor (NTR)—a receptor involved in neuron growth and survival—protected mice fed a high-fat diet from developing obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver disease.

In addition to its role in the brain, p75 NTR is present throughout the body, including in the liver and fat cells. Previous research implicated p75 NTR in liver disease and insulin resistance, two consequences of metabolic syndrome and obesity. In the current study, published in Cell Reports, the researchers investigated the relationship between p75 NTR and a diet high in fat—often the cause of these problems. The scientists discovered that the receptor helped regulate metabolic processes that control body weight, and reducing the number of p75 NTR in fat cells prevented weight gain in mice.

“We’ve identified a novel molecular mechanism that regulates energy expenditure and may help prevent obesity and the metabolic syndrome,” says lead author Bernat Baez-Raja, PhD, a research scientist in the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. “The complete protection from obesity and metabolic dysfunction in the study animals, without any differences in appetite or physical activity, suggests that p75 NTR is a key regulator of fat burning.”

The researchers experimentally removed p75 NTR from mice and then fed them a high-fat diet. Remarkably, these mice were resistant to weight gain and remained healthy and lean after several weeks on the diet. Conversely, normal, “wildtype” mice fed the same diet became obese, had larger fat cells, higher insulin levels, and developed signs of fatty liver disease.

Notably, there was no difference between the wildtype and p75 NTR-depleted mice regarding diet, overall energy consumption, or physical activity. Rather, the experimental mice had significantly greater energy expenditure than the wildtype mice, mostly likely because they burned more fat.

“The robustness of the effect is quite remarkable,” says senior author Katerina Akassoglou, PhD, a senior investigator at Gladstone. “Since neurotrophins and their receptors control the communication between the brain and peripheral organs, they could be new therapeutic targets with implications in both metabolic and neurologic diseases.” Dr. Akassoglou is also a professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

In a final set of experiments, the investigators showed that p75 NTR’s role in fat cells in particular contributed significantly to regulating body weight. Deleting p75 NTR only from fat cells resulted in similar outcomes as deleting the receptors from all cell types in the body. What’s more, transplanting fat cells from the experimental mice into wildtype mice also protected the wildtype mice from developing obesity.

The researchers say the next step is to develop small molecules or drugs that regulate p75 NTR to reproduce this effect and potentially serve as a therapeutic intervention for obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Other Gladstone scientists on the study were Eirini Vagena, Dimitrios Davalos, Natacha Le Moan, Jae Kyu Ryu, and Justin Chan. Researchers from the University of California, San Diego, the University of Glasgow, and King’s College London also took part in the research. Funding was provided by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the UCSF Liver Center, the UCSF Diabetes and Endocrinology Center, the Spanish Research Foundation, and the Medical Research Council.

Featured Experts

Support Our COVID-19 Research Efforts

Gladstone scientists are moving quickly to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. Help us end this pandemic.

Red Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

Red Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

New study shows red blood cells act as hidden glucose sponges in low-oxygen conditions, explaining why people living at high altitude have lower diabetes rates and pointing toward new treatments.

News Release Research (Publication) Diabetes Jain LabRoddenberry Gift Ushers Gladstone Stem Cell Research into the Future

Roddenberry Gift Ushers Gladstone Stem Cell Research into the Future

The path to medical breakthroughs lies in bold, ambitious science

Donor Stories Institutional News Spinal Cord Injuries Alzheimer’s Disease Diabetes Roddenberry Stem Cell Center Bruneau Lab Ding Lab Huang Lab McDevitt LabScientists Discover Drug that Increases “Good” Fat Mass and Function

Scientists Discover Drug that Increases “Good” Fat Mass and Function

Anti-cancer drug prevented less weight gain and caused mice to burn more calories thanks to higher levels of metabolism-boosting brown fat.

Ding Lab Metabolism Diabetes