Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

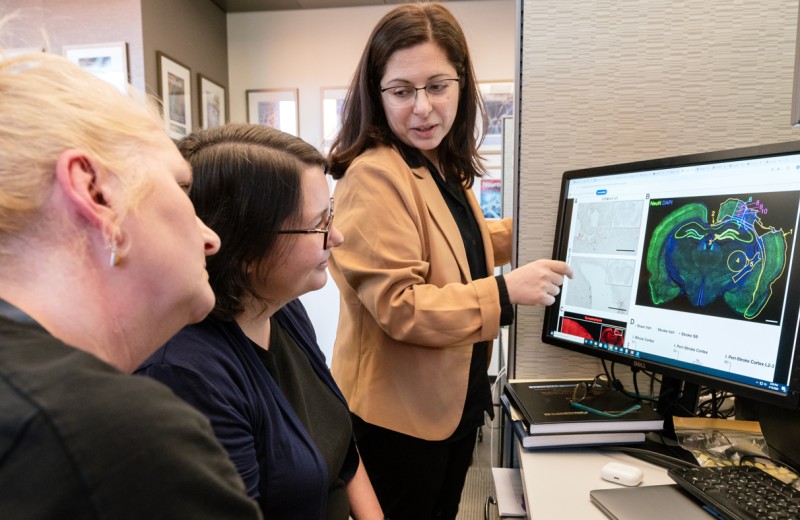

Jeanne Paz, PhD, studies epilepsy with optogenetics, a tool that scientists use to turn certain cells in the brain on or off with light. Paz received a PhD from the Université Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford University.

What brought you to Gladstone?

Gladstone does outstanding science and is dedicated to training and mentoring. And the people who work at Gladstone have a positive attitude and are extremely focused on how to resolve fundamental questions related to disease. Gladstone also supported my work on a specific disease. Many other institutions where I interviewed were looking for just “the best scientist,” and it didn’t really matter to them what exactly the scientist was going to do. I also really liked that while Gladstone consists of three different institutes, the scientists are united in disease-oriented research to reduce suffering in the world.

Were you interested in science as a child?

Coming from a family of twenty physicists, I spent a big part of my childhood in my parents’ lab at the astronomy observatory where they were working. My father was a theoretical physicist, and my mother was an experimental physicist. Their fascination for science and understanding the world was infectious. I was expected to become a physicist like all my family members. However, instead of being fascinated by physics, I was more fascinated by how my parents’ brains worked to understand such complicated matters as the universe.

What or who influenced your decision to work in science?

During my childhood, I was exposed to the violence of war, which convinced me to take a biomedical path. With this motivation, I enrolled in medical school at age 17. During my training, I was struck by the lack of treatments for epileptic seizures that resemble “terrorist attacks” in the brain.

One in 26 people develops epilepsy during the course of their life, and despite many decades of research, we still don’t understand what causes seizures, and we still do not have a cure. This “black box” convinced me to change my career plan to a scientific path aimed at understanding the brain. With this goal in mind, I earned a PhD in neuroscience at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris. There, I developed a passion for understanding how cells communicate in the brain and how disrupting them causes neurological disorders, such as epilepsy.

What do you do when you are not working in the lab?

I spend time with my family. Lately, I have been reading Diary of a Wimpy Kid to my daughter (her new favorite book) and trying to fit a few other things that I enjoy into my life, like driving off-road in my Jeep Wrangler, reading old books from previous centuries, hiking, and dancing.

What has been your greatest challenge as a scientist?

Despite all the knowledge that we have, I need to keep my mind open so that I can always think outside of the box, which I believe is the most critical feature of a scientist.

What advice would you give a postdoctoral fellow?

Follow the science that you are most passionate about, and reach out to find other excited scientists to collaborate with. Science is much more fun if you can share it with other people who care about it as much as you do. Always keep your mind open. It can push your science towards new, unanticipated horizons.

When I was a postdoctoral fellow, I was very lucky to have found such passionate people. When I mentored Zoya Farzampour, a student at Stanford, we would get goose bumps each time we had a beautiful recording of a neuron on the oscilloscope. I remember the first time I could turn off an intractable seizure with light; we both cried from excitement in front of the oscilloscope.

Later on, I worked with Tom Davidson (postdoctoral fellow) and Eric Frechette (clinical fellow in epileptology) to develop a new approach to disrupt seizures in real time. This project was born from a combination of several different brains that each brought a different piece of the puzzle to solve a complicated problem.

If you could learn to do anything, what would it be?

I would like to visit space and other planets. I learned from my own experience that traveling opens your mind and widens your perceptions. I always wondered what would be the effect of traveling beyond Earth.

Name one thing that not many people know about you.

I love alpinism. I find the contact with nature essential to my life. Mountains remind me of my childhood spent at the observatory with my parents.

If you could meet any scientist from any point in time, who would it be and why?

Marie Curie. She was a woman and an immigrant in a period when women were not well accepted in science. She is an example of a woman who survived jealousy, ignorance, disbelief, and lack of support. Very few people believed in her, except the man who fell in love with her: her co-worker and later her husband, Pierre Curie. The time and environment were not the best conditions for an immigrant woman to succeed in science. She had the strength to never give up on her true passion—science. She ended up being the only person in the world to have received two Nobel Prizes.

What is your favorite brain structure?

The thalamus. All sensory information goes through the thalamus. It is a fascinating structure that underlies perception, attention, and consciousness—the essential ingredients of our every day life. My lab studies how the thalamus affects these roles and how damage to the thalamus affects the brain and leads to epilepsy and psychiatric disorders.

Inside the Brain: Tackling Neurological Disease at Its Roots

Inside the Brain: Tackling Neurological Disease at Its Roots

For World Brain Day, discover some of Gladstone’s latest breakthroughs in neurological research.

Gladstone Experts Research (Publication) Alzheimer’s Disease COVID-19 Parkinson’s Disease Neurological Disease Akassoglou Lab Corces Lab Huang Lab Mucke LabStem Cell Therapy Jumpstarts Brain Recovery After Stroke

Stem Cell Therapy Jumpstarts Brain Recovery After Stroke

Gladstone scientists showed that modified stem cells can improve brain activity, even when administered more than a month after a stroke.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Paz LabGladstone Grad Student Shines on International Neuroscience Stage

Gladstone Grad Student Shines on International Neuroscience Stage

In early 2024, Deanna Necula co-chaired a prestigious Gordon Research Seminar in Ventura, California

Postdoctoral and Graduate Student Education and Research Development Affairs Graduate Students and Postdocs Neurological Disease Paz Lab