Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

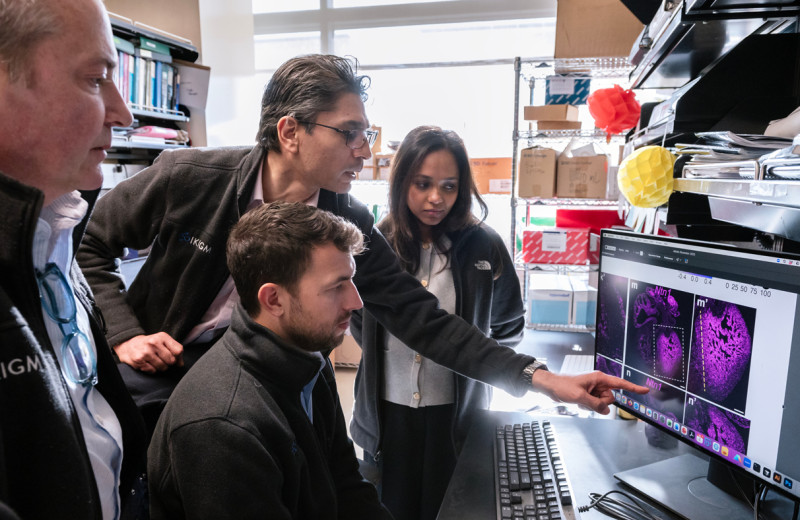

In collaboration with researchers from Emory University and UC San Francisco, Nadia Roan (right) helped discover that the presence of autoantibodies in the nose can help fight off COVID-19 more effectively.

A wide variety of COVID-19 symptoms exist, ranging from mild to severe. And while current strains of the virus generally cause milder symptoms, those with co-morbidities are still at an exponentially greater risk of severe disease. Now, new research from Emory University, in collaboration with scientists at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco, is providing a more precise prediction of COVID-19 severity by looking at autoantibodies in the nasal cavity, which could lead to more personalized treatment plans.

For high-risk individuals, this could provide critical data to inform immediate treatment options, including quickly taking medications like Paxlovid within one week of symptoms to mitigate a severe response.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, followed 125 patients with varying levels of COVID-19 (from mild to severe) for nearly two years. They tracked antibodies in both the blood and nasal airways, finding that more than 70 percent of people with mild or moderate COVID-19 developed certain autoantibodies—antibodies intended to attack the person’s own body and that are generally an indication of disease—in the nose that were surprisingly linked to fewer symptoms, better antiviral immunity, and faster recovery.

The findings suggest that the presence of autoantibodies in the nose can play a protective role and help regulate the immune system to prevent excessive inflammation and fight off the virus more effectively.

“Generally, autoantibodies are associated with pathology and a negative prognosis, causing increased inflammation that would indicate more severe disease,” says Eliver Ghosn, PhD, senior author on the paper and faculty member of the Lowance Center for Human Immunology and Emory Vaccine Center. “What’s interesting about our findings is that with COVID-19, it’s the opposite. The nasal autoantibodies showed up soon after infection, targeting an important inflammatory molecule produced by the patient’s cells. These autoantibodies latched on to the molecule, likely to prevent excessive inflammation, and faded as people recovered, suggesting the body uses them to keep things in balance.”

“It was fascinating that autoantibodies against interferon seem to be part of the ‘normal’ immune response in the nasal mucosa, as a way to help shut down an immune response when it’s no longer needed,” says Gladstone Senior Investigator Nadia Roan, PhD, who collaborated on the study. “I think it will be interesting in future studies to study whether the inability to properly do this can lead to diseases associated with chronic inflammation, such as Long COVID.”

Previous studies on COVID-19 patients have suggested that autoantibodies in the blood predispose them to life-threatening disease. However, these studies often neglect the nose, the actual site of infection. The new study suggests that the immune responses mounted in the nose against the virus differ from those in the blood. In short, nasal autoantibodies equal protection, whereas autoantibodies found in the blood equal severity.

“The key to this puzzle was to look directly at the site of infection, in the nose, instead of the blood,” says Ghosn. “While autoantibodies in the blood were linked to bad prognosis, producing them only in the nose soon after infection is linked to efficient recovery.”

A More Efficient Diagnostic Tool

To allow more precise measurements of antibodies produced locally in the nasal site of infection, the Ghosn lab developed a new biotechnology tool called FlowBEAT to quantify different types of antibodies in nasal cavities and other biological samples, which could soon have implications for the testing of other respiratory viruses, like flu or RSV.

“Historically, the technology to measure antibodies has low sensitivity and is inefficient since they are limited to measuring one or a few antibodies at a time,” says Ghosn. “With FlowBEAT, we can take any standard nasal swab and perform a combination test to simultaneously measure all human antibody types against dozens of viral and host antigens in a single tube—a much more sensitive, efficient, and scalable way to measure for autoantibodies in the nose that can also predict the severity of symptoms.”

Next, the researchers wanted to find out whether this surprising mechanism to control COVID-19 infection in the nose also plays a role in other respiratory infections like flu and RSV.

“If this nasal autoantibody response turns out to be a common mechanism to protect us against other viral infections, it can be a paradigm shift in how we study protective immunity,” says Ghosn. “We will interpret autoantibodies through an innovative lens, hopefully inspiring new lines of research and better therapeutic options for common respiratory infections.”

Featured Experts

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Disrupted Boundary Between Cell Types Linked to Common Heart Defects

Gladstone scientists identified a cellular boundary that guides heart development and revealed how disrupting it can lead to holes in the heart’s wall.

News Release Research (Publication) Congenital Heart Disease Cardiovascular Disease Bruneau LabGene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Gene Editing Strategy Could Treat Hundreds of Inherited Diseases More Effectively

Scientists at Gladstone show the new method could treat the majority of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

News Release Research (Publication) Neurological Disease Conklin Lab CRISPR/Gene EditingGenomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Genomic Maps Untangle the Complex Roots of Disease

Findings of the new study in Nature could streamline scientific discovery and accelerate drug development.

News Release Research (Publication) Marson Lab Genomics Genomic Immunology