Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Will Flanigan explains where his interest in science stemmed from and how his favorite part of graduate school is showing his friends what he's working on

Will Flanigan (he/him) is a third-year PhD student in the UC San Francisco/UC Berkeley joint graduate program in bioengineering and is co-advised by Isha Jain, PhD, and Seth Shipman, PhD. Previously, he studied biomedical engineering and biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. During that time, he worked in two research labs, studying symbiotic relationships between insects and bacteria and using tissue models to study early metastasis events in ovarian cancer. Here at Gladstone, Flanigan is excited to use stem cells to understand how the heart responds to a drop in oxygen.

What brought you to Gladstone?

I was first drawn to Gladstone by the student community here, especially within the McDevitt Lab—the first lab of my thesis work. The graduate students here have their own organization called Gladstone GO, and we put on a lot of programming to bring students together. It’s really this lively and supportive group of students that makes me excited to come to work every day.

What do you like about Gladstone?

Gladstone is a great place to work. I love how connected I feel with the scientists in my research group and on my floor. Each institute has frequent seminars and happy hours that facilitate collaboration, and the team projects I’ve been a part of have been some of the most rewarding.

I also appreciate how Gladstone as an organization is very vocal with their mission statement and they make it apparent that they value the diversity of the personal identities within the building.

Can you describe your current research project?

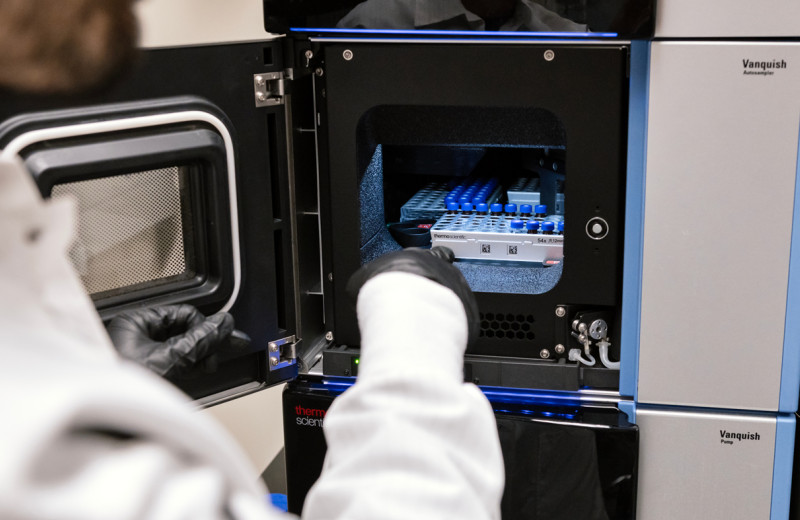

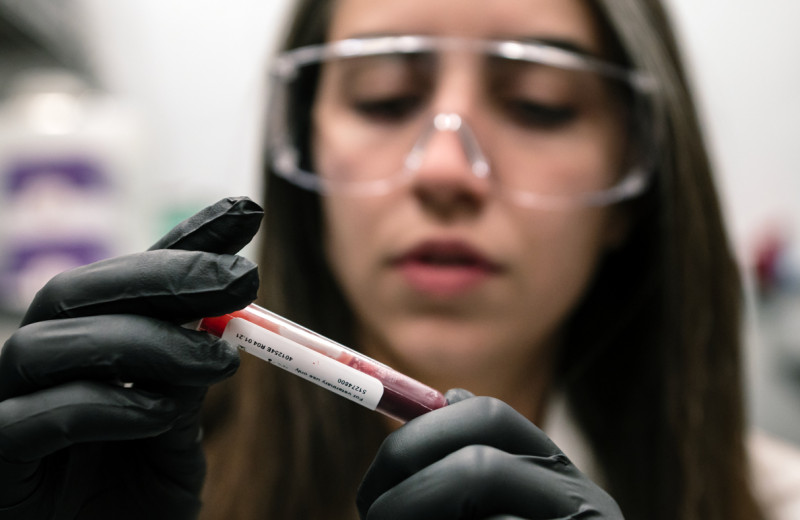

I study how the heart responds to low oxygen—called hypoxia—in an effort to design therapies to protect the heart from hypoxic damage. Hypoxia can occur during a heart attack or because of a congenital heart disease (something that affects babies), so it’s a huge cause of heart damage. To model this, I use stem cells to create heart cells in a dish, and then place those heart cells in special chambers to limit their oxygen supply and study their response.

Were you interested in science as a child?

I think I was mostly just curious about how things worked. I have a fond memory of watching construction sites for hours as a young child. My dad and I would pack a lunch for the day and take a bus downtown to watch cranes add pieces to a building. I’ve always been fascinated at how things are put together, and that continues in my current work, just on a much smaller scale. The same type of simple questions I asked as a kid drive my research today: What are the pieces that make up a heart cell and how do they all work together? What happens if a piece in the cell breaks? Does it cause heart disease and if so, can we fix it?

How did the pandemic change your work?

Early in the pandemic, our group pivoted efforts to study how SARS-CoV-2 infects cardiac cells and affects heart tissue. This was a really fun project and it was a privilege to work with a team across many labs at Gladstone. I worked remotely for several months, but since stem cells require frequent maintenance, I’ve been coming to Gladstone for most of the pandemic.

I hope we continue our safe return to gathering because I miss some of the busyness and buzz at Gladstone from the pre-pandemic days.

What do you do when you are not working?

Most of my interests are centered around food and the outdoors. I love to explore the San Francisco Bay on my bike and find new parks for picnics. I’m a big fan of dinner parties with friends and I usually bring the charcuterie board.

What is your hidden talent?

I don’t know if this is a talent, but I have a good memory for locations and directions. I’ll often remember how to get around a neighborhood or new place, even if I’ve only been there once.

What’s your favorite part about grad school?

I love sharing what I study with friends and family. I’ll send videos to friends of heart cells beating in a dish that I made from stem cells, and their reaction often makes me remember how cool my job is. It feels a little like sci-fi sometimes, and that’s pretty neat.

Why is having a visible LGBTQ+ community in your field and at work important to you?

This is super important. Imposter syndrome is already common in STEM, and without visible LGBTQ+ role models that share your identity, it can be difficult to feel like you belong or deserve to be in that space. I think it’s especially important for organizations to openly show support for their LGBTQ+ members, because silence on the matter is often internalized as discouragement for self-expression.

We have come a long way—even just within my lifetime—but we still have a lot of work to do. Especially now with recent increases in hate crimes and legislation against our community, we will not be done until every LGBTQ+ individual feels safe and confident that their identity matters.

Want to Join the Team?

Our people are our most important asset. We offer a wide array of career opportunities both in our administrative offices and in our labs.

Explore CareersVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabRed Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

Red Blood Cells Soak Up Sugar at High Altitude, Protecting Against Diabetes

New study shows red blood cells act as hidden glucose sponges in low-oxygen conditions, explaining why people living at high altitude have lower diabetes rates and pointing toward new treatments.

News Release Research (Publication) Diabetes Jain LabGladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

From fundamental insights to translational advances, here’s how Gladstone researchers moved science forward in 2025.

Gladstone Experts Alzheimer’s Disease Autoimmune Diseases COVID-19 Neurological Disease Genomic Immunology Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Infectious Disease Conklin Lab