Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Since the launch of the program in 2021, Gladstone has recruited nine scholars through the Embark program as a way to address lack of diversity in the STEM workforce.

In 2020, Gladstone had a significant lack of diversity among its postdoctoral researchers, with only 4 percent of postdocs identifying as Hispanic or Latinx, and no Black postdocs. These numbers reflect the broader issue of underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic workers in the life sciences, as they make up only 6 and 8 percent of workers in the field respectively, despite representing a larger percentage of the total workforce.

The same year, after the wave of social unrest that heightened awareness of racial equity in the United States, Gladstone Institutes launched its plan to focus on and improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within the organization.

“Ever since its founding, Gladstone has always stood for the highest ideals of science in the service of humanity,” says R. Sanders Williams, MD, former president of Gladstone. “Events from the past few years that brought more direct focus on persistent structural racism in our country have led me and many others to think that even though we've always been well-meaning, what we’ve done in the past is not enough.”

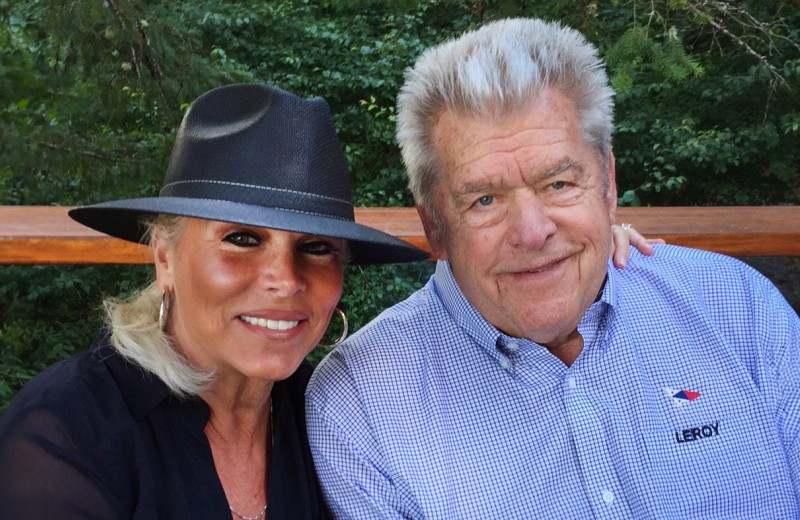

Williams and his wife Jennifer were among the first donors to support Gladstone’s Presidential Postdoctoral Program, Embark—a key initiative of Gladstone’s DEI strategy. Together with donors David and Mary Phillips, they pledged significant funds to support this program, which aims to hire postdocs from backgrounds that are traditionally underrepresented in the sciences.

When they join Gladstone’s tailored mentoring program, Embark scholars receive a $10,000 annual stipend, in addition to the other support provided to all postdocs.

“Postdocs have a lot of financial burdens, especially when it comes to moving to San Francisco, so this program helps attract people from a variety of racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds," says Embark Scholar Bria Macklin, PhD. “Often, organizations say they are committed to diversity, but they don’t actually put any action behind it. Here, they said ‘let’s increase the diversity of postdocs’ and then actually went out and created an initiative to do so.”

Candidates from all over the world interview to train at Gladstone, and the financial support can often be the encouragement a researcher needs to make the plunge to move to a new city. Oluwole Alese, PhD, who is originally from Nigeria and studied in South Africa, was drawn to Gladstone by the advanced technologies available there.

“It was a huge transition for me, but I’m very grateful for the people at Gladstone,” says Alese, who studies Parkinson’s disease in Ken Nakamura’s lab. “The funding that Gladstone provides has really helped me set up my accommodations and get acclimated here.”

“I’m so pleased that Embark has already been a great success,” says Gladstone President Deepak Srivastava, MD. “I’m also thankful for the generous support of the Williams and Phillips families, which has allowed us to launch and sustain this program. By bringing together early-career scientists from around the world and providing them with mentorship, resources, and a collaborative environment, we can accelerate progress and push the boundaries of what is possible in science.”

Increasing Diverse Viewpoints

For the Phillipses, a primary goal in supporting the Embark program is to provide increased opportunities for individuals from underrepresented backgrounds to develop their careers, become role models, and become leaders both in their fields and in their organizations.

Embark Scholars with Donor David Phillips from left to right: Jonathan Meng, Rosmely Hernandez, Dennis Tabuena, David Phillips, Unekwu Yakubu, Alicer Andrew, and Oluwole Alese.

“Fulfilling this goal not only impacts the individual scientists, but will also allow biomedical research to impact a broader spectrum of the world’s population,” says David Philips.

Phillips’s own experience has shown him just how important it can be to have a variety of viewpoints in the room. His research career has focused on understanding the function of blood cells and other blood components. In the 1980s, his lab at Gladstone identified a molecule at the surface of platelets that causes this type of blood cell to clump together and form blood clots.

Subsequently, he co-founded three biotech companies: COR Therapeutics, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Global Blood Therapeutics. The latter developed Oxbryta, a drug launched in 2019 to treat sickle cell disease.

Despite sickle cell disease impacting 1 out of every 365 African Americans in the United States, Oxbryta was only the third drug developed for this disease. Phillips thinks this is likely due to the lack of diversity in the decision-making process within the pharmaceutical industry—an unfortunate reality that has a big impact on delivering healthcare.

“As indicated by our sickle cell experience, everyone would have benefitted from having a more diverse group of leaders shape decisions on research, drug discovery, and development many years ago,” says Phillips. “You need to have people of color move up through the ranks in order to make problems apparent and contribute to decisions on where the research should go next. The Embark program is designed to allow individuals from minoritized groups opportunities to proceed in that direction and become positioned to impact the many, diverse diseases.”

Creating a Community

For program manager Sudha Krishnamurthy, PhD, it was important that the support provided by the Embark program went beyond monetary.

“We’ve been committed to creating an enriching environment that includes strong mentorship, peer support, and community building along with the monetary support,” says Krishnamurthy, director of postdoctoral and graduate student education and research development at Gladstone.

This aspect of community building has been essential for incoming Embark scholars.

“Programs like Embark are really important because as a person of color, when you’re joining a new organization, you don’t always know what the environment is going to be like—if it’s supportive, if you can thrive there,” says Macklin, who works on increasing the efficiency of gene editing tools for conditions like ALS and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

The Embark program provides a collaborative research environment, career and professional development opportunities, community building, and personalized mentoring programs. Seen here is Embark Scholar Bria Macklin working in the lab.

“It can take a lot of guesswork to sleuth that out,” she adds. “When an institution takes a very clear stance about how they’re going to support their postdocs from minoritized groups, it makes you realize, as a prospective trainee, that you’ll be supported in that environment.”

Embark scholars regularly meet and connect with each other. That was a big draw for Rosmely Hernandez, PhD, who was born in Cuba and has spent the majority of her academic career close to her family; first college near her parents in Alabama and then graduate school near her grandmother in Miami. As she was looking to expand her scientific skills, she decided to take the plunge to join Alex Marson’s lab and move to San Francisco—a place where she had no familial connections.

“There’s a huge sense of community here at Gladstone, particularly among Embark scholars,” says Hernandez. “I feel super comfortable here. There’s so much collaboration going on and it’s easy to go to other people and ask advice on an experiment or their opinion on papers that have been published. You just feel like you’re at home and you don’t worry about asking questions because you’re not going to be judged. Everyone is ready to help.”

Being a Trendsetter

While Embark is specifically focused on increasing racial and ethnic representation within Gladstone’s walls, the hope is that it will also encourage other organizations to take action of their own.

“It’s my aspiration that other organizations would attempt to mirror Embark because we’ve set a trend,” says Williams. “Gladstone isn’t just a player in the medical discovery field, we’re leaders. Every Gladstone investigator stands out in their subfield, and therefore, we attract attention. And we want to bring attention to doing the right thing in every dimension of how excellent science is performed.”

Embark Scholars from left to right: Dennis Tabuena, Ifeanyi Ezeonwumelu, Bria Macklin, Unekwu Yakubu, Rosmely Hernandez, and Jonathan Meng.

Dennis Tabuena, PhD, a San Francisco Bay Area Native, has participated in several programs similar to Embark throughout his scientific and educational career.

“Programs like these make a huge difference,” says Tabuena, a postdoctoral and Embark scholar who works in the lab of Yadong Huang. “Bringing in a broader spectrum of people will help science penetrate new layers of society that could really benefit from it. One of the most important things, I think, is to help people understand how the work that we're doing can also help them in their lives.”

Since the launch of the program in 2021, Gladstone has recruited nine Embark scholars who are all working to better understand, treat, and ultimately end diseases ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to cancer.

“While we had never excluded anybody, we hadn’t been as proactive about going out and finding a diversity of postdoctoral candidates,” says Williams. “But Embark is Gladstone’s way of being active, and not just passively welcoming in this arena.”

Gladstone’s DEI strategy acknowledged that the organization has a lot of work to do to ensure that Gladstone’s community accurately represented the country’s population. Embark is one of the steps to help accomplish this goal.

“The lack of diversity in STEM is a critical issue that must be addressed,” says Srivastava. “By providing opportunities and support for individuals from underrepresented backgrounds, we can help break down barriers and create a more diverse and inclusive scientific community that reflects the true diversity of our society.”

Featured Experts

Want to Join the Team?

Our people are our most important asset. We offer a wide array of career opportunities both in our administrative offices and in our labs.

Explore CareersEmbracing Change: Darlene Hines Shares Her Journey of Growth, Resilience, and Giving Back

Embracing Change: Darlene Hines Shares Her Journey of Growth, Resilience, and Giving Back

Longtime Gladstone supporter Darlene Hines reflects on her journey of learning, growth, and giving after her husband’s passing

Donor StoriesVisionary Philanthropists Establish Center to Harness Computational Biology for Cancer Research

Visionary Philanthropists Establish Center to Harness Computational Biology for Cancer Research

A search for the brightest minds in cancer and AI led Hope and Sanjit Biswas to give in their own backyard.

Philanthropy Donor Stories Cancer Biswas Center for Transformative Computational Cancer Biology Data Science and Biotechnology Pollard Lab AI Big DataThe Risk and the Reward

The Risk and the Reward

How the Dolby family works to improve outcomes for people with Alzheimer’s disease

Donor Stories Alzheimer’s Disease