Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

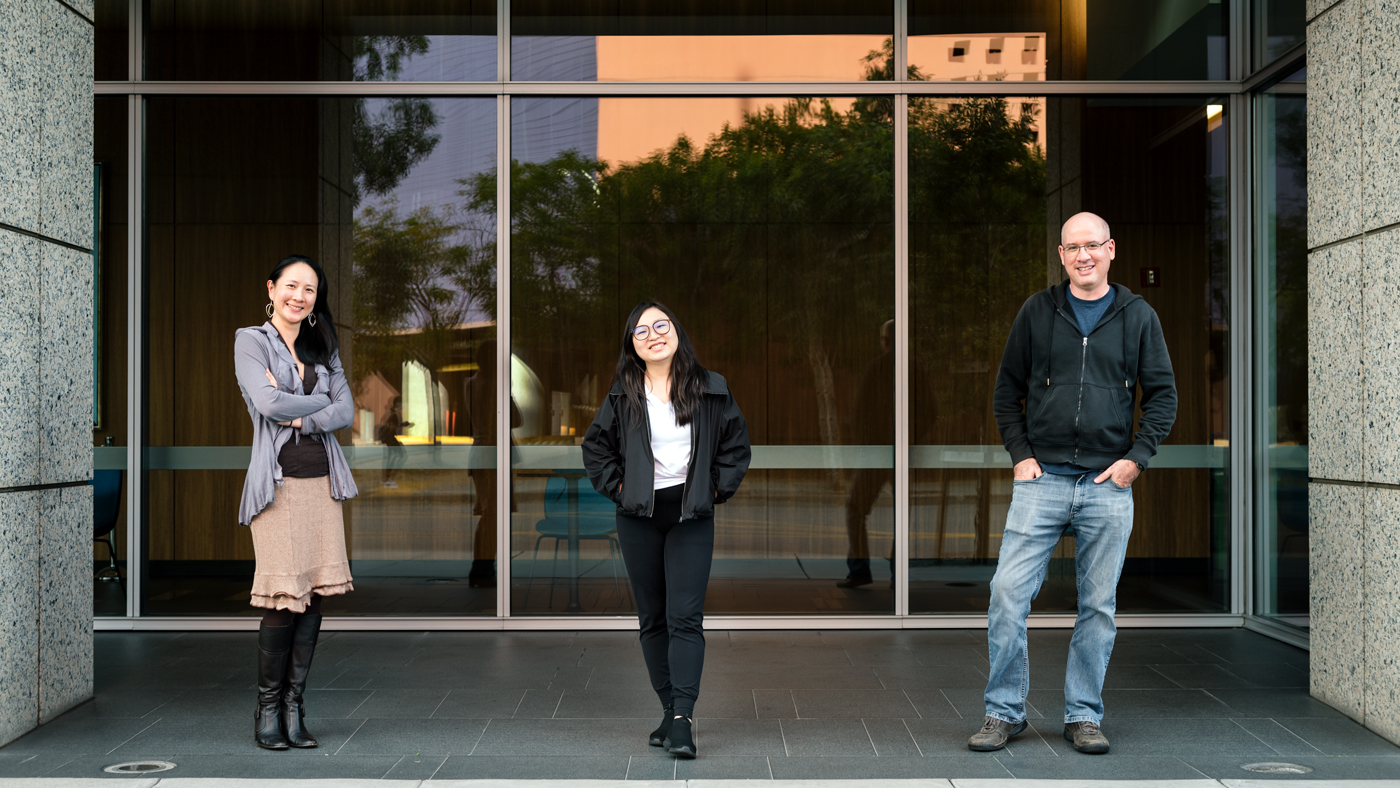

Nadia Roan and her colleagues—including Xiaoyu Luo (left) and Jason Neidleman (right), the first authors of a new study—studied how T cells respond to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines and the different variants of SARS-CoV-2.

A quick stick in the arm with an approved COVID-19 vaccine elicits a flurry of activity in the body’s immune system. While much work has been done to study the antibodies produced in response to these vaccines, less is known about the response by the immune system’s T cells, which offer longer-term protection against the virus. Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes have carried out a detailed survey of T cells before and after COVID-19 immunization.

The team concludes, in the scientific journal eLife, that both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines lead to the generation of long-term populations of T cells that can recognize multiple variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. But they also identified key differences in the T cell responses of individuals who had been infected with COVID-19 prior to vaccination compared to those who had never been infected.

“Overall, our data support the idea that vaccines are eliciting a very robust T cell response in healthy individuals,” says Gladstone Associate Investigator Nadia Roan, PhD, senior author of the study. “But they also suggest there may be some ways to improve them further, by getting more of the vaccine-elicited T cells to park themselves in the respiratory tract.”

Nadia Roan (left), Xiaoyu Luo (center), and Jason Neidleman (right) identified exactly which subsets of T cells are able to recognize, and actively destroy, virus-infected cells before and after vaccination.

T Cell Quality, Not Quantity

The human immune system has two main arms that help fight returning infections. Antibodies produced by the immune system’s B cells can quickly recognize a virus, target it for destruction, and prevent infection. T cells, on the other hand, identify and destroy already infected cells. While antibodies are more effective at stopping initial infection completely, T cells generally last longer after an initial infection or vaccine and can help quell disease in its early stages, preventing severe symptoms.

T cells, however, are notoriously diverse and difficult to study. Distinct subsets of T cells respond differently to infected cells and have different functions within the overall T cell response. The limited studies that gauged how T cells respond to COVID-19 infections or vaccines have for the most part lumped all T cells together, quantifying the number of total T cells that recognize SARS-CoV-2. But Roan’s group wanted more detail.

“It’s not just the number of T cells that matter; It’s the quality—whether the T cells are the type that can actively destroy virus-infected cells,” says Roan, who is also an associate professor of urology at UC San Francisco.

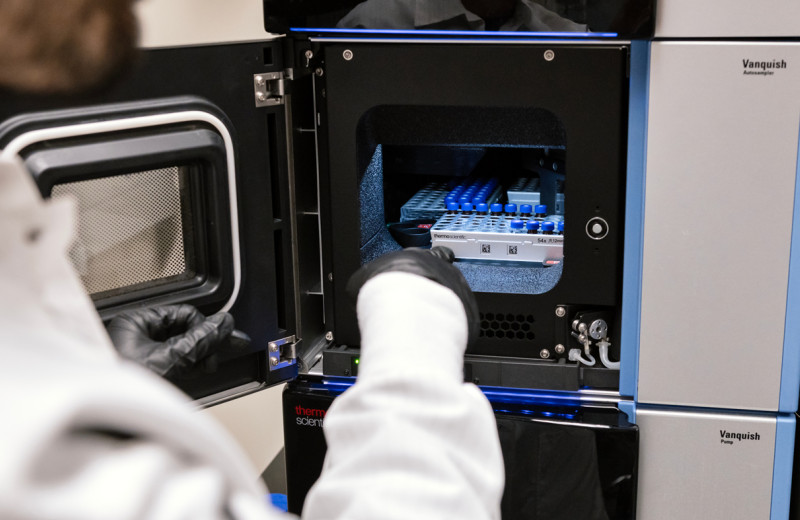

Xiaoyu Luo, a scientist at Gladstone, helped study blood samples from people who had received an mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.

Roan turned to a technology called CyTOF that can measure the levels of nearly 40 different proteins on the surface and inside of T cells. This let her and her colleagues identify exactly which subsets of T cells were able to recognize SARS-CoV-2 before and after vaccination.

The researchers used the approach to study blood samples from 11 people who had received an mRNA vaccine (either Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna) against SARS-CoV-2. Blood samples were collected from each individual before vaccination, approximately 2 weeks after their first vaccine dose, and approximately 2 weeks after their second dose. Six of the individuals had also previously recovered from mild COVID-19.

Vaccine Protection Verified

Roan’s group found that all fully vaccinated individuals in the study had T cells that responded to three different variants of SARS-CoV-2—the ancestral virus first detected in Wuhan, China; the B.1.17 variant first detected in the United Kingdom; and the B.1.351 variant first detected in South Africa. The Delta variant of the virus was not included in the new paper but Roan is currently analyzing data on it.

In people who had never been infected with SARS-CoV-2, Roan and her colleagues found that the T cell response became stronger—in both quantity and quality of T cells—after the second vaccine dose. However, in those who had previously had a COVID-19 infection, there was little change between the first and second dose of the vaccine.

“This doesn’t necessarily mean there is no benefit to a second dose in convalescent individuals,” points out Roan. “It means there is no additional effect on T cells in ways that we could capture, but there may still be other effects on the immune system, such as within B cells, after the second dose.”

The study by Jason Neidleman (left), Nadia Roan (right), and their colleagues suggests there may be ways to improve current COVID-19 vaccines.

The researchers also found that, while all individuals had a robust T cell response, T cells from those who had previously contracted COVID-19 had molecular markers suggesting the immune cells could last longer and migrate more effectively to the respiratory tract.

“We wouldn’t have detected this difference if we had just quantified all the T cells,” says Roan. “But CyTOF allowed us to pick up on these key functional differences in T cells in people who had been previously infected.”

The potentially more effective T cell defense in the respiratory tract may explain why breakthrough infections are less frequent in people with a prior COVID-19 infection compared to other vaccinated individuals. The new data, Roan says, also suggest that improving the ability of T cells to migrate to the respiratory tract after vaccination may improve the effectiveness of vaccines at preventing breakthrough infections.

Roan and her colleagues are also planning additional studies to investigate T cell responses after COVID-19 vaccination in immunocompromised people, T cell responses after booster vaccines, and how T cells behave in cases of long COVID-19, when symptoms of the virus continue for more than 12 weeks.

“Other researchers are looking at antibodies in all these instances, and it’s certainly not the case that antibodies aren’t important, but we can’t forget about T cells,” she says.

For Media

Julie Langelier

Associate Director, Communications

415.734.5000

Email

About the Study

The paper “mRNA vaccine-induced T cells respond identically to SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern but differ in longevity and homing properties depending on prior infection status” was published in the journal eLife on October 12, 2021. Other authors are Jason Neidleman, Xiaoyu Luo, Matthew McGregor, Guorui Xie, and Warner Greene of Gladstone; and Victoria Murray and Sulggi Lee of University of California, San Francisco.

The work was supported the Van Auken Private Foundation; David Henke; Pamela and Edward Taft; the Roddenberry Foundation; the Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, which is partly funded by the Sandler Foundation; and Fast Grants, a part of Emergent Ventures at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University (Awards #2164, #2208 and #2160).

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

Featured Experts

Support Our COVID-19 Research Efforts

Gladstone scientists are moving quickly to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. Help us end this pandemic.

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

New Tool Reveals the Secrets of HIV-Infected Cells

Developed by Gladstone scientists, HIV-seq could uncover new opportunities for treating HIV.

News Release Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabVitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

Vitamin B3 Therapy Offers Hope for Fatal Childhood Disease

A new framework that matches vitamins with genetic diseases helped uncover that high-dose vitamin B3 can dramatically extend survival in mice with NAXD deficiency.

News Release Research (Publication) Rare Diseases Jain LabGladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Gladstone Scientist Nadia Roan Elected to American Academy of Microbiology

Roan has made great strides in understanding how persistent viruses including HIV cause disease and how immunity to viruses shapes human health.

Awards News Release COVID-19 HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab