Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

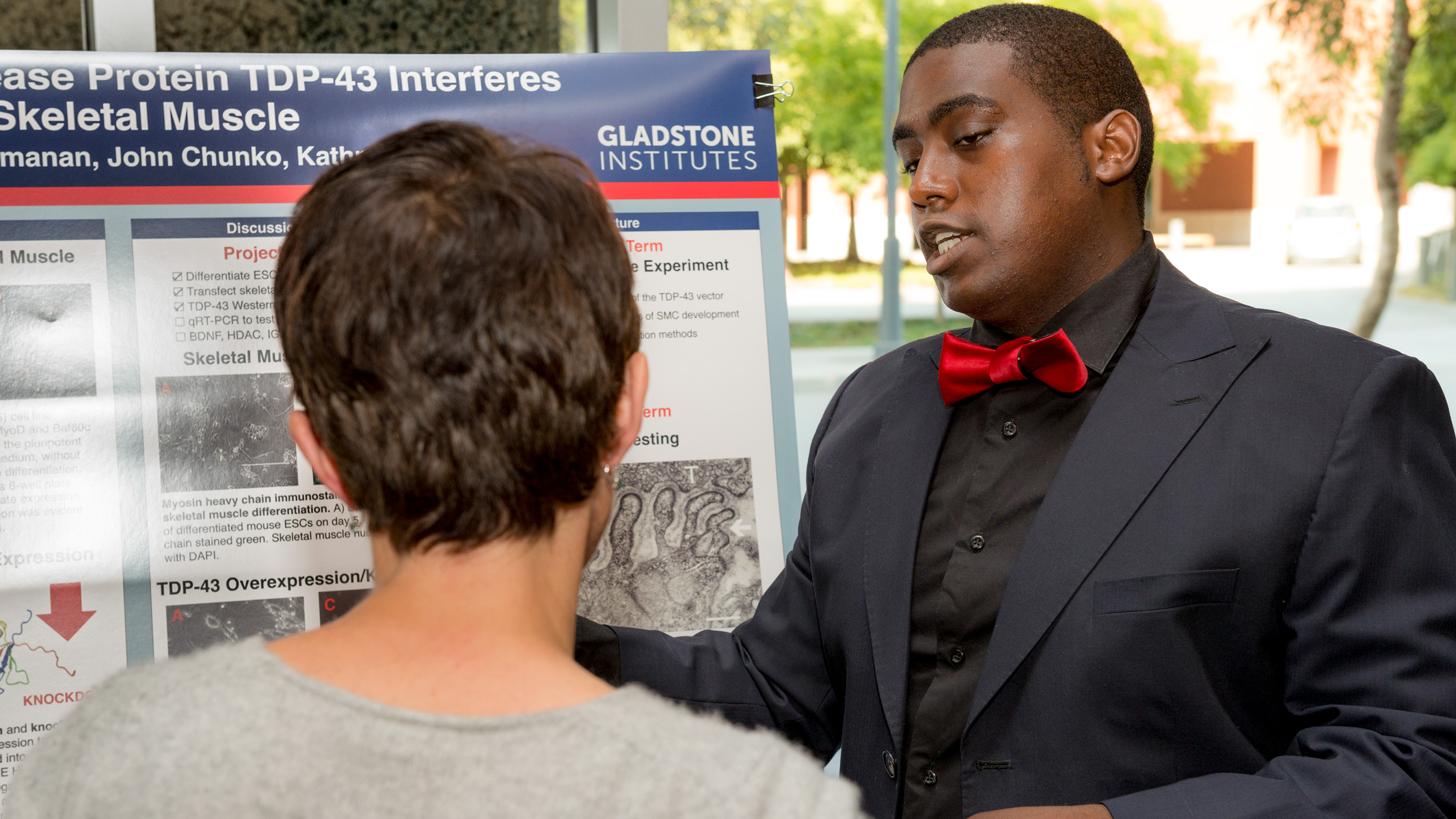

Damon Williams reflects on how two summers at Gladstone changed his career trajectory

As an undergraduate student, I loved science and dreamed of becoming a physician, but I didn’t have a clear sense of the career path that would get me there. Then, I got a taste of the lab life as an intern in the PUMAS (Promoting Underrepresented Minorities Advancing in the Sciences) program at Gladstone Institutes during the summers of 2014 and 2015. The PUMAS program is a biomedical research internship program where undergraduates majoring in science work closely with mentors on projects aimed at understanding or curing unsolved diseases. Now, I’m working full time in a lab, and aspire to one day lead my own research group and discover new ways to fight cancer.

Immersed in a Whole New World

I remember being completely mind-blown the first time I walked into a lab at Gladstone. I was overwhelmed with joy and a sense of belonging that I’d never felt before. I was surrounded by machines, busy scientists working on experiments, people in lab coats and goggles, and shelves lined with chemicals. I was curious to learn what every little machine and gadget was used for, and how they’d help me make scientific discoveries.

I was surprised to see how many people worked in the lab, and how social they were with each other. I’d heard rumors that research can be lonely and isolating, but that wasn’t what I experienced at Gladstone. Beyond the day-to-day conversations about work, there were also lab mixers where the members would socialize over cheese and cider. I even had the opportunity to briefly chat with Nobel laureate, Shinya Yamanaka!

Attending my first lab meeting was both terrifying and wonderful. As I watched the scientists in my lab present their research on heart development, I felt overwhelmed and lost. Although I didn’t know much of what they were speaking about, I was excited to go home and look up the unfamiliar terms. Little did I know that the things being discussed in these lab meetings would be extremely valuable in helping me study for exams when I returned to the classroom. My undergraduate biology curriculum revolved around fundamental and modern research techniques, and my experience at Gladstone provided me with crucial background knowledge for those classes, leading to better test scores. In fact, sometimes my peers thought I was cheating because I had so much practical knowledge from my time at Gladstone.

Combining What I Loved

My mentor told me that the title of my first project was: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Disease Protein TDP-43 Interference with MiR-1 Incorporation into the RNA-induced Silencing Complex in Mouse Skeletal Muscle. That was a lot of words I was unfamiliar with. However, I came to understand that I was trying to figure out how and why a certain protein (TDP-43) stopped a certain RNA (MiR-1) from behaving the way it should in animals with the lethal neurodegenerative disease Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. ALS patients often die because the muscles they use to breathe stop working; if I could help figure out what drove this dysfunction at the level of the molecules involved, other scientists might use that information to design a new therapy.

Working with cells to study a deadly disease was the perfect combination of science and medicine for me. I enjoyed the hands-on lab work of dealing with live cells, and was motivated by the idea that my work could someday have clinical applications. Also, working on my project allowed me to discover the areas of research I really enjoy doing (regenerative medicine and stem cell biology), and the ones I don’t (working directly with animals).

Damon Williams was a PUMAS intern in 2014 and 2015.

When I applied to the internship, I thought I should become a physician, because I enjoy helping people and want to develop new therapies. At the time I believed that you had to be a physician to do so. As the internship progressed, I learned that the individuals at the forefront of drug discovery and development were often not physicians, but lab scientists. I realized that if I became a science doctor (PhD) instead of a medical doctor (MD), I could experience the thrill of scientific discovery and my work could help patients indirectly by leading to the discovery of new medicines. My path was now set.

Weekly Seminar Sessions

On top of learning how to do experiments and gaining the invaluable experience of working in the lab, the PUMAS program included weekly seminars that taught me the business side of science, and how to conduct myself both in and outside the lab. The seminars provided us with a comprehensive understanding of what it is truly like to be a scientist, and included topics, such as ethics, funding, project management, work/life balance, and networking. As someone with no prior lab or research experience, it was eye-opening to learn about the non-science things that go into a successful science career.

Some of the seminars included panels of working professionals who shared their real-life experiences. We learned about some of the ethical dilemmas that scientists can face, and the steps we can take to ensure our scientific integrity. We met with Gladstone’s scientific editors and heard about the importance of having strong oral and written communication skills, as well as scientific career opportunities that don’t involve doing experiments.

A Taste of Reality

The internship also prepared us for some of the realities we will face in our future careers. For example, I learned about the intense pressure that biomedical scientists can face to publish their work. Simply put, if you can’t publish your science in an academic journal, you will probably not be successful, either in raising money to support future work or in progressing to the next career stage in academia. This “publish or perish” culture can drive some aspiring scientists out of the field.

Another part of research that is challenging is the constant need for funding, which forces scientists to devote a lot of time to writing grants instead of focusing on their experiments. And as grant funding becomes increasingly competitive, scientists can feel stuck—they need grant funding to perform experiments, but they can’t get grant funding unless their preliminary experiments have worked and show promise.

I am thankful, however, to have seen early in my career how challenging this path can be. Being surrounded by many successful scientists who have thrived despite these obstacles helped reassure me that it was possible. Also, I realized that I shared the passion for discovery that is necessary to be successful in the biomedical research field.

A Caring Community

My favorite part of the PUMAS internship was working with my colleagues at Gladstone. All of them were welcoming, humble, and polite. It was great knowing that I could go into the break room and have a deep conversation about science, a shallow conversation about the San Francisco weather, or anything in between. In addition, the collaborative nature of research makes the work more fun, because you can speak to so many different people about what you’re doing and any difficulties you’re facing.

The leaders of the PUMAS program were instrumental in making the internship experience as good as it was. They genuinely cared about us and went out of their way to make our time at Gladstone impactful. Working with the staff and investigators at Gladstone also increased my professionalism by inspiring me to carry myself and behave in the ways modeled by my colleagues.

In Hindsight

Before the internship, I was a typical pre-med undergraduate community college student who enjoyed biology. I aspired to be a physician, but hadn’t the slightest clue of how I’d get there, and was simply going through the motions. The PUMAS program helped me discover that a career in biomedical research would combine two things I loved—science and medicine. Gladstone’s PUMAS program is without a doubt the most valuable career development experience I’ve had. The connections I made, the knowledge I gained, and the lab experience I received from the program are what landed me my current position as a researcher at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, and what molded me into the working professional I am.

All of these experiences contributed to making my PUMAS internship incredibly memorable. I recommend the PUMAS program to any undergraduate STEM student that would like to get a good taste of what the biomedical research life is like, and I hope that the experience is as valuable for them as it was for me.

Want to Join the Team?

Our people are our most important asset. We offer a wide array of career opportunities both in our administrative offices and in our labs.

Explore CareersMeet Gladstone: Alisa Dietl

Meet Gladstone: Alisa Dietl

Alisa Dietl brings her international training and clinical perspective to Gladstone, where she works to engineer more effective cancer immunotherapies for solid tumors.

Graduate Students and Postdocs Profile Cancer Pelka LabVoices of Outstanding Mentorship

Voices of Outstanding Mentorship

Three recipients of Gladstone’s Outstanding Mentoring Award share their personal approaches to mentorship and reflect how this passion has shaped their own growth as leaders.

Profile Roan Lab Graduate Students and PostdocsMeet Gladstone: Shyam Jinagal

Meet Gladstone: Shyam Jinagal

Shyam Jinagal explores how genetics, aging, and regeneration shape the heart—and how those insights could one day restore heart function after injury.

Graduate Students and Postdocs Profile Cardiovascular Disease Srivastava Lab