Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

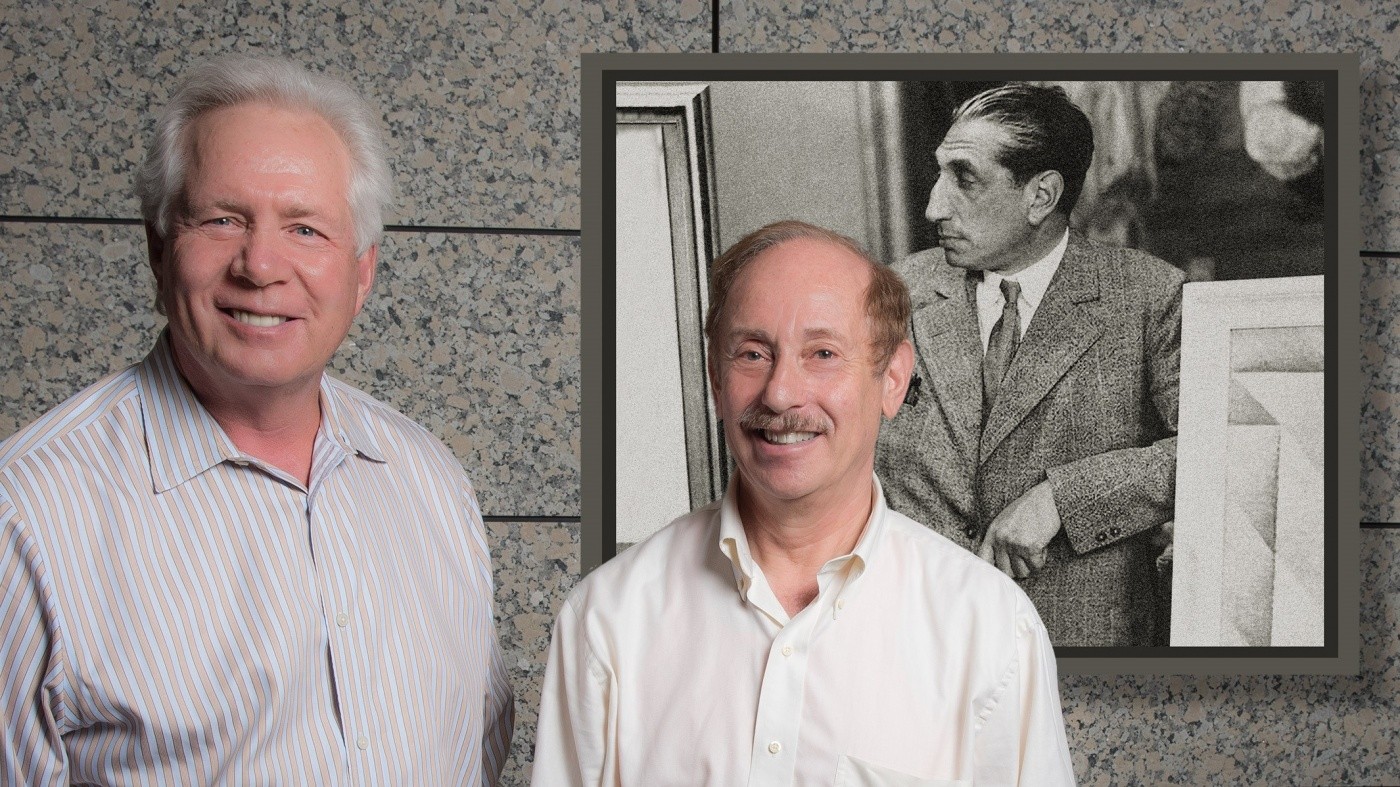

Warner Greene, MD, PhD, and Mike Hulton, MB, BChir have dedicated their lives to fighting HIV/AIDS. For Hulton, this includes donating the war reparations owed to his great-uncle Alfred Flechtheim (pictured), a legendary art dealer targeted during Nazi Germany, to AIDS research. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow, Gladstone Institutes]

Life has been full of surprises for anesthesiologist Michael Hulton, MB, BChir. The son of a German-Jewish refugee who fled Berlin in the early 1930s to escape the terror of the Nazi regime, Hulton certainly never expected to become the heir to an extraordinary art collection worth millions or to serve as a pioneer in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Born in London in 1946, Hulton rarely thought about his family’s experiences during the Nazi era in Germany. “I never really dwelt on the Nazi past; like many children who had not lived through that horror, I felt like it was a topic from my parents’ time,” explains Hulton.

Hulton carried on with his life, “minding my own business,” as he says. He did well in his studies, earning a medical degree from Cambridge University in 1970. He later completed a residency in anesthesia in Toronto, as well as a fellowship at Stanford, before becoming a practicing anesthesiologist in Canada in 1979.

Then, the HIV/AIDS epidemic struck in the early 1980s. “Great numbers of people—initially gay men—were dying off from this disease, while the rest of society carried on indifferently, and various governments denied the existence of AIDS,” remembers Hulton. “For me, there were far too many similarities with the Holocaust. This was MY generation being decimated.”

This realization sparked Hulton to both investigate his own family history and get involved in the AIDS medical research community. Little did he know that the tragedy of his family’s past might one day be turned into something positive for future generations of HIV/AIDS patients.

A Fascinating Family History

Hulton’s father, Henry Hulton, had been a promising management trainee when he left Berlin. He ultimately landed in London, where the only job he could obtain was as a garment cutter.

As a child, Hulton occasionally heard his father speak of “Uncle Alfred,” whose sister-in-law was Hulton’s grandmother. Alfred had fled Nazi Germany in 1933, also eventually settling in London, where he died of an infection in 1937. In his will, Alfred named Hulton’s father as his heir.

What Hulton did not fully comprehend until later was that his great-uncle was actually Alfred Flechtheim, a legendary art dealer and publisher who had owned galleries in Berlin and Düsseldorf. Flechtheim was an early target of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party, both because he was Jewish and because he specialized in modern art, which the Nazis deemed to be “degenerate.”

After a Nazi paramilitary group forcibly broke up an auction of his paintings in March 1933, a terrified Flechtheim escaped from Germany. His galleries, which included paintings by world-renowned artists such as Max Beckmann, Paul Klee, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Renoir, were taken over by a non-Jewish former business partner. Hundreds of paintings from Flechtheim’s galleries either went missing or were sold.

Today, many works of art from the Flechtheim collection—worth an estimated $125 million—hang in top museums in Germany and elsewhere around the world.

For the past eight years, Hulton has sought to establish his family’s rights to these masterpieces. While Germany and dozens of other nations have committed themselves to returning works of art that were lost during the Nazi era for “reasons of persecution,” Hulton’s case is complicated by the fact that nearly all of the documents from Flechtheim’s galleries disappeared.

Hulton has received compensation for two paintings from his great-uncle’s collection, but the provenance of the most valuable pieces remains contested. The issue at the heart of the case is determining which of Flechtheim’s paintings were seized or sold after the Nazis took power on January 30, 1933.

This is not a battle Hulton expected to wage, nor one from which he hopes to benefit personally. “This inheritance is not something I would feel content in spending or using for my own purposes. I want justice for my great-uncle, my parents, and the many others who were persecuted during this awful time in history,” he says.

Bringing this story back full circle to the devastation of his own generation, Hulton intends to donate the proceeds from his inheritance to AIDS research.

Longtime Dedication to HIV/AIDS Patients

From the earliest days of the epidemic, Hulton kept a close eye on scientific studies dealing with HIV/AIDS and spoke often with his Canadian and American colleagues in the medical field who were treating HIV patients.

In 1985, he called the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Washington, DC, and asked if he could attend one of its scientific meetings on a therapeutic that seemed to thwart the HIV virus’ ability to replicate. The response from the NIAID: “Please join us. You will be the first doctor from Canada to do so.” The drug in question—AZT—was later approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for HIV.

Upon his return to Canada, Hulton opened a part-time medical practice in Toronto. His patients were among the first in that nation to gain access to AZT. “My aim was simply to improve the HIV/AIDS standard of care in Canada,” he says humbly.

In 1992, Hulton relocated to San Francisco, where he met many more HIV/AIDS investigators over the next 20 years.

One of these scientists was Warner Greene, MD, PhD, director of virology and immunology research at the Gladstone Institutes. In 2013, Hulton attended a presentation Greene gave on one of his lab’s recent breakthrough findings.

Soon after, Hulton made his first of several generous donations to Greene’s research. The ongoing studies in Greene’s laboratory focus on the molecular mechanisms underlying HIV pathogenesis, latency, and transmission.

Hulton also serves as a volunteer for a clinical trial led by Gladstone’s Robert Grant, MD, MPH. In this capacity, he performs physical exams of participants in the Éclair study of a potential long-acting compound that may prevent HIV. The trial is a follow-up to Grant’s Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiative (iPrEx) study, which determined that two antiretroviral medications used to treat HIV/AIDS are effective in preventing HIV in people at high risk of infection.

Reflecting on the past 30 years, Hulton says, “I get enormous satisfaction from having witnessed AIDS transform from a death sentence into a treatable—and now, preventable—condition. This has been an incredible journey for me, and I am very pleased to be able to use my own resources, as well as those from my inheritance, to assist Dr. Greene and the Gladstone Institutes in the continued fight against HIV/AIDS.”

One Person’s Final Gift to Science Gets Us Closer to an HIV Cure

One Person’s Final Gift to Science Gets Us Closer to an HIV Cure

A new documentary follows Jim Dunn’s end-of-life decision to donate his tissues to HIV research.

Institutional News HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan LabBeyond Viruses: Expanding the Fight Against Infectious Diseases

Beyond Viruses: Expanding the Fight Against Infectious Diseases

The newly renamed Gladstone Infectious Disease Institute broadens its mission to address global health threats ranging from antibiotic resistance to infections that cause chronic diseases.

Institutional News News Release Cancer COVID-19 Hepatitis C HIV/AIDS Zika Virus Infectious DiseaseCharting the Body’s Defense Against HIV Leads to Broader Immune Revelations

Charting the Body’s Defense Against HIV Leads to Broader Immune Revelations

Gladstone scientists created a new tool to understand the immune system’s inner workings when confronted with a virus.

Research (Publication) HIV/AIDS Infectious Disease Roan Lab