Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

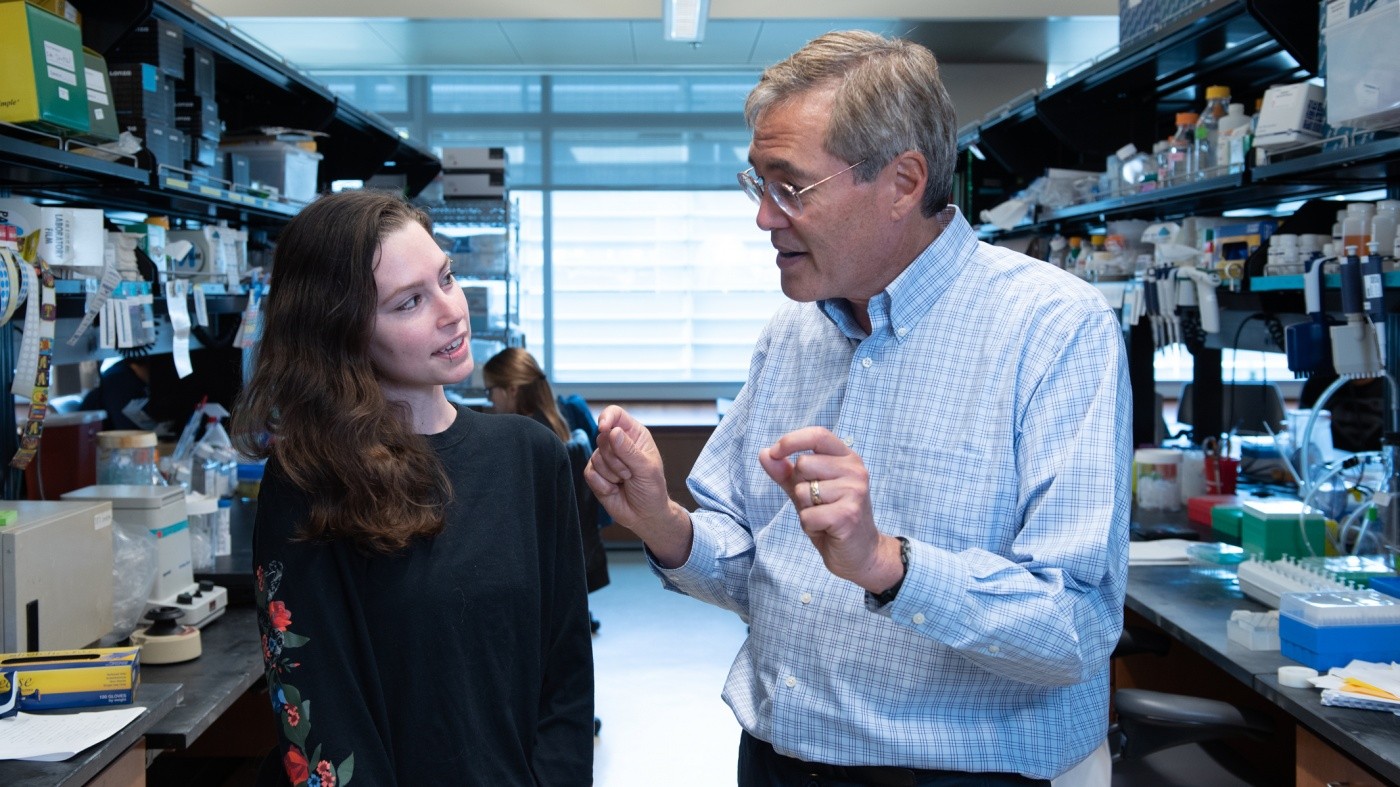

Delaney Van Riper (left) donated her blood cells for a research project led by Bruce Conklin (right) that may offer new hope for her genetic disorder.

Delaney Van Riper was diagnosed with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease at the age of 7. One of the most common inherited neurological disorders, it causes nerves to slowly degenerate and lose the ability to communicate with extremities—including feet, legs, and hands—often resulting in difficulty carrying out fine motor skills over time.

In 2017, Delaney began participating in a research project at Gladstone conducted by Senior Investigator Bruce Conklin, MD. Today, as a literature major at UC Santa Cruz, she was inspired to share her story and discuss the impact of her disorder on her life, as well as why she chose to take part in this study.

When you reveal you’re living with a genetic disorder, most people follow a polite script starting with, “How are you doing?”

In my nearly 13 years of living with defective motor nerves, there has never really been a sufficient answer to accurately explain, in those moments, the mix of frustration and acceptance I carry. So, a courteous, “I’m fine” and smile generally earn the expected, “That’s good.”

Then, the conversation either continues to how I live with it, what my limits are, how I’ve adapted, or it returns to a common relatable topic; both script courses have their benefits. For when I explain to an able-bodied person the day-to-day life of a disabled person, I enlighten them to the realities of the disabled. Yet, when they focus on another topic, I feel like I’m treated like a person rather than an oddity to stare and gawk at. I’ve grown accustomed to either script; it’s a fact of disabled life that no one really acknowledges.

However, recent advances in science have disrupted this script. There is a line, asked by the other party, it’s, “is there a cure?” This often occurs after they ask how I regulate the symptoms or if I mention my physical therapy. Previously I answered no. I’d state my acceptance of perpetual disability and comment on the perks of social pity.

Now, I mention that there is a genetic tool, CRISPR, being studied and explored in research groups as a possible remedy for genetic disabilities. In my interactions, this has opened a floodgate of questions that caused me to scramble for lines in the diverging script. Luckily, I’ve had the chance to fully mull over the benefits of editing my DNA with the research group I volunteer for at the Gladstone Institutes.

"The project at Gladstone offered me one of the most dangerously wonderful gifts: hope."

Near the end of my senior year in high school, I was forwarded a message by a genetic counselor asking for volunteers for a research project involving the use of CRISPR for gene editing. The project focused on disabilities and health complications caused by one strand of DNA having an incorrect code; the team of scientists led by Bruce Conklin hoped that by programming CRISPR to find the incorrect DNA section and remove it, the other healthy strand would be able to provide enough information to the cell to work properly.

If I participated, CRISPR would act as an editing tool to change the script written in my own DNA. And my disability, Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) Type 2 F, met the requirements for the study. CMT is a hereditary nerve disorder that causes the motor nerves to my feet and hands to fail, resulting in muscle loss and weakness within these areas of my body.

When I read the email, I wasn’t immediately filled with hope and elation as one might expect, but rather with surprised wonder that my disorder was a candidate. I had spent the last 11 years educating people on a rare disorder, their curiosity sparked by my unusual gait—even people in the medical field had often never heard of it. Yet, when this email entered my inbox and mentioned my disorder as one the researchers were looking into, I felt like I suddenly mattered.

I didn’t hesitate to accept. Sure, there were braces and wraps to correct my gait, and physical therapy exercises that decreased the severity of my symptoms, but that’s all damage control. I hadn’t previously seen any evidence that there was an investment in research to cure CMT. But now I know there is, and that I can contribute simply by donating blood cells.

Delaney Van Riper is currently a literature major at UC Santa Cruz

When I was invited to visit Bruce’s lab at Gladstone and saw the team of researchers treating my cells so carefully at their stations, and the intensity with which they worked, I understood that the health and happiness of others is important to them, and that they really are working toward a cure. I became closer to the process by being present and answering the team members’ questions, telling them how much of an impact their work would have. I acted as a bridge between patient and doctor, between the ideals of their goals and the reality of their actions, by showing them the person who produced the blood cells and who would receive their treatment.

I try not to run away with the hope I’ve gained from my glimpse into this world. I know from my parents’ gentle prompting and my own need for self-preservation that this research is not a promise of a cure. It only promises to test this technology as a possible cure. And even if it doesn’t work, I would know that my involvement would provide useful information for the progress of science. Yet, I can’t help but imagine the possibility that this could change my life.

For example, I had assumed that I would never venture into public speaking after passing my high school’s speech proficiency, but after my association with Gladstone became known to a high school teacher, I accepted her proposition to speak to her students in Biotech Academy. I accepted knowing that discussions of CRISPR were becoming more widespread, and I wished to be a source of information, hoping I would be a more amicable speaker as I’m near their age. During their class, I informed them of my involvement in the research group, my experience living with a disability, my knowledge of CRISPR, and answered any questions they had. This speech was a twist in my script; for the first time, I was bringing up my disability, rather than waiting to be asked about it.

Of course, I was scared, flooded with memories of teachers reminding me to speak clearly and slowly, to maintain eye contact while looking around the room, and to make sure I memorized my information. However, after the first few classes and awkward silences, speaking became easier. Combined with the responsiveness of the audience and the multiple classes I was speaking to, public speaking became easier. I quickly became eager to speak to the next class and eventually hoped to be asked to speak again next year, and maybe to other people. If it wasn’t for my connection to CRISPR, I don’t think I would have the confidence to be a guest speaker or become an advocate for researching genetic cures, as I realized that I will always carry this experience with me. I will always have a link to disability and to research groups, so what easier topic to discuss than one I’m intimately familiar with, one about my life?

I received generous praise and feedback after my presentations so I’m glad I could have such a positive effect, but my presence in the classroom was more than for inspiration. It was to inform people why research labs, funding for the sciences, and searches for cures are so important; why I joined the research group without hesitation, what these acts mean to the disabled.

I joined because the project at Gladstone offered me one of the most dangerously wonderful gifts: hope. Hope that I could be cured. Hope that I could live as a normal person. And if not hope for me, then hope for someone else. Hope that their disease or disorder is looked into, to know they are important. Hope that lives can be improved. Hope made me the editor of my own script.

Featured Experts

Support Discovery Science

Your gift to Gladstone will allow our researchers to pursue high-quality science, focus on disease, and train the next generation of scientific thought leaders.

Meet Gladstone: Alisa Dietl

Meet Gladstone: Alisa Dietl

Alisa Dietl brings her international training and clinical perspective to Gladstone, where she works to engineer more effective cancer immunotherapies for solid tumors.

Graduate Students and Postdocs Profile Cancer Pelka LabVoices of Outstanding Mentorship

Voices of Outstanding Mentorship

Three recipients of Gladstone’s Outstanding Mentoring Award share their personal approaches to mentorship and reflect how this passion has shaped their own growth as leaders.

Profile Roan Lab Graduate Students and PostdocsMeet Gladstone: Shyam Jinagal

Meet Gladstone: Shyam Jinagal

Shyam Jinagal explores how genetics, aging, and regeneration shape the heart—and how those insights could one day restore heart function after injury.

Graduate Students and Postdocs Profile Cardiovascular Disease Srivastava Lab