Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Lorenz Studer, winner of the 2017 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize. [Photo: Gladstone Institutes]

Lorenz P. Studer, MD, is the director of the Center for Stem Cell Biology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. As the winner of Gladstone’s 2017 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize, he was invited to San Francisco last month to present his groundbreaking research. The award recognizes over two decades of his work in stem cell biology. He discusses his upcoming clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease, his hopes for regenerative medicine, and his long partnership with his wife and fellow scientist.

Lorenz Studer is so close. In the next 6 months, he and his colleagues will finally start first-in-human clinical trials to help patients with Parkinson’s disease, the second most common neurodegenerative disease. But this comes after nearly 25 years of relentless hard work and steadfast determination.

Over the past two decades, he has been developing a revolutionary therapy that could restore movement for Parkinson’s patients. He is now waiting for the last few safety tests to be completed so he can obtain final FDA-approval. His goal is to transplant brain cells into 10 patients by the end of 2018.

“After so many years of thinking about the idea of using stem cells to help patients, it’s definitely exciting to finally be at the verge of actually doing it,” he said. “I’ve wanted to fulfill this dream for as long as I can remember, and I’ve been resolved to see it through to the end.”

Studer has been working on this idea since the 1990s. Although basic science has significantly advanced since then, he expresses disappointment that medicine hasn’t maintained a similar pace.

“If you read scientific journals, you find all these amazing breakthroughs every week,” he said. “The progress is amazing. Then, you go to the hospital and find patients without any good options, and you see that medical therapies haven’t really changed over the last 20 years. Many techniques are still the same, and many diseases remain without treatment. I struggle with this dichotomy between basic science and medicine. I think it’s important not to get overly excited by academia, but to actually try to deliver something meaningful to the patient. It’s what drives me.”

Studer is quite confident in his efforts—and the promise of regenerative medicine—as a way to provide long-term benefits to patients and replace current chronic treatments. He is hoping the success of the first clinical trials will show the cells are safe and well-tolerated, which will lead to scaling the technology to treat hundreds of people.

Despite his optimism, he remains cautious. “Obviously, that’s what we want for the future, but we need to take it one step at a time,” he said.

“Lorenz has already made great strides in his quest to translate his findings to the clinic,” said Deepak Srivastava, MD, director of the Roddenberry Stem Cell Center at the Gladstone Institutes, and member of the prize’s selection committee. “He was selected as the winner of the 2017 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize not only because he’s a very strong scientist, but due to his unwavering focus on helping patients. His tenacity, literally over decades, is most impressive.”

This Gladstone prize was established in 2015, through a generous gift from Hiro and Betty Ogawa, to support researchers conducting groundbreaking work in translational regenerative medicine. It is also named after Nobel laureate Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, in honor of his invention of induced pluripotent stem cells, which altered the landscape of stem cell biology worldwide.

“This prize honors what I’ve been working toward my entire scientific career,” said Studer. “I’m exceedingly proud to be the recipient of such a prestigious award.”

Lorenz Studer (right) receives the 2017 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize from Shinya Yamanaka (left) and Deepak Srivastava (center).

An Early Fascination with the Brain

Even as a child, growing up in a small village in Switzerland, Studer was always fascinated by the brain and its complexity. To him, it’s what makes us human. At 12 years old, he started reading Scientific American, a science and technology magazine aimed at college-educated readers.

He also had close family members with problems associated with the brain, including relatives who developed invasive brain tumors or psychiatric disorders.

“When you know someone so well and within 1 month they become a completely different person because of a brain tumor, it makes you realize how fragile the brain is,” he recalled. “I was astonished that personality could be so closely linked to an actual physical structure within the brain.”

When Studer started medical school in the late 1980s at the University of Bern, he thought he would become a neurologist, or maybe a neurosurgeon. Then, he came into contact with colleagues who were attempting a novel approach at the time—transplanting cells into the brain to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

“I found this to be a shocking idea; that you could take, in that case, fetal cells and inject them into an organ as complicated as the brain and expect them to make connections,” he said. “Simply the possibility that this could be done was unbelievable to me. I had so many questions. That’s when I became interested in basic research.”

Studer co-developed the first fetal stem cell–based therapy for Parkinson’s disease in Switzerland. The basic principle consists in replacing a type of nerve cells, called dopaminergic neurons, that are lost in the disease. These cells produce the important chemical known as dopamine. When they die, they cause the movement problems associated with Parkinson’s, like tremors, slowness of movement, and impaired balance.

However, working with fetal cells was cumbersome. He quickly understood that he would need to develop an alternative, sustainable source of dopamine-producing neurons if he ever hoped to treat the 10 million patients around the world suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

“Since that time, Lorenz has made a significant number of transformative contributions and developed protocols that have fundamentally changed the way we create stem cells in the lab,” said Lennart Mucke, MD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. “For instance, he published a landmark paper that outlined a reliable method to generate neurons from stem cells, which has been adopted by many investigators in the field.”

The Start of a Unique Partnership

In 1995, Studer began his postdoctoral fellowship in a large laboratory working on stem cells at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

This is when he met Viviane Tabar, MD, a stem cell biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering; the woman who would become his wife, and the mother of their two children. And the scientist and neurosurgeon who would work with him to develop the upcoming clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease.

They met during Tabar’s clinical training, when she joined the same lab at the NIH.

“I remember the first time I spoke to him, I saw a sparkle in his eye,” said Tabar. “I could really sense his passion for science, and noticed he was incredibly organized. So, I decided I wanted to work with him.”

At the time, the two trainees were trying to develop a therapy using stem cell–derived neurons in rat models. “We needed to monitor the animals’ behavior, and observe them for many, many hours, so we had a lot of time to talk!” remembered Studer. “We obviously enjoyed being together and I’m lucky to say this has continued throughout my life.”

“Support from your partner is crucial for anyone who wants to achieve success in a difficult career like this one,” said Yamanaka, Gladstone senior investigator. “Recognition of a scientist’s spouse was very important to Hiro and Betty Ogawa, my friends who created the stem cell prize at Gladstone.”

Tabar (left) and Studer (right).

Studer and Tabar are more than just spouses. The two have shared the vision of using regenerative medicine for Parkinson’s disease, and have worked on the project together for the past two decades.

“Young scientists often ask us questions about reconciling a career and family, and we always tell them that choosing the right partner is important,” said Tabar. “I think our partnership is unique, and an incredible privilege. It’s simply been great fun, and it will be amazing if we can help people.”

A Strenuous Journey to Clinical Trials

Studer, his wife, and their colleagues are on the cusp of human clinical trials. But the road to get to this point has been long and challenging.

Their approach to treat movement problems in Parkinson’s disease is based on replacing dopamine-producing neurons after they degenerate. The first step was determining how to obtain healthy samples of this specific type of cell.

The problem is that they are created in an 8-week-old embryo. And they’re meant to last for a person’s entire lifetime. This means no adult stem cell is capable of producing new ones.

“We needed to find a way to make millions of new cells in the lab, and then get them into the human brain,” said Studer. “It took us about 20 years to figure it out.”

They started by understanding how the embryo makes the neurons, and how to recreate those steps in a petri dish. Once this was accomplished, they noticed the cells didn’t function when transplanted into animal brains. The problem took nearly a decade to solve. The last hurdle was producing thousands of doses of the human stem cell–derived neurons in a standardized, FDA-approved facility, and getting them ready for trials.

“I’ve seen him go through ups and downs, like many scientists do,” noted Tabar. “But he’s very perseverant, and it’s difficult to discourage him. He never lost his passion. It’s even intensified over time.”

Tabar worked on developing the clinical protocol for how the cells will be given to patients. This will consist of injecting the neurons into specific areas of the patient’s brain with a small neurological procedure, much the like one used to perform routine biopsies.

Patients will then need to wait at least 6 months to see any benefit. The young neurons must mature and create millions of connections in the brain before they can become functional and start producing dopamine. Studer and his team expect this process to take 2 to 3 years to be fully completed.

“The amazing thing is that this should be a one-time treatment, which is quite unique,” said Studer. “Even if it’s slow at first, the hope with this regenerative approach is that the cells will last for the rest of that individual’s lifetime.”

Throughout this process, Studer and Tabar have worked with a multidisciplinary team of neurosurgeons, movement disorder neurologists, patient advocates, specialists in manufacturing cells, and ethicists.

“They found an excellent recipe to ensure the development of a successful therapy,” said Srivastava, who is also the incoming Gladstone president. “They complemented their scientific expertise by working closely with clinicians and advocates from the very early stages of the project, which provided a deeper understanding of how the disease impacts patients and how the treatment can best help them.”

“I’m incredibly thrilled to see the day come when we start the clinical trials, and to witness where we’ll go from there,” said Tabar. “I hope they will be successful and encourage more scientists and physicians to take a similar path in different aspects of medicine. It would be wonderful if we could contribute, even in a small way, to the dawn of regenerative medicine.”

A Promising Future

Since the beginning of his career, Studer has focused on major challenges in the field of stem cell research and tried to address bottlenecks. He has tackled the most challenging problems, and developed a series of techniques that have disrupted the field and enabled other scientists to push the limits of their own work.

“The protocols they developed for Parkinson’s disease are now being used, with some variations, all around the world,” said Yamanaka. “Thanks to work by Lorenz and others, we can now generate 50 different cell types, which could be used to develop new therapies or create powerful disease models. The potential is limitless.”

The next issue Studer will be tackling is how to control the age of stem cells. When you create them in a dish, they behave like fetal cells. To treat a disease like Parkinson’s, when you need young and resistant cells, this can be an asset. However, it can be difficult to use them to study a disease that happens only later in life, like Alzheimer’s disease. To overcome this obstacle, he is working to develop techniques that can trigger aging in the cells.

“It’s gratifying to enable a much larger effort than I could ever achieve in my own lab,” said Studer. “In my opinion, it’s pretty clear that the future lies in stem cells and regenerative medicine. I think we need all the brain power and willpower we can gather, and I’m encouraged when other scientists draw their attention to translating their findings to the clinic.”

Studer at the 2017 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize reception.

That might be easier said than done. Translational science requires determination. And it may not always be the most gratifying academically, particularly at times when you don’t publish many papers because you’re focused on pushing forward for a greater good.

“In addition to having trained as a physician, Lorenz is a meticulous and very rigorous scientist,” said Srivastava. “He’s the right kind of person to take the basic science and the translation seriously, and both aspects were needed to lead him to where he is today.”

“I think you have to be passionate about an idea you want to pursue,” said Studer. “That’s how it’s been for me, especially with the treatment for Parkinson’s disease. It’s a vision I had 20 years ago, and it was clear that I wanted to see it all the way through to the clinic. I didn’t want to complete part of it and pass it along. You never know if other people would have cared as much, or if they would have abandoned when they encountered all the hurdles we’ve faced. I wanted to give it my best shot, and I’m proud of how far we’ve gotten. But I’m not done yet!”

“Lorenz is an incredibly bright and passionate person, and I think he will achieve great things,” said Tabar. “He also inspires others. I’ve seen him motivate people to be much greater than they thought they could be, which is a remarkable quality, in a scientist and in a person.”

“I have huge expectations of him,” she said. “And I think he will exceed them. I really do.”

Support Discovery Science

Your gift to Gladstone will allow our researchers to pursue high-quality science, focus on disease, and train the next generation of scientific thought leaders.

A Sculptor of Modern Regenerative Medicine

A Sculptor of Modern Regenerative Medicine

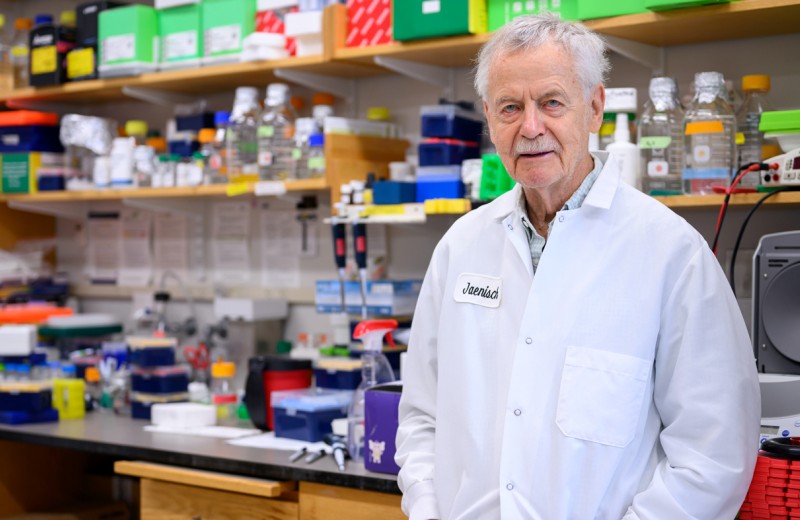

Among his myriad accomplishments, Rudolf Jaenisch—winner of the 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize—was the first to demonstrate the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells to treat disease.

Awards Ogawa Stem Cell Prize Profile Regenerative Medicine Stem Cells/iPSCsThe 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize Awarded to Rudolf Jaenisch

The 2025 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize Awarded to Rudolf Jaenisch

Jaenisch is recognized for his trailblazing contributions to epigenetics and stem cell biology, which have shaped modern regenerative medicine.

Awards News Release Ogawa Stem Cell Prize Stem Cells/iPSCs2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize Ceremony | Honoring Rusty Gage

2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize Ceremony | Honoring Rusty Gage

Rewatch the 2024 Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize Ceremony, honoring 2024 recipient Rusty Gage.

Ogawa Stem Cell Prize