Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

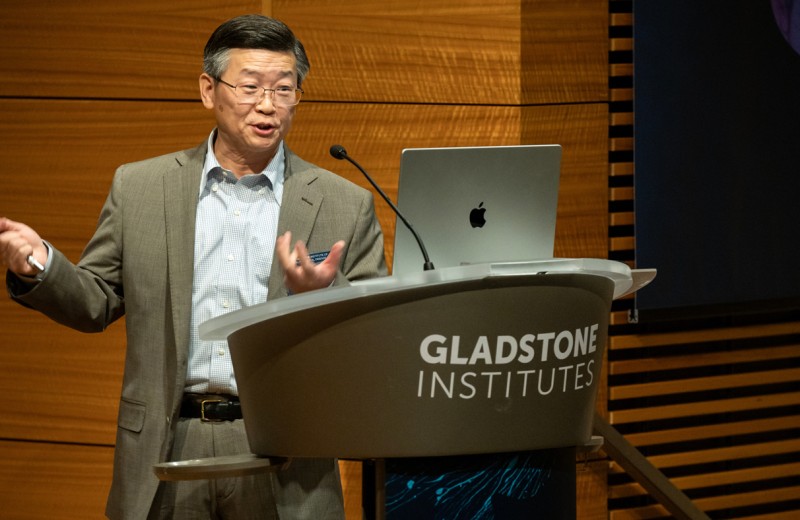

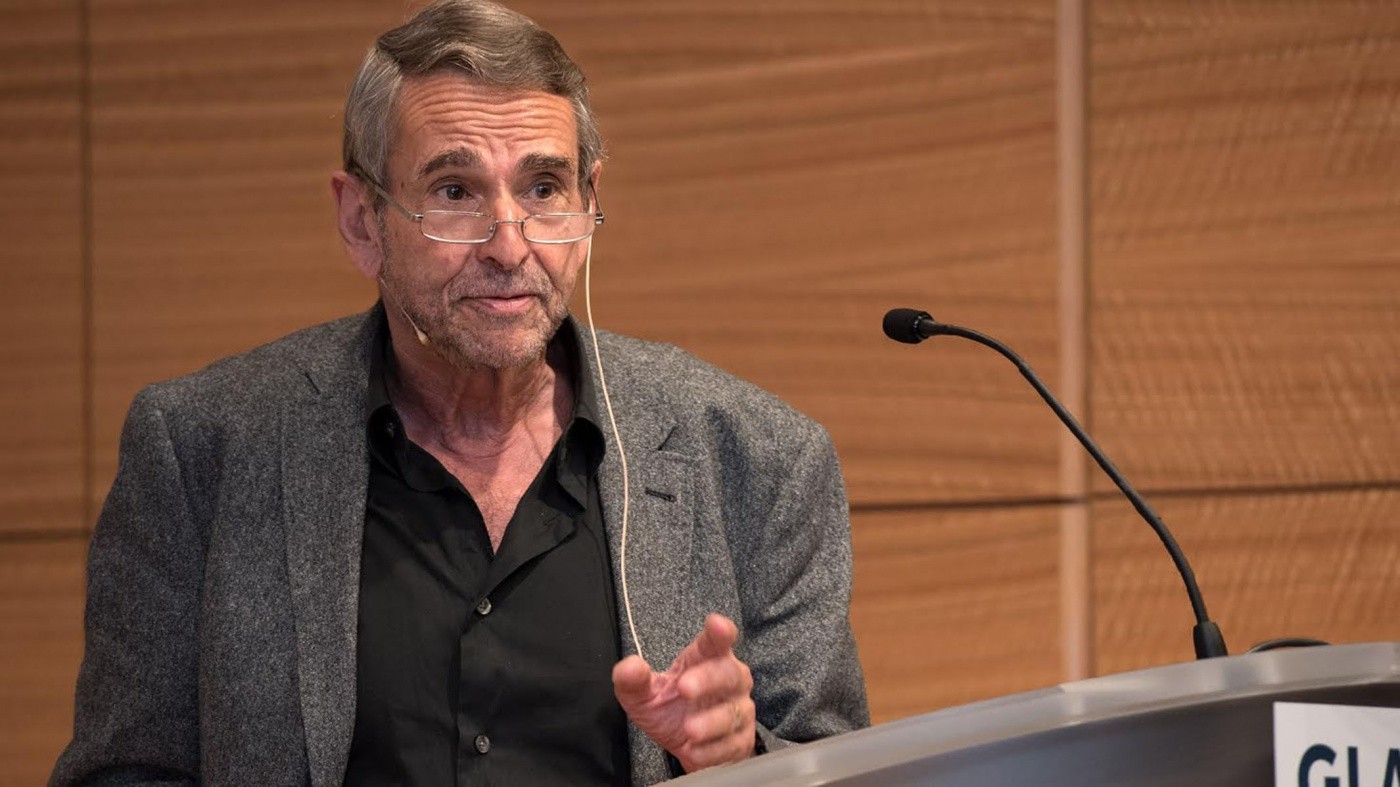

John Harris, PhD, spoke to the Gladstone community about ethical issues surrounding the quest for immortality. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow, Gladstone Institutes]

The Gladstone Institutes hosts special lectures intended to provoke critical dialogue and discussion among members of the Gladstone community. To this end, Gladstone invites speakers and experts from various disciplines to introduce new perspectives in the world of science.

On November 20, 2015, bioethicist and philosopher, John Harris, PhD, visited Gladstone, where he delivered a special lecture and posed a unique question: should scientists make immortality real?

For Harris, director of the Institute of Science, Ethics and Innovation at the University of Manchester, the answer can only be yes.

“The choice for human immortality would lead to the greater good of our scientists and population,” Harris said. “The evidence is strong that people want extra lifetime, even at the risk of pain and other probable costs.”

The quest for immortality has been a theme of human existence for millennia. Many writers and philosophers who also broached the subject of immortality throughout history, including Shakespeare, Goethe, Descartes, and Bulgakov explored the spiritual and philosophical implications associated with immortality.

Harris is known for his strong views on medical ethics, such as research on embryos, cloning, prenatal screening, and organ donation. He has served as an ethical consultant to several organizations, including the European Parliament, World Health Organization, and United Kingdom Department of Health.

Recently, Harris asserted that all biomedical scientists aim to extend the human lifespan, and that they have a moral duty to work toward this end, even if it means creating beings that live forever.

During his discussion at Gladstone, Harris detailed some of his reasons why scientists are morally obligated to extend the human lifespan, and he addressed many of the arguments against his position. For example, unless immortality is universal, one might wind up with “parallel populations” in which only the upper few could afford the treatments needed to extend lifespan. Harris believes that such treatments should be affordable for everyone, but he emphasizes that scientists may need to focus their efforts on an initial phase that permits access for only a few.

While many of Harris’ arguments have dramatic implications, his urging scientists to overcome ailments to human health echo the core mission of Gladstone. As a leader in biomedical research aimed at finding treatments for disease, Gladstone helps cultivate the global conversation about the impact of life-saving discoveries in healthcare.

Gladstone Presents Inaugural Sobrato Prize in Neuroscience to Yadong Huang, a Pioneer of Alzheimer’s Research

Gladstone Presents Inaugural Sobrato Prize in Neuroscience to Yadong Huang, a Pioneer of Alzheimer’s Research

The prize will be awarded annually to a Gladstone scientist who has made breakthrough discoveries in brain research; funds will help advance scientific discoveries from the lab to the clinic.

Awards News Release Alzheimer’s Disease Neurological Disease Huang Lab Aging Human GeneticsHope for Alzheimer’s: A Conversation with Gladstone’s Lennart Mucke

Hope for Alzheimer’s: A Conversation with Gladstone’s Lennart Mucke

Mucke, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease, discusses what’s next for Alzheimer’s research, the role of nonprofit research in developing new therapies, and why he’s more hopeful than ever for a future where neurodegenerative diseases are fully treatable—and even preventable.

Alzheimer’s Disease Neurological Disease Mucke Lab AgingRyan Corces Joins Gladstone Institutes

Ryan Corces Joins Gladstone Institutes

A new lab to study the impact of lived experiences on developing Alzheimer’s disease

Institutional News News Release Profile Alzheimer’s Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Neurological Disease Corces Lab Aging