Gladstone NOW: The Campaign Join Us on the Journey✕

Gladstone virologists answer questions from the community about the new Omicron variant and the current state of the pandemic.

As the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 continues to sweep through Europe and moves into the Middle East and Latin America, a new variant of Omicron, known as BA.2, is running up case counts in several nations. Denmark has been particularly hard hit with BA.2, which now accounts for over half of all infections in the country. In the United States, hospitalizations remain at high levels even as COVID-19 cases are declining in many of the communities that were hardest-hit by the virus earlier in the pandemic, allowing the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, to relax certain mandates.

Where is this pandemic taking us next?

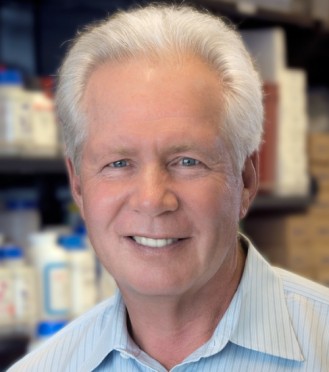

Virologists from Gladstone Institutes are closely monitoring the latest developments as they develop new ways to treat, prevent, and test for COVID-19. Three of these scientists—Warner Greene, MD, PhD, director of the Michael Hulton Center for HIV Cure Research; Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology, and Nadia Roan, PhD, associate investigator in the Gladstone Institute of Virology—recently took questions from the community about the new variant and the current state of the pandemic.

Some of these questions were also addressed live during an Ask the Experts webinar on January 31, 2022.

Is everybody really going to get Omicron, and if so, how does that affect the pandemic?

Roan: That everyone will eventually get exposed to Omicron is a definite possibility, as this variant and future highly-transmissible variants make their way around the world. We’ve all likely been previously exposed to the currently circulating common cold coronaviruses, and a similar situation may eventually occur with SARS-CoV-2 as it becomes endemic.

We’ve all heard that Omicron is milder, but one important thing to point out is that much of that may be attributed to prior immunity from vaccines or infection. Omicron is not considered “mild” in individuals with no prior immunity (e.g., unvaccinated individuals who were not previously infected), emphasizing the importance of upping our global vaccination efforts.

Ott: A big question is whether widespread infection by Omicron will result in a huge increase in immunity around the globe—and I think the answer is we don’t know yet. Initial studies have shown that the immune response after Omicron infection may be very narrow, and not protective against viral variants that look different than Omicron. However, we know that breakthrough infection in vaccinated people induces an incredibly broad and robust immune response that will be very effective in covering many variants that may come up in the future.

What is stealth Omicron?

Greene: The variant called stealth Omicron, officially known as BA.2, contains many of the same mutations as the original Omicron variant (BA.1), but with additional mutations primarily in the spike protein. Those additional mutations are probably making the variant more infectious, but it looks like the vaccines continue to be protective against serious disease. The stealth name came not because it spreads without being seen, but rather because it lacks the spike protein deletion that scientists initially used to quickly identify Omicron BA.1.

Omicron BA.2 is spreading worldwide and has been detected in 54 countries, including 24 states in the US. The original BA.1 variant, however, still accounts for 98 percent of Omicron infections. According to Denmark’s Serum Institute, BA.2 is probably one and a half times more infectious than BA.1.

How does protection differ between a prior infection and vaccination?

Ott: I consider a natural infection to be like one shot of a three-dose vaccine, and recovery from infection is probably not sufficient to produce long-lasting and broad immunity. Also, the immunity produced by natural infection depends on which variant was involved and, potentially, the severity of the infection.

Greene: Whether vaccination or natural infection confers a greater degree of protection remains controversial. Some studies from Europe suggest the vaccine provides a more effective and longer lasting form of protection. In contrast, recent studies published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that natural immunity is superior to vaccine-induced immunity. There is no argument, however, that natural infection and vaccination together induce a state of hybrid immunity, which conveys strong immunological protection. Of course, I prefer to be vaccinated and not naturally infected because of the potentially serious consequences of natural infections.

How much should we be worried about long COVID—the post-acute, long-term symptoms resulting from COVID-19—and how will Omicron affect that?

Roan: I think long COVID is a very big concern, and we still understand so little about it. The extent to which Omicron elicits long COVID is even less well understood, since Omicron hasn’t been around long enough. Studies are emerging that have identified immunological differences in recovered individuals with and without long COVID. The hope is that once we have a better understanding of what causes it, we can design targeted therapies to treat it. These are studies that we at Gladstone are currently doing in collaboration with researchers at UC San Francisco.

Ott: I would say it’s too early to know how Omicron will affect long COVID. We have good data now on the original virus, which was highly inflammatory. And we know there’s a high rate of people who reported symptoms past the original symptoms, in the post-acute phase. One hypothesis about long COVID is that it’s caused by people not completely clearing their initial infection, and harboring reservoirs of virus. If that’s the case, it will be important to learn how to get rid of these reservoirs, because they could be a source of new variants. The question of how we can best treat people with long COVID is a very important one. And that’s a big focus currently of the National Institutes of Health, and also for many of us here at Gladstone.

It’s also important to remember that experiencing long COVID doesn’t necessarily depend on how sick you were at the beginning of the infection. Many people who have had very low-level symptoms can also develop long COVID. And that’s why we have to be careful with Omicron, to make sure that we get to the bottom of this post-acute syndrome.

Greene: It does appear that vaccination reduces risks of long COVID. I’m concerned about the children though, who are getting infected in increasing numbers. Long COVID can certainly occur in them, as well as a multi-inflammatory syndrome in children, known as MIS-C. One positive thing about Omicron is that we are seeing fewer clotting problems than we did with earlier variants. If clotting has anything to do with long COVID, and there are many suggestions that it does, we could see less long COVID with Omicron.

Is it possible to contract the Omicron variant more than once?

Ott: Omicron is very immune evasive and people with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection can absolutely get reinfected with Omicron. We don’t yet know how long neutralizing immunity lasts after Omicron infection, but we know that in unvaccinated individuals, this immunity is not very robust. This means it is possible that after a certain time, the same person could be infected with Omicron more than once.

Greene: The simple answer is: we are not sure. Omicron is clearly quite efficient at reinfecting individuals who were previously infected with other variants, but whether Omicron can cause two consecutive infections is not clear. We simply don’t have enough experience with Omicron since it only appeared in late November and early December 2021. Its spread around the world at lightning speed has been remarkable.

In terms of the risk of a second infection, a lot could depend on the effectiveness of the initial immune response to Omicron. Since Omicron infections are generally mild in vaccinated individuals, the immune response might not be as robust, making people vulnerable to a second infection. Such second infections would likely occur approximately 3 months later, when immunity due to natural infection is known to wane.

Of course, prior vaccination could give a more prolonged response than natural infection, but the response might be more like the one elicited by the vaccines, which employ the original strain of virus and are perhaps not as protective against a second round of Omicron. Finally, we also need to consider a second infection caused by the BA.2 subvariant of Omicron. This subvariant is reported to be more infectious than BA.1 and carries even more mutations that can evade the immune system.

Overall, how likely are you to get reinfected if you already had COVID-19, whether Omicron or an earlier variant?

Roan: An unvaccinated person who previously had SARS-CoV-2 is less likely to get reinfected than someone who was never infected, but it can still happen. This was apparent during the Omicron wave in South Africa, where many individuals had immunity from prior infection. But this reinfection generally leads to mild disease, likely helped in part by the immunity that’s in place.

What’s the timeline of an Omicron infection?

Greene: The initial strain first identified in China had an incubation period—the time between exposure and the development of symptoms—of about 5 days. With the Delta variant, the incubation time dropped down to 4 days. Now, with Omicron, the incubation time has dropped even farther to an average of 3 days.

Once a person tests positive for Omicron, when will it be safe for them to be with others, even with a mask on?

Roan: Although there is a 5-day isolation recommendation from the CDC, there’s evidence that a substantial fraction of individuals may still be infectious after 5 days. And even after 10 days, about 10 percent may still harbor infectious virus. It’s hard to say exactly how long one will be infectious, as it varies from person to person, and based on whether the person was previously infected, vaccinated, and boosted.

Greene: A study from Japan shows that, with Omicron, people tend to shed the most virus—and therefore are most contagious—between 3 to 6 days after the onset of symptoms, with a sharp decline at 10 days. The United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency indicates that 31 percent of individuals infected with Omicron continue to have positive rapid antigen tests on day 5, and Harvard studies of the NBA show that 39 percent of infected players remain contagious on Day 5.

I think these data suggest strongly that we should be doing antigen testing on Day 5 before people reenter the work environment, because there’s a good chance they will be shedding at the 5-day mark, and thus should remain isolated.

How well are the existing vaccines protecting against COVID-19?

Greene: For people who are vaccinated and boosted, it’s estimated that the chances of dying each week from COVID-19 are basically one in a million. To put that in perspective, the chances of dying in a car accident every week are about 2.5 in a million. So indeed, vaccination and boosting offer very strong protection against death from COVID-19.

Should people get a fourth dose of the vaccine?

Greene: A fourth vaccine dose is clearly appropriate for severely immunocompromised individuals, who should also have preferential access to the drugs Paxlovid or Sotrovimab if they become infected. But for the majority of healthy younger adults, I don’t believe a fourth vaccine makes sense. Three doses provide strong protection from hospitalization and death, and these are the numbers that count, not the number of infections. That said, high-risk individuals—those more than 65 years old or with medical conditions—may benefit from an additional booster, although early data out of Israel suggest the benefit is small.

Ott: We have learned a lot from Israel regarding our strategies about the current vaccines. Israel has given a fourth shot, which raised the antibody levels, but did not make a huge difference in terms of overall infection rates. Since the three-shot vaccine has been so successful in reducing hospitalization and mortality, especially in the elderly, we will have to see if a fourth shot further improves these numbers. I personally believe that the vaccine will remain a three-shot vaccine, and may be complemented in the future with occasional variant-specific boosters.

What can we expect to happen next?

Ott: We are counting on a continuation of this sharp decline in the number of cases, and we hope it will go all the way down to very low numbers, and not stop somewhere halfway. The new Omicron BA.2 might give us a broader peak, but not necessarily another wave. And I think afterward, we will hopefully have a little calm, but we should be prepared to see some of these surges again in the future with new variants.

Greene: I’m very hopeful for the future. I think that within 3 to 6 months—assuming nothing bad happens with new variants—we’re going to be back in a fairly normal situation, particularly here in the San Francisco Bay Area because of the high vaccination and boosting rates. I think we’ll soon be able to put away our masks and engage with one another.

Globally, I suspect that intermittent outbreaks will occur within unvaccinated and uninfected individuals, and these will require interventions by local health authorities. Society will reopen, largely without masks or special precautions, especially for vaccinated and boosted individuals.

What could upset our return to a relatively normal life is the emergence of a variant of high consequence that eludes the protection afforded by our vaccines. We’ve not seen such a variant yet, but, of course, this virus continues to evolve and we don’t know from which direction the next variant will come at us.

Support Our COVID-19 Research Efforts

Gladstone scientists are moving quickly to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. Help us end this pandemic.

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

Gladstone’s Scientific Highlights of 2025

From fundamental insights to translational advances, here’s how Gladstone researchers moved science forward in 2025.

Gladstone Experts Alzheimer’s Disease Autoimmune Diseases COVID-19 Neurological Disease Genomic Immunology Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Infectious Disease Conklin LabScience in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Science in Seconds | Researchers Pinpoint Key Gene Behind Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

In this video, Gladstone scientists share how they used stem cells, gene editing, and AI to identify a gene driving heart defects in Down syndrome—and how reducing its levels in mice restored normal heart development, offering hope for future treatments

Gladstone Experts Cardiovascular Disease Data Science and Biotechnology Pollard Lab Srivastava Lab AI Big Data CRISPR/Gene Editing Human Genetics Stem Cells/iPSCsScience in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

Science in Seconds | The Thinking Microscope: Research Powered by an AI Brain

In this video, Steve Finkbeiner and Jeremy Linsley showcase Gladstone’s groundbreaking “thinking microscope”—an AI-powered system that can design, conduct, and analyze experiments autonomously to uncover new insights into diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS.

Gladstone Experts ALS Alzheimer’s Disease Parkinson’s Disease Neurological Disease Finkbeiner Lab AI Big Data