For more than 40 years, Gladstone Institutes has been driving transformative biomedical discovery across high-need disease areas. An independent, nonprofit research organization based in San Francisco, Gladstone builds on a history of bold decision-making to follow the science where it leads, always with the patient in mind. Gladstone’s achievements of the past are the foundation of our future—a future in which it’s possible, for the first time, to contemplate cures.

1970s: A Generous Founder and Visionary Trustees

1990s: Gladstone Expands Its Impact

2000s: A Bold Move to Mission Bay

2018–Present: Pioneers in a Golden Age of Science

J. David Gladstone, right, a pioneering real estate developer, marks the opening of a store at a shopping center he built in Fontana, California, in the late 1950s. His estate provided the financial resources to establish Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco.

1970s: A Generous Founder and Visionary Trustees

J. David Gladstone, a pioneering developer of shopping centers, left an estate valued at $8 million when he passed away unexpectedly in 1971. In his trust, he designated that the funds provide scholarships for medical students interested in blood and vascular disease research. Those funds, however, were tied up in the ambitious and unfinished Northridge Fashion Center, a regional shopping mall he was developing in southern California.

J.David Gladstone

The estate’s three trustees—Richard Brawerman, Richard Jones, and David Orgell—made the bold decision to finish the shopping center. But they also saw an opportunity to grow the value of the trust and expand on J. David Gladstone’s vision. Thanks to a dramatic appreciation in real estate values, they found themselves with enough funds to impact scientific research beyond student scholarships; they had the financial basis to create a world-class medical research organization.

With court approval, the estate established Gladstone Laboratories in 1979. The entity would have an academic affiliation with UC San Francisco (UCSF) but remain administratively independent, free to pursue any avenue of research and apply discoveries to better the human condition—basic science with a purpose. In accordance with J. David Gladstone’s wishes, the new nonprofit organization would focus on cardiovascular disease research, and Robert Mahley, MD, PhD, then a 37-year-old biochemist studying the role of cholesterol in heart disease, was recruited from the National Institutes of Health to lead it.

At 37 years old, Robert Mahley, MD, PhD, left his job at the NIH and moved across the country to lay the foundation for Gladstone Institutes. In this photo, Mahley (right) stands with Karl H. Weisgraber, PhD (left), one of the scientists who moved to San Francisco to help launch Gladstone.

1980s: The Early Years

The new Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease was headquartered at San Francisco General Hospital. Lab space wasn’t available at first, so Mahley and his team borrowed a conference room and set up a card table as a desk. He’d brought his small but diverse research group from the NIH: an organic chemist, a cell biologist, a protein chemist, a lipid biochemist, a clinician, and a research associate. Assembling teams of investigators from different disciplines to tackle emerging health problems would become the blueprint for Gladstone’s future successes.

Once lab space became available, Mahley and his team continued to investigate cholesterol metabolism. Their findings contributed to a field that received global attention in 1985 when the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein “for their discoveries concerning the regulation of cholesterol metabolism.” Brown and Goldstein joined Gladstone’s scientific advisory board, and Goldstein is still a member today.

Among its many key findings, Mahley’s lab determined the structure and function of a protein called apolipoprotein E, which is involved in the metabolism of fats, and its three forms in humans: APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4.

The trustees sold the Northridge shopping center and another one in Bakersfield, increasing Gladstone’s trust to more than $120 million. With those resources at hand, they pondered expanding into other biomedical research areas.

An immediate opportunity emerged just outside Gladstone’s walls.

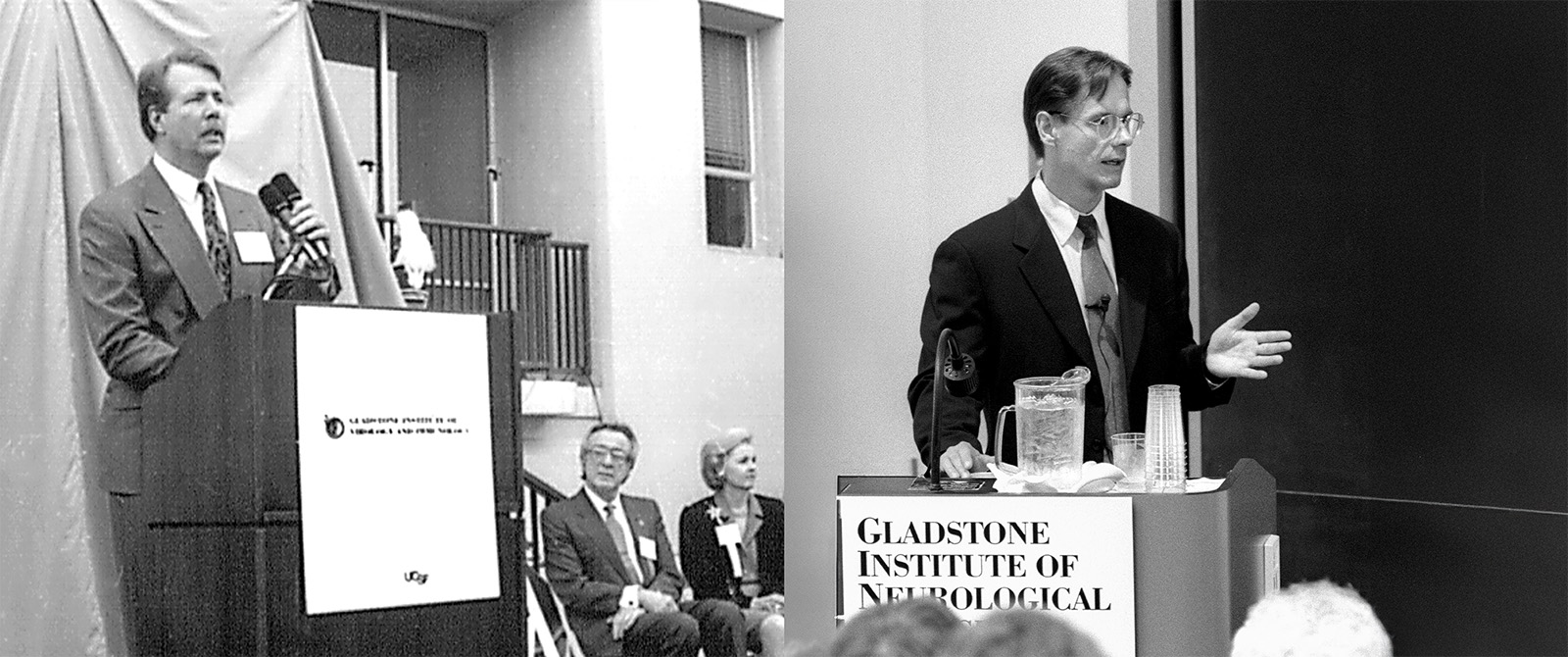

Left: In 1992, Warner Greene, MD, PhD, was named founding director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology. Initially established to help confront the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the institute now studies a range of viruses that impact human health. Right: Lennart Mucke, PhD, was appointed founding director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease in 1998. Today, diverse research teams seek to better understand, prevent, and develop treatments for the devastating diseases that affect the central nervous system.

1990s: Gladstone Expands Its Impact

The HIV/AIDS epidemic had been declared a global health crisis by the 1980s and San Francisco was its epicenter. Given that Mahley was already working with UCSF to develop plans for an HIV/AIDS research center, he and the trustees decided that Gladstone was well-positioned to take on this deadly virus. In 1992, the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology was established, and Warner Greene, MD, PhD, a molecular biologist who had been leading HIV research at Duke University, was brought on as the institute’s director.

Greene’s team of researchers began solving some of the disease’s mysteries. They showed how CD4 T-cells, a type of immune cell, die during HIV infection. Later, a team co-led by Robert Grant, MD, MPH, conducted the first pivotal trial, across 19 countries, that proved antiretroviral drugs could prevent high-risk individuals from becoming infected. This work led to FDA approval of the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PReP) drug Truvada in 2014.

During the 1990s, Mahley also made the surprising discovery that APOE, in addition to its role in heart disease, is produced in large concentrations in the brain. Human genetics also demonstrated that a variant in the APOE gene, APOE4, was highly linked to Alzheimer’s disease. The finding steered his research interest toward the role of APOE4 in Alzheimer’s disease and established Gladstone as a leading knowledge center for this protein. In 1998, the decision was made to create a third institute, the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. Lennart Mucke, MD, a neuroscientist who had been recruited to the Bay Area from Scripps Research two years earlier, was named the director.

Mucke’s team revealed that certain variations in the APOE4 gene cause amyloid proteins to accumulate, forming the plaques in the brain that are associated with Alzheimer’s

In collaboration with Mahley, Mucke’s team revealed that the APOE4 gene causes amyloid proteins to accumulate, forming the plaques in the brain that are associated with Alzheimer’s. But they also showed that other versions of APOE prevent amyloid plaques, suggesting that altering APOE could be pivotal in disease and for therapies. They pursued research into this and other complex neurodegenerative disorders with multipronged investigational and therapeutics approaches, enhancing Gladstone’s reputation for outside-the-box research.

By the late 1990s, Gladstone encompassed three institutes operating out of three different San Francisco General Hospital buildings. The scientists were not only running out of space, they were missing out on opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaboration.

In 2004, Gladstone completed construction of a six-story, 200,000-square-foot biomedical research building in the Mission Bay area of San Francisco, allowing its expanding company of researchers and staff to pursue scientific collaborations under one roof.

2000s: A Bold Move to Mission Bay

Gladstone’s trustees and leadership united in another bold decision: relocate the research organization to San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood, which was, at the time, a largely undeveloped wasteland of warehouses, parking lots, and railroad yards. UCSF had plans to build a large campus at Mission Bay, and its first building opened in 2003.

The trustees commissioned architectural plans and secured a multimillion-dollar bond to finance construction, which began in early 2003. The six-story building, encompassing approximately 200,000 square feet, was completed ahead of schedule and under budget. Gladstone Institutes moved into its new headquarters the following year, marking its 25th anniversary. Scientists were finally able to work in close proximity, fostering the collaborative culture that continues to characterize Gladstone today.

By this time, Mahley had decided that the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease should broaden its research scope. In 2005, he recruited Deepak Srivastava, MD, to lead the expanded institute. Srivastava, then at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, was conducting cutting-edge research on gene networks that guide heart development.

Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD

Gladstone also brought on other world-class scientists around this time—notably, stem cell pioneer Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, a Gladstone postdoctoral scholar in the ’90s who Srivastava recruited as a senior investigator in 2007. Yamanaka subsequently won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent stem cells, meaning they could be induced to develop into nearly any type of cell in the body.

During Mahley’s remarkable 30-year tenure, he grew a fledgling research enterprise from seven people and a budget of $500,000 in 1979 into a robust organization of approximately 400 people and a budget of $65 million in 2010. He stepped down from the presidency in 2010 to more actively pursue his own research at Gladstone.

The Gladstone Foundation’s board members, who provide financial and advisory support to Gladstone, meet regularly with the leadership team and institute directors. In this photo, board members meet with Alex Marson, Jennifer Doudna, and Deepak Srivastava during the 2022 meeting.

2010s: Passing the Torch

Gladstone’s trustees tapped R. Sanders Williams, MD, from his position as dean of the School of Medicine at Duke University to become the second president of Gladstone Institutes.

R.Sanders Williams, MD

Williams inherited a vibrant research organization—but one that, like many of its peers, was facing financial pressures. The global economy was still reeling from the Great Recession, earnings on the trust’s investments had suffered, and NIH grants were harder to come by. With experience serving on multiple advisory boards for life science companies, Williams understood the changing landscape and set about establishing a new business model at Gladstone.

Williams fostered relationships between Gladstone and venture capitalists, as well as biotech and pharmaceutical companies, some of which led to partnerships or spinoff companies

Gladstone’s aim had always been “science with a purpose,” and Williams took steps to further serve that purpose, setting up the infrastructure that could move laboratory discoveries closer to patients. He fostered relationships between Gladstone and venture capitalists, as well as biotech and pharmaceutical companies, some of which led to partnerships or spinoff companies.

In 2015, he established BioFulcrum, an entrepreneurial program designed to advance Gladstone’s disease-related breakthroughs toward clinical trials via a network of scientists, nonprofit organizations, and industry partners. Tenaya Therapeutics, a now-publicly-traded biotechnology company focused on regenerative medicine for heart failure, emerged from this initiative in 2016 based on discoveries from a team of labs in the cardiovascular institute. A second program, BioFulcrum 2.0, aimed at developing new classes of antiviral and antibacterial therapeutics, launched the following year.

To diversify revenue sources even further, Williams increased Gladstone’s emphasis on philanthropy. He helped create the Gladstone Foundation, whose board members—leaders from an array of industries—provide financial and advisory support to Gladstone Institutes.

By the end of 2017, Gladstone was once again on strong footing. Williams, having developed a succession plan, left the presidency to return to Duke University. He remains a trusted advisor to Gladstone and continues to serve on the board of directors for the Gladstone Foundation.

Katie Pollard, PhD, was named founding director of the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology in 2018. The institute’s engineers, mathematicians, and biologists help gather and analyze massive amounts of data, and ultimately identify new ways to treat disease.

2018–Present: Pioneers in a Golden Age of Science

Deepak Srivastava, MD

The trustees selected Srivastava, director of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease since 2005, to become the third president of Gladstone Institutes. After an international search, gene regulation expert Benoit Bruneau, PhD, who was recruited to Gladstone from the University of Toronto in 2006, was selected to direct the cardiovascular disease institute. Srivastava moved into the president’s office in January 2018.

Keenly aware that scientific research was increasingly data-intensive and technology-driven, Srivastava began developing a strategy to ensure Gladstone remained fully equipped to pioneer biomedical discovery. He established a fourth institute, the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology, naming Katie Pollard, PhD, to direct it. The institute’s groundbreaking work in computational biology, artificial intelligence, and genomics is leading to a better understanding of the root causes of disease and how to address them.

Jennifer Doudna, PhD

That same year, Srivastava recruited biochemist Jennifer Doudna, PhD, to Gladstone. Doudna would go on to share the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for inventing CRISPR-Cas9, a revolutionary method for genome editing. Now, with Nobel laureates Yamanaka and Doudna overseeing laboratories under its roof, Gladstone could rightfully claim leadership in two of the era’s most transformative technologies.

Marson and his colleagues are genetically modifying cells to create “living medicines” that can fight cancer, infectious disease, and autoimmune diseases

In 2020, Srivastava oversaw the establishment of a fifth institute, and the first joint institute with UCSF, the Gladstone-UCSF Institute of Genomic Immunology. Directed by Alexander Marson, MD, PhD, this institute unites experts in immunology, synthetic biology, human genetics, and CRISPR genome editing with experts in manufacturing and clinical trial design. Marson and his colleagues are genetically modifying cells to create “living medicines” that can fight cancer, infectious disease, and autoimmune diseases.

Alex Marson, MD, PhD

Concurrent with the founding of this fifth institute, Gladstone’s second-oldest institute was renamed the Gladstone Institute of Virology, and Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, a noted virologist who already had a lab at Gladstone, was named director. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists in this institute rapidly pivoted their research focus to the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Their discoveries have vastly expanded scientific understanding of numerous deadly viruses and are helping prepare for future pandemic threats.

Gladstone also joins forces with game-changing groups such as the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Network and Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy

In 2023, Gladstone Institutes announced plans to expand its laboratory space by nearly 50 percent and to add hundreds of new scientists. It continues to advance its breakthrough discoveries closer to patients, with more than 15 spinoff companies created between 2013 and 2023. New affiliations with UC Berkeley and Stanford University augment the longstanding affiliation with UC San Francisco, and Gladstone also joined forces with game-changing groups such as the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco and Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

J. David Gladstone’s initial planned gift of $8 million to fund student scholarships has been thoughtfully managed over the years, evolving into total assets of more than $400 million, despite having spent over $400 million on science over the years. Today, Gladstone Institutes is a thriving and highly respected biomedical research organization that brings together the best minds to focus on one goal—science overcoming disease—and realize one man’s dream of helping humankind.

Left: Benoit Bruneau, PhD, is the director of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, where researchers are working to tackle one of the world’s leading causes of death. Right: Melanie Ott, MD, PhD, serves as director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology, where researchers are generating rapid diagnostics, innovative vaccines, and new drugs against dangerous viral infections.