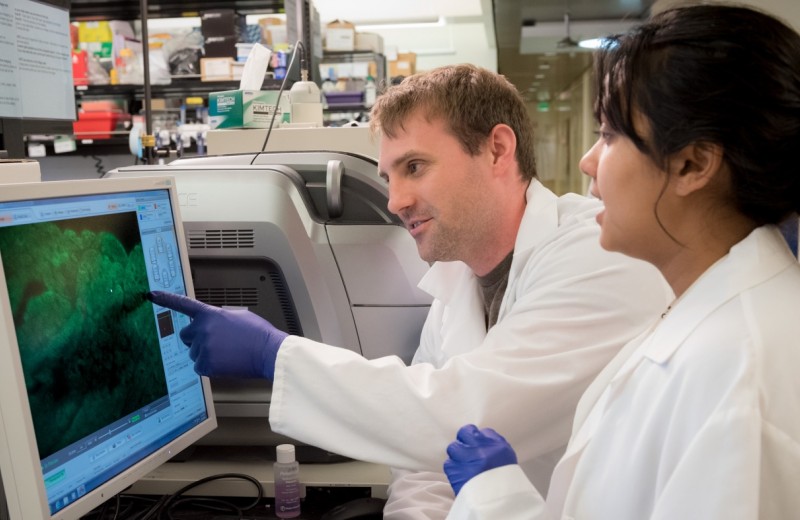

Emily Jones (right) with her mentee, Hena Khairzadah. Aided by a series of Gladstone workshops, Jones says she learned valuable lessons in her evolution from mentee to mentor. [Photo: Chris Goodfellow, Gladstone Institutes]

Good mentoring is a critical part of all good science. Like many of us, I received guidance from several mentors in the past, so I thought I was equipped with the skills to take on the task myself. I quickly learned that being a mentor comes with its own unique challenges and demands.

My first adventure in mentoring took place last summer when my supervisor, Yadong Huang, MD, PhD, a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institutes, paired me with two high school interns, Alyssa Yang and Hanci Lei. Fortunately, Shannon Noonan, MS, education and community partnerships manager, and Sudha Krishnamurthy, PhD, program director for the Office of Postdoctoral and Graduate Affairs, created a mentoring workshop series at Gladstone that summer to help guide new mentors like me. Each workshop taught me a new set of skills I did not realize I needed and greatly helped me develop and grow as a mentor.

Set Limits

The “Defining Boundaries” workshop was particularly relevant given my age. As a young graduate student starting my third year, I am often close in age to my mentees, and I found that my mentees sought friendship from me. Through this workshop, I learned the importance of keeping a professional distance and giving my mentees space, so that they could learn to give me space in return and respect my role as their mentor. While it can be difficult to say “no” to offers of friendship from your mentee, setting limits makes the relationship healthier in the long run.

Appreciate Differences

The “Respecting Others’ Differences” workshop became especially useful this year, when I took on a community college intern, Hena Khairzadah, as part of Gladstone’s Promoting Underrepresented Minorities Advancing in the Sciences (PUMAS) program. I quickly learned that you must consider the unique background of each person you mentor. While this can require some additional planning, it also offers a new set of lessons and rewards. This workshop helped me to identify when differences between my mentee and me were simply variations in working or learning styles and when they were opportunities to help my mentee—or myself—improve. It also reminded me to put myself in my mentee’s shoes and to see the lab from her perspective, working in science for the first time, just as I did during my first internship seven years ago.

Communicate Clearly

The “Having Difficult Conversations” workshop will likely be beneficial for my entire scientific career. Like many, I have never been comfortable with confrontation, which has led to missed opportunities to improve my working relationships. After this workshop, I began to notice when my expectations for a project differed from my mentees or collaborators, and because of the tools I learned, I practiced ways to communicate my perspectives more clearly. I also became more confident in giving and receiving critical feedback. However, the most significant lesson that I learned from this session was the importance of choosing your battles wisely.

Developing Philosophy and Style

Mentoring is an essential skill for scientists to develop, but it often receives little attention or formal training. The workshops at Gladstone help to fill that gap.

Beyond specific skills, these workshops helped me develop my mentoring philosophy: mentoring should be mutually beneficial and provide valuable lessons. My aim is to expose my mentee to as much of the life of a scientist as I can in one summer. Moreover, I want to help shape their internship based on their needs and career goals, not the demands of my own projects. During our time together, I help build their independence incrementally, starting with teaching them how to read an original research article and understand the science behind experiments, and ultimately working toward the final goal of designing their own research questions, interpreting their results, and defending their ideas in front of other scientists.

My mentoring style has also greatly matured over time with the help of these workshops. At the start, I did not know how much structure was needed and the amount of behind-the-scenes planning that occurs to guide a mentee through the incredible amount of learning one summer can encompass. Now, I follow a week-by-week checklist of all the milestones I want my mentee to reach. I see projects as opportunities to make mistakes and learn from them, and I frame miscommunication as a way to adapt my teaching style to fit the needs of my mentee.

The most valuable part of my mentoring experience, though, has been watching my mentees progress beyond what I originally thought possible. Hena gained confidence and mastered the finesse of loading a gel, Hanci presented in a journal club after having read a scientific paper for the first time just a few weeks prior, and Alyssa successfully explained a difficult concept she had struggled with all summer in a lab meeting.

Lessons as a Mentee

Through my own mentors over the years, I have learned to stand behind the things I know, to admit the things I don’t, and to appreciate that all ideas—including my own—are worthwhile. My mentors have pushed me to make good science even better, to appreciate my work as important, and to slowly inch towards independence. I look up to my mentors, and I hope to one day be able to mentor as well as they have guided me.

A Career in Service: from the Military to Medicine

A Career in Service: from the Military to Medicine

Inspired by his time in the National Guard, Gladstone summer intern pursues career in science and medicine.

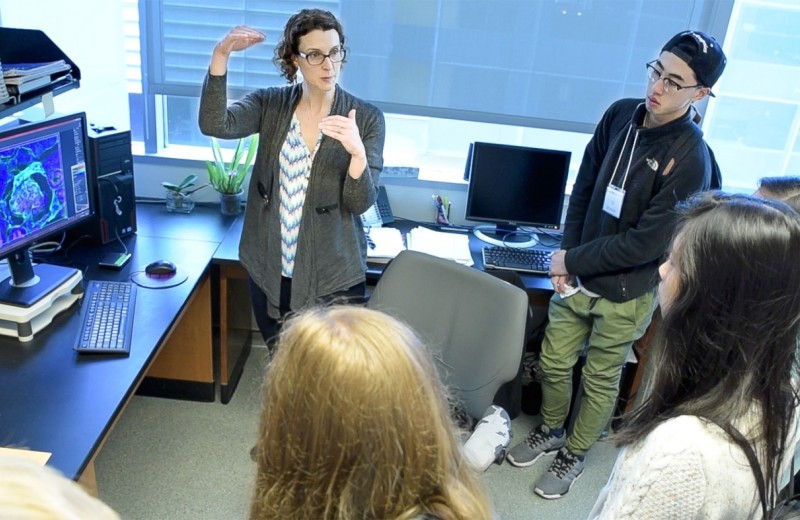

Srivastava Lab OutreachSchools in the Bay Area Take Part in Fifth Annual Gladstone Open House

Schools in the Bay Area Take Part in Fifth Annual Gladstone Open House

At the Gladstone Institutes, inspiring and educating the next generation of scientists is a top priority, for when researchers share their knowledge with young minds, they contribute to a legacy that will help shape the future of scientific innovation.

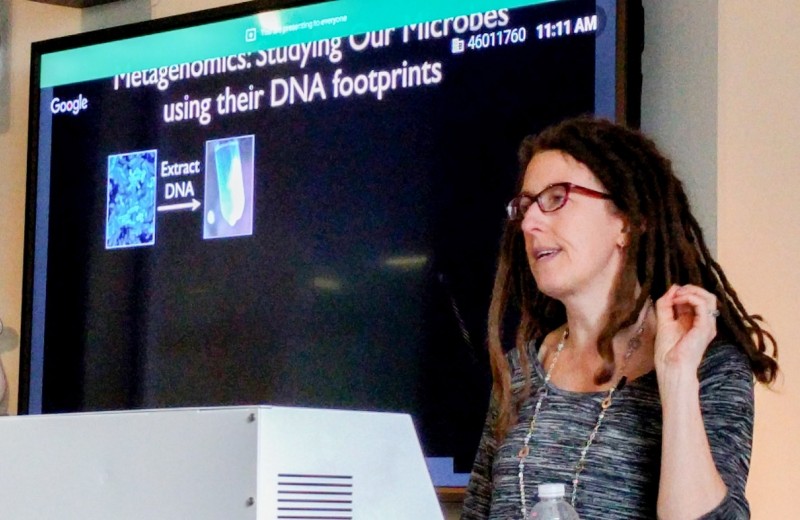

OutreachKatherine Pollard Presents at Google in Gladstone’s New Series of Open Classroom Talks

Katherine Pollard Presents at Google in Gladstone’s New Series of Open Classroom Talks

Katherine Pollard shares science on big data and high-performance computing with an audience at Google as part of the Gladstone Open Classroom Talks series.

Pollard Lab Microbiome Outreach